Blog-post written by Aili Pyhälä and Álvaro Fernandez-Llamazares

Aili & Álvaro on our 1st day in Bhutan

Last month, we were amongst the 300 or so very fortunate participants of the 14th International Congress of Ethnobiology, this time held in the awe-inspiring country of Bhutan. Bhutan… a country that has designated 42% of its surface area as National Parks, many of which are connected by ecological corridors; a country where people are not evicted from Protected Areas; a country where the majority- in their practice of Buddhist philosophy – continue to live in relative harmony with nature, winning over many of the less sustainable and outdated Forest Policy Laws that were adopted in the country in the 1950s (from India, who in turn had inherited such laws from the era of British colonialist-style conservation and forest management). Bhutan, perhaps best known to the world for being the only country that has officially endorsed the Gross National Happiness (GNH) over the Gross National Product (GNP), the latter being the standard global measure of a country’s development. Yes, Bhutan, one of the last places on Earth where the signs of globalization are still largely unnoticeable…

The congress we attended is one organised every two years as part of the main networking of the International Society of Ethnobiology, to bring together researchers, academics, students, policy-makers, lawyers and community leaders from all around the world, including from the hosting country. It was the largest ever international conference organized in Bhutan to date, and her Royal Highness Ashi Chimi, the Princess of Bhutan, was present herself at the opening ceremony, enlightening us with her beauty and her well-spoken words on the importance of traditional knowledge in guiding us into the future. This year, to our pleasant surprise, an exceptionally large number of indigenous peoples and their representatives attended the conference.

Her Royal Highness Ashi Chimi at the opening ceremony

The congress was very well organized and generously hosted by UWICE, the Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environment, a government research and training institute under the Department of Forests and Park Services (Ministry of Agriculture and Forests). The week-long congress (1st-8th of June) took place in the stunning Lamai Gompa Dzong in Bumthang, a valley in central Bhutan, a 12-hour bumpy and dusty yet spectacular bus ride from Paro, where we had all flown into.

The over-arching theme of the conference this time was “Regenerating Biocultural Ecosystem Resilience”, under which sub-themes included topics such as broadening the meaning of conservation, sacred heritage, governance policies, and wellbeing, to name a few. The conference format consisted of a healthy and stimulating mix of conventional academic presentations and more open discussions, talking circles, workshops, cultural presentations, field trips, and even a Biocultural Film Festival! Here we share some of what for us, personally, were the substantial highlights of the conference and what we came away with.

Lamai Gompa, site of the Congress

One of the best sessions that we attended – both in terms of the quality of the presentations, as well as the depth of the discussion that followed – was the session on Indigenous Knowledge and Climate Change, chaired by Rajindra Puri (Univ. of Kent). Puri himself gave a very interesting talk on his recent work reviewing the extent to which the IPCC is taking into account Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Key points that he raised were that:

- The IPCC treats adaptation as if it were something new, something we need to “plan”, as if it were a new “Western” concept, while in actual fact adaptation has always been occurring amongst traditional and indigenous societies;

- The IPCC tends to portray indigenous peoples as helpless victims needing our help to adapt, when perhaps it is the other way around: they are in-depth experts on climate change adaptation who we can learn from;

- The IPCC frames TEK rather simplistically, and continues to call for more evaluations and evidence, as if we still needed to prove that TEK is effective (when local communities know very well what works and what doesn’t, and have surely filtered out the knowledge that does not work over the millennia that knowledge has evolved and been perfected).

Another very good session was that on Traditional Ecological Knowledge, a double session co-chaired by our colleague Matthieu Salpeteur (Univ. Autònoma de Barcelona) and Ashok Jain (SK Jain Inst. of Ethnobiology). One of the best talks in this session was a presentation given by Erik Gómez-Baggethun (co-authored by Victoria Reyes-García, both also colleagues from the Ethnoecology Laboratory). Several fundamental and important points were raised, questions that often get overlooked in conferences which tend to go into great detail on a number of different topics. The talk explored the history and reasons behind the loss of TEK in Europe. The most interesting points raised were that i) non-resilient systems tend to adopt modern knowledge more, whereas resilient systems are more likely to maintain traditional knowledge; and ii) many TEK systems are adapting to change, and we need to recognize this adaptation component. In other words, we tend to hold TEK in a frozen form, lamenting its loss, romanticizing an “idyllic past” (which in fact never existed – not biologically nor socially!) whereas TEK is constantly changing and evolving, like all else. Similarly, there is a systematic bias in the TEK literature towards looking at the past, rather than looking at the present or the future. If knowledge systems are to be the institution and substrate for resilience, we need to start shifting the focus of TEK towards adaptive co-management, and here sovereignty is a key factor.

There was some interesting discussion about terminology, i.e. whether we should use Local Environmental Knowledge (“LEK”) or Traditional Environmental/Ecological Knowledge (“TEK”). While some prefer to use TEK in some contexts because of the cultural continuity component that it implies, prefer to use LEK because they believe relevant knowledge does not necessarily have to be traditional; it can also be adaptive. Philippe Barret (Geyser) in his talk questioned whether the focus in the transmission of LEK is to reproduce or to inspire? Another very interesting and relevant point he made is that they, Geyser, publish on experiences, not practices, because the transmission of TEK must be holistic, not analytic. A similar point was raised by Evelyn Roe, who gave an excellent talk on phenomenological botany and holistic science, illustrating the lessons that she had gained from observing waterlilies in Zambia and how a holistic paradigm of science starting at the observational level could help to build more meaningful and better grounded research studies.

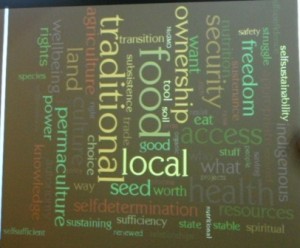

Another excellent session was that on “Visioning Food, Health and Energy Sovereignty: Ways Forward for Research and Practice” organized and chaired by Karim-Aly Kassam and his Research Group from Cornell University. The session was great in that it was more of an interactive workshop than a one-way presentation. We were all asked to contribute our ideas and views on the topic, both individually as well as in small groups, the end result of which included a visually impactful “word cloud” with the results of what participants felt were the keywords related to food sovereignty. Kassam and his group outlined four key elements to sovereignty: ecological possibility; cultural relevance; knowledge capacity, and; institutional infrastructure.

Word cloud of “food sovereignty”

Another very informative and thought-provoking session was that on “Medicinal plant itineraries: new analytical approaches on the production, trade and use of herbal remedies” chaired by Gary Martin from the Global Diversity Foundation. Jan Martinez Agnes van der Valk (Univ. of Kent) gave a very good talk on plants and governance with regard to Traditional Herbal Medicine in Tibet. He pointed out that traditionally in Tibet, herbal medicines did not have any brand names, and all this talk about “quality” “safety” and “efficacy” has been imposed by modern Western firms. We also learned about the new (April 2011) European Union THMP Directive, ordering over-the-counter sale of traditional herbal medicine as illegal, unless it’s already been in use in the EU for a long time (e.g. 30 years).

Sue Evans (Southern Cross University, Australia) also gave a fascinating talk about responsible medicinal plant consumption in Australia, with a historical overview of how certain European medicinal plants came to be used in Australia. An important point she raised is that while traditional methods in preparing plants for use generally involved a very sophisticated method of extraction that resulted in highly concentrated and appropriate doses and minimal plant mass, pharmaceutical companies today use methods that require a much larger volume of the plant, hence placing significantly more pressure on the viability of these plant populations (and sustainable extraction levels), especially when it concerns wild plant harvesting. Similarly, she raised the question of why, in our Western culture, consumers are so interested in where their coffee and chocolate comes from (as apparent in the increasing array of “eco” and “fair trade” labels and certificates), but much less, if any, importance is given to where our plants and medicines come from.

Aili & Álvaro giving our respective talks in the Congress

Finally, being in the country of Gross National Happiness, we were hardly surprised to find in the programme an entire double session on community wellbeing. Aili has written a separate blog on this and GNH, which you can find on the website of Radical Ecological Democracy.

As for the Biocultural Film Festival, it was an extraordinary opportunity to experience through, and learn from, compelling visual narratives about the broad spectrum of innovative approaches in biocultural conservation. Amongst the numerous short films presented, we particularly enjoyed Seeds of Sovereignty, a recent and deeply touching film from the Gaia Foundation and the African Biodiversity Network sharing the stories of a number of communities across Africa embarking on a journey to revive their traditional seed diversity and regain control over their food systems. A free version of the film can be watched online at the website of the Seeds of Freedom Project.

The ISE 2014 Congress was a very diverse and stimulating event that seems to have inspired all of its participants to a degree rarely reached by large conferences. We believe the keys to its success were: a) the excellent organization; b) the very warm and friendly hosting; c) the peaceful setting and milieu, enclosed enough to encourage quality networking and exchange, but open enough to not be too claustrophobic; and d) the incredibly beautiful natural and cultural settings, including the gorgeous traditional attire and humble serenity of the Bhutanese, days starting with morning meditations in the nearby monastery and ending with lively dances around the fire, and the energy and inspiration that all this invoked in us.

Post-Congress trekking in Bhutan’s wilderness