By Maijastina Kahlos, Emilia Mataix Ferrándiz, Anna Usacheva and Elisa Uusimäki

The HCAS Symposium “Mediterranean Flows” was held on Zoom on December 10-11, 2020. As we stated in the rationale for this symposium, our aim was to create a space for interdisciplinary inquiry into the movement of individuals, objects, and ideas, focusing on the Mediterranean region. All of us organizers work on the ancient world, with texts and/or material culture, but thanks to our diverse group of colleagues at HCAS, it soon became clear that contemporary cases of Mediterranean-related movement would provide excellent conversation partners to ancient modes and moments of travel and mobility. This is how “Mediterranean Flows” came to be.

We are happy that we followed the Collegium’s cross-disciplinary vision, as the symposium turned out to be a delight. So many scholars, so many perspectives—so much to think about! We heard excellent contributions by researchers trained in history, archaeology, sociology, anthropology, classics, theology, study of religion, philosophy, and geography.

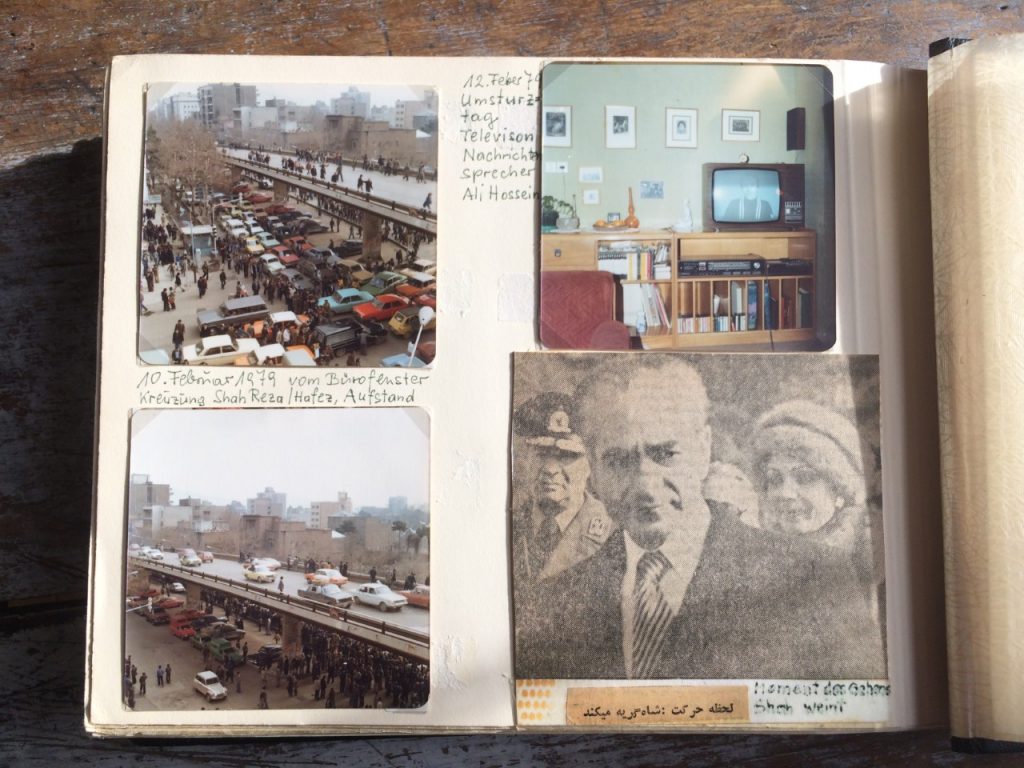

Poster for “Mediterranean Flows: People, Ideas and Objects in Motion”. Photo by Maijastina Kahlos.

MULTIPERSPECTIVES ON MOVEMENT

We started the symposium with a session titled “Mobility–Ancient and Modern”. The two papers delivered by Greg Woolf and Lena Näre worked admirably as the opening presentations of the conference because they invited us to think of movement and connectivity across time and place, both as documented in historical sources and as experienced and narrated by people today. These presentations introduced several useful concepts, prompting us to reflect on different aspects and agents of movement, whether movers and stayers, ranges of distance, direction of movement, or selectivity of flows. We were also encouraged to think about the role of imagination and emotions as driving forces of human mobility—and how these are reflected in imaginaries of daily life, as children’s drawings, for example, demonstrate.

In the second session, Sarah Green expanded our notion of movement by reminding us that movement does not concern only people, objects, or ideas. Indeed, other living beings like animals and insects also move or are forced to move with people. Such travel companions can also influence human travel in unexpected ways. Antti Lampinen, in turn, explored mobility-related anxieties in antiquity, urging us to think of otherness and the process of “becoming Greek”. In his talk, Lampinen captured ancient testimonies concerning the intriguing interaction between movement and the process of building self-identity, whether the question is about the travelers or their hosts.

In the third session, which also focused on antiquity, Peter Singer explored Galen’s testimonies to educational travel and demonstrated how laborious the movement of such an ethereal thing as knowledge could be. Miira Tuominen, in contrast, focused on reception as a type of intellectual travel of ideas and on the change that accompanied it. Both of these topics resonate with our own professional lives that typically involve exchanges, library visits, field trips, and conference travels, all driven by the desire to know more, though Corona has now prompted us to create new ways of acquiring knowledge that we can’t obtain at home. The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria may be right in saying that “Many persons … have come to a wiser mind by leaving their country” (Praem. 18-19). Similarly, another ancient Jewish author observes that “a person who has roamed has learned much”. Yet, we are also lucky to live at a time when technology enables us to come together virtually. Thanks to Zoom, we were able to invite the experts abroad into our own homes and offices.

On the second day of the symposium, we had two wonderful sessions, or in fact three, given that we had to combine sessions 5 and 6 because of some last-minute cancellations. In the fourth session, we studied material culture across time. David Inglis talked about global wine dynamics and related waves of globalization, after which Andras Handl analyzed long distance relocations of relics in antiquity. On Friday afternoon, we heard three papers that ended the conference with intellectual fireworks. Bärry Hartog introduced the concept of glocalisation and read the Book of Acts in light of it, while Elisa Pascucci and Daria Krinovos analyzed labor and transnational mobilities. In the final paper, James Gerrard explored fascinating cases of travel and movement in the Roman periphery.

ORGANIZING A CONFERENCE AT THE TIME OF COVID-19

The symposium went through some major changes because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Initially, we had planned a workshop with invited speakers, who would have flown to Helsinki for two days, and a mainly Finnish audience at the university. During the first wave of the pandemic, we postponed the event from September to December, but it soon became clear that we had to change it into an online conference. We wanted to address as wide and international an audience as possible. Therefore, the conference was advertised in the e-mailing lists of classicists, archaeologists and biblical scholars.

We realized that an online conference is an opportunity to reach a wider and more international audience than would have been possible in the case of a traditional conference. Preparations for an online meeting were also different, but we obtained assistance from the HCAS office and interns. Initially, we were concerned that the online conference would be lacking in the informal social gathering typically enjoyed at traditional conferences. However, to our pleasant surprise, the audience, the speakers and the chairs were very active both in the discussions and in the chat—as well as in the final discussion. In the future, when online seminars and conferences will be everyday life, the social aspect should be developed and informal conversations could be encouraged in many ways, for example, by making use of the breakout room function on Zoom.

This word cloud made of all the abstracts of the conference displays the word “people” as the unifying element of the diverse presentations.

There is obviously much to digest after this conference! Overall, we sought to offer a series of perspectives on the Mediterranean and thus create an event that would encourage us to step outside of our disciplinary comfort zones and enable us to learn from scholars in other fields, whether they study the past or present. We feel like we succeeded in achieving this goal.

We wish to express our sincerest thanks to HCAS, our speakers, chairs, and participants! We especially thank all the speakers for taking their time to prepare and deliver their presentations. The year 2020 was troublesome, and we all had so much to take care of, which makes us extra grateful that you made this event happen. Thank you, or kiitos, as we say in Finland!