By Ville Mäkipelto, Timo Tekoniemi, and Miika Tucker

Many texts in the Bible have been preserved in manuscripts that hold different sequences for the same texts. These differences are due to the ancient scribal practice of transposing textual units during the copying of texts. Our collaborative article concludes that these transpositions were often motivated by changes in the ideology and theology of the scribes and their communities.

Our article presents a text-critical study of three documented cases of large-scale transpositions in the textual witnesses to the Hebrew Bible. The method used by scribes to transpose textual units was either by swapping two adjacent units with each other or by relocating a single unit into an entirely different location in the text. Transpositions would often create textual discrepancies at the seams of the intrusion. Sometimes these were left to be, but sometimes they occasioned a series of compensatory revisions to smoothen out the rough edges left in the text. The transpositions vary in their length and nature, but all are in some way related to theological reasons.

Our article presents a text-critical study of three documented cases of large-scale transpositions in the textual witnesses to the Hebrew Bible. The method used by scribes to transpose textual units was either by swapping two adjacent units with each other or by relocating a single unit into an entirely different location in the text. Transpositions would often create textual discrepancies at the seams of the intrusion. Sometimes these were left to be, but sometimes they occasioned a series of compensatory revisions to smoothen out the rough edges left in the text. The transpositions vary in their length and nature, but all are in some way related to theological reasons.

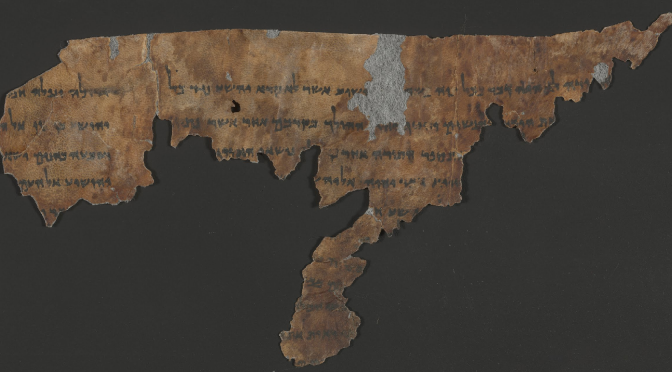

The book of Joshua preserves a tradition which claims that, after the conquest of the city of Ai, Joshua built an altar at Mt. Ebal and undertook a ritual reading of the law with the Israelites (Josh 8:30–35). The position of this tradition after the destruction of Ai is due to secondary swapping of the text with the following verses (Josh 9:1–2). It can be shown from textual details that, in the last centuries BCE, theologically motivated rewriting took place behind the Hebrew textual tradition that is now usually held as the authoritative Hebrew Bible (Masoretic text = MT). The swapping was likely related to this rewriting motivated by the growing importance attributed to Gilgal as the central camp of Joshua and the wish to present the capture of Ai as a more divinely led campaign. The earlier sequence is preserved by the Septuagint (LXX). Moreover, in one Qumran scroll parts of the text are transposed earlier in the narrative of Joshua in order to fulfill commandments found in the book of Deuteronomy.

In 1 Kings, the relocating transposition of the regnal narrative of Judah’s pious king Jehoshaphat (22:41-51 MT/16:28a-h LXX) has incited debate for over a century. While many have noted that the transposition is linked to chronological changes between the two versions, less attention has been given to the theological changes this relocation reflects. In 2 Kgs 3:14 there is a remarkable difference between the LXX and MT editions concerning the name of the Judahite king, whom the prophet Elisha is said to “hold in high regard.” In MT this king of Judah is the unproblematic Jehoshaphat, but in the original LXX this king is the evil Ahazyah, grandson of Ahab (2 Kgs 8:18). It is likely that this theologically awkward LXX reading was noticed by a reviser behind MT, who saw it as inapproppriate for a revered prophet and pupil of Elijah, the greatest prophet of all time, to respect an evil king. However, since in the more original LXX chronology Jehoshaphat dies already before the story told in 2 Kgs 3, the later reviser was forced to also move Jehoshaphat’s reign closer to this story.

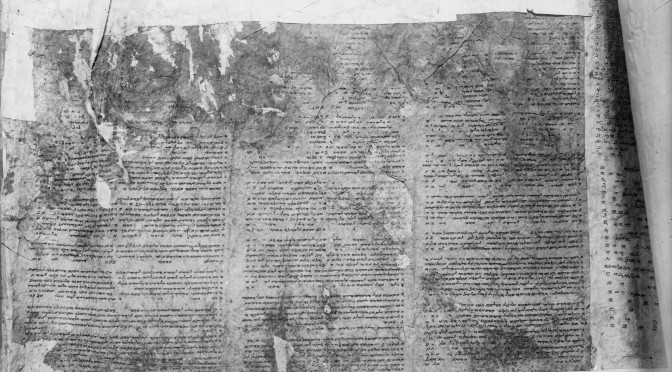

The relocating transposition of the oracles against the nations (OAN) in Jeremiah from the middle of the book (LXX) to the end (MT) reflects a shift in the text towards a more favorable outlook for the exiled community of Judean refugees in Babylon. The sequence of texts in the LXX ends dismally for the Judean refugees: Jerusalem is destroyed and its people exiled; The remaining refugees flee to Egypt against the will of YHWH, who subsequently condemns them; And finally the book ends with another retelling of the destruction of Jerusalem. By transposing the OAN to the end of the book, the MT shifts the focus away from the condemnation of the Judeans towards the condemnation of the other nations. The oracle against Babylon assumes a climactic role in the text that hightens expectations for the salvation of Israel and the demise of its conqueror. The relocation of the oracles from the middle of the book to its end has brought about a series of compensatory revisions. The most obvious of these is Jer 25:14 in the MT, which stands as a “patch” in the place where the OAN used to be located. Other such revisions are found both in Jer 25 and within the OAN themselves.

“Transposition was one of the key editorial techniques in the repertoire of the creative ancient Jewish scribes.”

As shown by the article, scribal interventions have left their traces in the variant manuscript traditions witnessing to the many books of the Hebrew Bible. By studying these traces carefully, we can gain a better understanding of changes that took place in the history of the Bible. Transposition was one of the key editorial techniques in the repertoire of the creative ancient Jewish scribes. When one analyzes the traces of transpositions, together with other scribal changes, it is possible to formulate plausible hypotheses on the early history and changes in Jewish and Christian thought and traditions.

The article “Large-Scale Transposition as an Editorial Technique in the Textual History of the Hebrew Bible” was published in the newest volume of the peer-reviewed journal TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism. The article is open access and can be read here: http://rosetta.reltech.org/TC/v22/TC-2017-M%C3%A4kipelto-Tekoniemi-Tucker.pdf.