Alice Vigani

2nd year ERI student, majoring in Social Psychology:

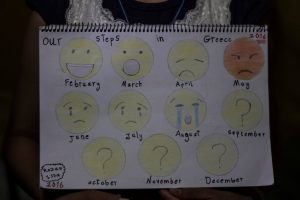

60 000. That is the number of asylum seekers stranded in Greece, according to recent estimates. Greece has been, together with Italy, the main country of first arrival in Europe since the start of the so-called refugee crisis. It has been a transit country, where only few decided to stop, but when the Balkan borders closed earlier this year, the flow of people leaving the country dropped while new arrivals did not stop. At the same time, the Relocation Program from one member state to another did not reflect initial expectations: the application process is extremely long, with people waiting several months just to get their first interview, and while accommodation in reception centers, hotels or apartments should be provided during the waiting period, this declaration on paper rarely turned into practice. Moreover, the possibility to apply is limited to people of certain nationalities, excluding for example Iraqis (since July 2016) and Afghans. Over all, a very small percentage of people have seen their application go through successfully until now.

The result? Thousands find themselves stuck for months in official and unofficial camps, as well as detention centres or even on the street, both on the islands and in the mainland.

This summer I spent two months in Athens to see the situation for myself. I have been an independent volunteer, that means that I was not affiliated with any group or NGO. This choice proved difficult at times, as in comparison with previous volunteering experiences I lacked the social support and directions deriving from working with a group. On the other hand, it has provided me the chance to visit a number of centers and camps characterized by very different living conditions and organisation: from day centers providing services such as food, clothing, legal and psychological support to hundreds a day like the Caritas Hellas day center in Omonia, to official and unofficial camps like the now dismantled informal one at the harbour of Pireus, the naval base of Skaramangas and Elliniko (on the premises of the old airport of the city as well as the baseball and hockey stadiums for the 2004 olympic games). Organisations and the government struggle to manage the existing structures and accommodation areas: camps filled well over their capacity, often lacking basic services and decent living conditions, put another toll on residents who feel trapped in a grim present and filled with uncertainty about the future.

Therefore, some local collectives and refugees took action to find alternative models of collaboration and coexistence. One example is the ex Hotel City Plaza, once three star hotel close to Victoria Square, now home to 400 refugees, of which almost half are minors. Hotel City Plaza is only one of the many squats present in the city. There, people have found a place where they can live with dignity while actively contributing to shape the project: all duties, as well as decisions, are shared among the residents, with the support of volunteers, activists and donations from all over the world. Day to day, turns to cook and clean are organised, along with a variety of activities including language courses, legal advice, kids’ educational and recreational activities. I took part in the latter, and I couldn’t help but feel proud hearing that most of the children and adolescents I met excitedly started attending local schools this September, thanks to the support of their families and volunteers.

Looking back at my summer in Athens, I feel lucky and enriched by this experience. The tools and knowledge acquired through the ERI master programme helped me countless times to approach difficult situations, but now I can also see how much these two months have given me in return.

Even if I already considered myself an open-minded person, it took me some time to work on my own assumptions and preconceptions. Only when I stopped seeing “refugees” in front of me and started seeing individuals instead I was really able to bring my own, small contribution. I also had to put aside my own expectations concerning what was needed and how to act. While food, accommodation and health remain imprescindible concerns, the people I met needed and wanted much more: to know their relatives are safe, to be listened, to put to use their competences, to learn. I felt embarrassed to find myself surprised when some refugees decided to organise a support group for LGBT people.

Meeting people who contradicted the sterile narratives of refugees as victims to be pitied or as heroes to be admired is what did the trick for me. The 20-year-old girl graduating in mechanical engineers, the woman fighting for gender equality while making carpets in her tent, the 4-year-old and his family who never told me a word but made me understand the value of a hug, the passionate man who never stops working to help others only to go back to sleep in his container at the end of the day. But also the violent, loud bully who steals from those who can’t defend themselves, the petulant woman who gossiped about others over and over, the ones who manifested their frustration through violence putting at risk the ones around them. Some I liked, others I did not, as it happens with anyone, and that did not take away anything from my understanding and solidarity to the refugee cause, only strengthened it: being in the position to listen to each story as unique and personal allowed me to get a better grasp of the bigger picture while trying to escape generalisations, always too easy to fall into.

I have learned a lot also from other volunteers and activists. I have seen inspirational people dedicate all of their knowledge, time and energy, but also too many “voluntourists”, attracted by the media attention on the topic and stopping by for a few days without respecting the work of others. I have had the luck to work side by side for a few days with two wonderful women from the States who, years ago, were themselves in the same position of the ones that they were helping. I have seen a young volunteer instruct them for half an hour concerning Muslim women, while they politely smiled from behind their hijabs. I have seen volunteers and activists putting their own political or religious agenda before the well-being of the people they were claiming to help: from collectives too focused on advancing within the anarchist scene in Athens to guarantee proper conditions in their squats, to bibles being distributed to Muslims during Ramadan.

I have met people who helped me give a new meaning to solidarity, like the man who, after a long day at work, spends hours everyday bringing food, water and some company to people in the streets, finding shelter to many. But I have also seen solidarity in simple day-to-day acts, from the bakery-owner saving a few croissants every day for the Syrian family who visit him from the camp nearby, to the stranger buying metro tickets to a mum and her child. For most of my stay, I did not see striking episodes of racism or discrimination, but towards the end of the summer the situation became more tense, with more and more demonstrations organised by nationalist groups, arriving to the point of an arson attack to Notara squat, where tens of refugees, including families, were sleeping. Luckily the fire did not provoke fatalities, but a lot of damages to the property, quickly repaired by residents and volunteers come together from all over the city.

I have learned as a social scientist too, because whenever I will fill my mouth and my mind with issues and fancy terms, they will hold a richer meaning as I won’t be able to detach them from the face of every single person I met. Finally, I have grown as a person, because all that I have seen – the bad and the good and all the shades in between – let me catch a glimpse of humanity, in the midst of a situation that I can only define as inhumane.