by Minna Vasarainen

During November and December, I have taken part to an entirely new form of company collaboration. KONE corporation and University of Helsinki (UH) organized a research sprint between PhD researchers of UH and members of KONE. The shared journey included three workshops facilitated by Think Company and two weeks of intense working with KONE.

Each of the PhD students were assigned to four different themes with KONE mentors. Based on VETURI programme, KONE had some preliminary topics shared at the application phase of the research sprint, and each of the theme-based teams were given freedom to conduct the research in the basis of participants’ skill sets.

The focus was on solving different kind of societal issues regarding already existing project Veturi of KONE, but regarding means and professional expertise, full freedom was given to participants. This was an important factor already at the application phase since it opened space for everyone to participate. I asked myself, what could an educational scholar like myself give to support solving issues like social sustainability and decided to give it a go.

First week at KONE, our team members, Sanni and Merja from KONE, and me from the university, quickly realized we had common interests beyond the two weeks research sprint. In fact, I had written already in my application a shy wish for shared publication, although the realization of shared publication in an entirely new context and stakeholders is far from self-evident. Nevertheless, the mutual interests guided the collaboration to this direction.

During the second week, our team conducted an extended reality (XR) experiment in terms of agile research. You may read more about the experiment here (link will be available later). The orchestration of this sort of experiment would not have been possible without the strong expertise and technological competence already existing at KONE – the two weeks could have easily passed just by getting to know each other.

Moreover, KONE visit included a wonderful experience for me to get to know Teollisuusoppilaitos (Industrial Institute) and some of the KONE premises at Hyvinkää, Finland. I had the chance to try different sort of VR training modules of KONE – altogether there are already near thirty different ones of them, available globally at different training locations.

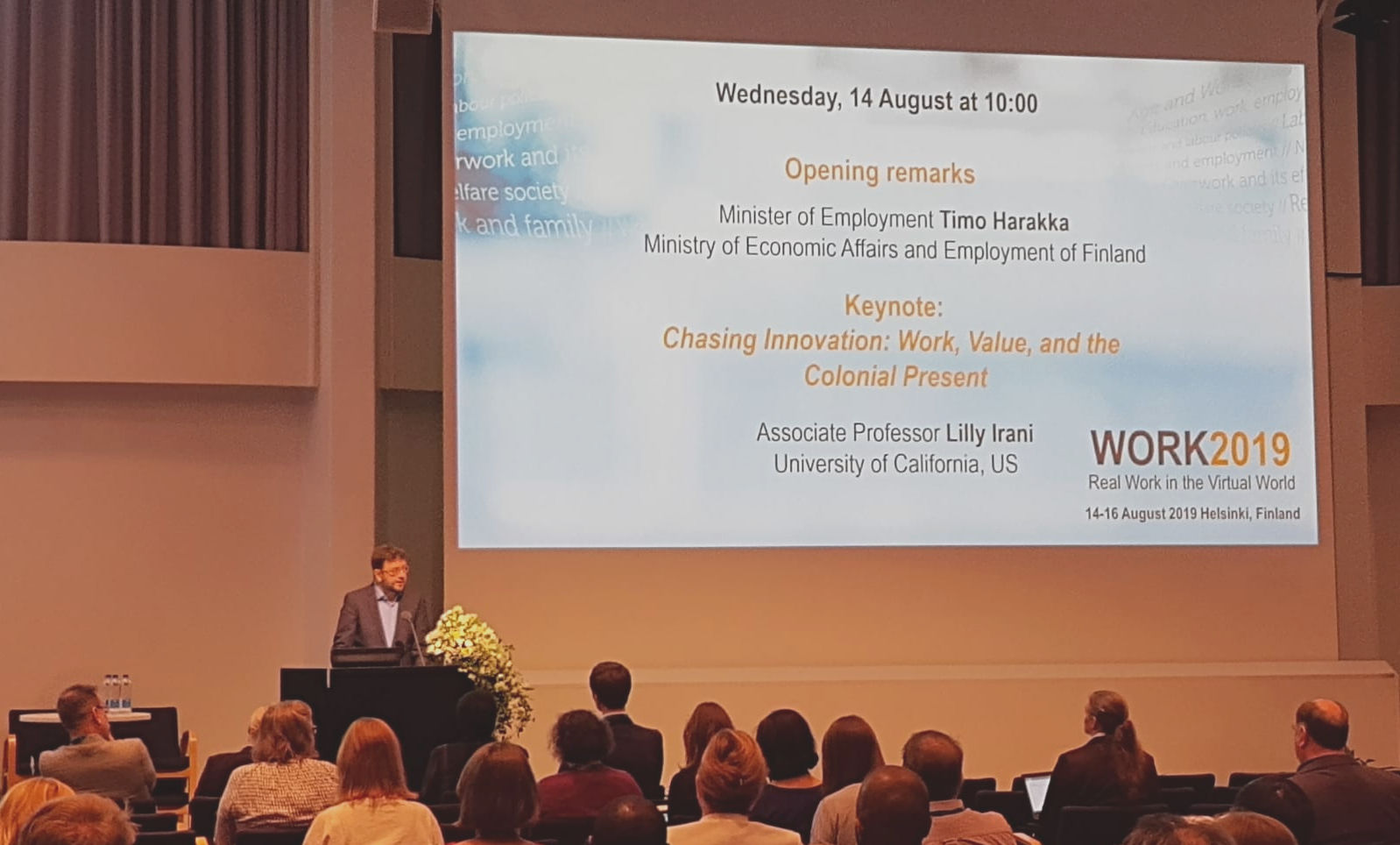

The research sprint culminated at 8th of December to Technology & Innovation talk at KONE. We had ten minutes to present our research sprint experience and its outcomes, and preparing for the presentation, as well as for the previous ones, has given me valuable learning experience on presenting my research topic concisely and clearly. Helsinki Think Company’s workshops also gave wonderful insights for preparing for the presentations!

I can warmly recommend this sort of business visit for any PhD researcher, regardless of the timing of your PhD is. The outcomes from this visit were different to each participant, including KONE employees, and the experience was truly collaborative, as we did and build it together. This also ensured, that the outcomes were beneficial for all. Next, I am up to writing a conference paper in collaboration with KONE’s Sanni, Merja, Hanna, and Viveka, so this was a mere start!