On November 15, I gave a short talk at the seminar From Correspondence to Corpora at the University of Helsinki. My 10-minute talk was a confessione of sorts about some of the things I’ve learned over the years working on my own corpus project, and in the spirit of candid corpus shop talk I decided to post it here.

Before I do that, a few words about the seminar: the theme was digital processing of historical letter corpora, and invited speakers included Pia Forssell (SLS), Nina Martola (KOTUS), Marijke van der Wal (Leiden University), and Alison Wiggins (University of Glasgow). Mikko Hakala and Minna Palander-Collin gave a short presentation on normalising the spelling variation in the Corpus of Early English Correspondence with VARD2, Tanja Säily talked about POS tagging the CEEC Extension, and Samuli Kaislaniemi talked about the problematic issues of representativeness with regard to actual writing practices of the past (Tudor women, in particular), the records that survive, and the ‘edited truth’. Marijke van der Wal talked about the Letters as Loot corpus, which consists of about a thousand 17th- and 18th-century Dutch letters confiscated by British privateers during the Anglo-Dutch wars (there are tens of thousands of these letters in the National Archives of Kew). In addition to transcripts, the online corpus (click) includes images of the letters and a wealth of metadata. The transcription work was done partly through crowdsourcing. Alison Wiggins talked about the letters of Bess Hardwick and the corpus Bess of Hardwick’s Letters: The Complete Correspondence, c.1550-1608, which consists of transcripts of the letters, images, search and browse facilities and a range of other valuable information, such as Alison Wiggins’s description of the editing process. These are great resources.

But enough of these well-planned and superbly executed projects. I give you

“From manuscripts to corpus coding: a learning curve

[Hello.] I will conclude these letter sessions with an autobiographical and self-critical account of my own corpus project, the Bluestocking Corpus. This is a manuscript-based corpus of 18th-century English letters which I began to compile for my PhD thesis over nine years ago, after having worked with edition-based corpus compilation for some years. This combination of factors wasn’t entirely unproblematic in the beginning, and I want to bring up some practical aspects of corpus work that I’ve experienced.

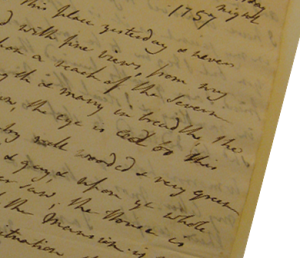

A bit of background: I began the initial work about ten years ago, I defended my PhD thesis in 2009, and I’ve now done about three and a half years of postdoctoral research during which I’ve extended the corpus and still intend to work on it, up to a certain degree. My goal has been to compile a corpus for sociolinguistic analysis of correspondence in an eighteenth-century social network. I began by carrying out a network analysis of the Bluestocking circle, which consisted of scholarly women and men of genteel backgrounds in the latter half of the century in England, and in 2004 I made my first trip to a research library to start the transcription work. I’ve edited most of the letters myself, because so far most editions of Bluestocking letters haven’t been fit for linguistic analysis. This has meant ordering microfilms at first and later on digital images (and now PDFs) from archives, as well as visits to the Huntington Library, British Library, and Houghton Library. There is a wealth of material in these archives, particularly Huntington, which hosts about 7,000 Bluestocking letters: the main challenge is to gain access to it. Compiling a corpus from these starting points is highly work-intensive for one person, and the end result can only be relatively small.

When I began to compile the corpus, I didn’t have much of a size estimate. I was going to do linguistic network analysis, so I wanted letters from members in the Bluestocking circle so that I could compare their language use with the network data I had. This I managed to do quite well. As for the number of words and the number of letters that could be included, it was clear from the start that since I was doing the transcription work alone, I would be able to set a goal only after I’d begun the work and seen how fast I could transcribe. In this case there is no shortage of letters, only limited resources.

Overall, I have transcribed about 220 letters. I’ve also included letters from Elizabeth Eger’s excellent edition Bluestocking Feminism (1999). The word count for the corpus now stands roughly at 250,000, stretched between the late 1730s and the 1790s. These are long letters, many of them from anywhere between four to nine pages. I would like to expand the corpus to 300,000 words or so, based on my (possibly flawed) estimate that some sixty to eighty of these letters would add the extra 50,000 words. In roughly two weeks of full-time work I’ve generally managed to transcribe about 50 or 60,000 words.

But in addition to collecting more material, I also need to revise the oldest sections of the corpus, and here I need to make a few confessions.

Learning often builds upon mistakes, I suppose. I have some experience of that. Before embarking on the Bluestocking venture I had worked as a research assistant in the CEEC project for a few years: as I mentioned, my background was in compiling corpora from letter editions, and I was familiar with the parameters and standards of corpus work in the CEEC project. This had certain consequences to how the Bluestocking Corpus started out.

My intention was to produce a diplomatic edition, i.e. to transcribe the letters to match the originals as closely as possible, but I didn’t have enough experience with manuscripts, and it turned out that I wasn’t quite prepared to achieve this goal. This mostly concerns my first visit to the Huntington Library in 2004, and I want to bring up two things I missed at the time.

The first confession is that I didn’t reproduce line breaks.

It’s not terribly uncommon to leave line breaks out of editions. I haven’t looked at how frequently manuscript-based corpora reproduce line breaks in general; the diplomatic transcripts of the Bess of Hardwick letters certainly do, as do the Letters of Loot transcripts. In my case, leaving out the line breaks wasn’t a conscious decision. Line breaks aren’t included in the CEEC, so I simply did not think to include them.

My other problem turned out to be a spelling practice that marks contraction with a space within the lexeme. In these letters at least, this elision generally appears in past tense verbs and past participles, where the elision of the letter e is indicated by a space: the e is dropped, and a space remains where it would normally be. (Perhaps it has a more sophisticated name. I like to call it the space elision.)

This type of contraction is fairly rare – it is possible that it appears in some of the editions used for CEEC, but I’d never come across it – I wasn’t familiar with this practice at all, so I’m sure you can see where I’m going with this: when I ran into them in the Bluestocking manuscripts, at first I didn’t recognize them (because sometimes the space isn’t very prominent and you can’t always be sure if it’s really there which makes it all the more slippery), and eventually I decided not to include them, because they were entirely unfamiliar to me, and it would have meant going over all the material I’d already transcribed IN THE LAST TWO DAYS. At that point I didn’t know that I would study spelling variation in my PhD thesis and find interesting sociolinguistic variation, and that I would be very interested in the social dimensions of spelling later on.

So: in the beginning I had the mindset and the background of working with editions and very little experience with actual manuscript practices. I had done some work in the British Library, checking old editions against original letters, but my experience and understanding of the field was minimal. I fully intended to reproduce the letters as they were in the original, but including line breaks simply did not occur to me, and those spaces inside words felt somehow alien (space elision!). I eventually realized that I wasn’t actually reproducing the originals the way that I’d meant to, and changed my method. As a result, the overall corpus is currently not consistent in terms of a certain manuscript practice and the layouts, and I want to revise the earliest part of the corpus to change this. This means checking the oldest texts (about 60 letters or so) (edit. that turned out to be an understatement) against the original manuscripts, letter by letter, looking for and pondering over and trying to recognize those spaces. A corpus that has been compiled over a period of time by a single person probably needs to be revised at some point, unless the parameters have been very clear from the start, and this is perhaps not very common if the work has started out as a PhD project.

Skill sets, aims, and resources need to be carefully considered for a solo project. The Bluestocking Corpus consists of simple text files. As a result of the network analysis, I have a lot of metadata about the writers and the recipients. The parameter and text level coding have been done on the basis of conventions in the CEEC, and I’ve added certain codes that reflect the network aspect of the corpus and its manuscript origins. This isn’t XML.

How should I deal with the current range of technical possibilities? Should I POS tag the corpus and consider changing the current coding into something more modern and useful? How should I publish the corpus and include the metadata? The answer to these questions is another question: What can I realistically expect to be able to do, and with what resources?

My answer: I will (edit. should) be able to update the early editorial mishaps, add some new material and make sure the conventions are consistent, and make the corpus publicly available, probably as simple text files, with metadata included in some fairly simple way. This is what I have the resources for.

I don’t believe everyone should learn to code if there are other ways to get things done (I learned this from Heather Froehlich), so tagging and coding would have to be team work, and that would be another project altogether. This hasn’t always been clear to me. We have to think very hard about what exactly we want from our corpora and how much we can reasonably expect to do – I have plans for a new project and a new corpus (so what if I’m a lightweight in all technical matters, pho pho!), so the Bluestocking Corpus has to have an endpoint. We’ll see what the outcome will be like.”

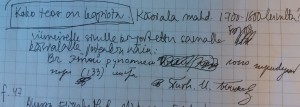

To conclude in an appropriately festive tone, have a picture of my guesstimate of Russian which I don’t know in the least. Notes from the National Library of Russia from many years back. Sadly my transcripts of Russian today would look exactly the same. Let’s embrace our shortcomings.

Well done, me! The note reads: “The whole work is a copy. Handwriting possibly from 18th-19th century? On the last page it’s written with the same hand something like this:” [gibberish]