Kolmisenkymmentä tutkijaa kokoontuu kolmeksi päiväksi Jerusalemiin keskustelemaan raamatun vaikutuksesta kirjallisuudessa samaan aikaan kun amerikkalaiset armeijan helikopterit halkovat ilmaa yliopistokampuksen yllä ja vain maailmanpoliittisesti merkittävä valtiovierailu löytää tiensä uutiskanavien tiedonvirtaan. Kuitenkin juuri tässä luentosalissa liikutetaan olemassaolon peruskalliota.

Kansainvälisen osallistujajoukon aiheet vaihtelevat heprean- ja kreikankielisten raamatuntekstien tulkintojen historiallis-kulttuurisista haasteista ja William Shakespearen (1564–1616) kuningasnäytelmien raamatullisista viittauksista aina John Miltonin (1608–74) vanhatestamentillisten tulkintojen soveltamiseen nykypäivän maailmanpolitiikkaan. Esitelmissä juutalainen, islamilainen ja kristitty kerrontatraditio kohtaavat ja erkanevat – ja kohtaavat taas.

Jerusalem itse kertaa samaa tarinaa: Katukilvet toistavat hepreaksi, arabiaksi ja englanniksi pyhistä kirjoista tuttuja paikannimiä ja tekevät historiasta ja tarinasta totta. Juutalaisen retkioppaan sanoin: “Kun historia, arkeologia ja traditio kohtaavat – ja jos niiden kertomat tarinat eroavat toisistaan – traditio voittaa, aina.”

Tutkijan tieteellinen esitys ei sisällä tunnustuksellisia elementtejä vaan pyrkii kaikessa objektiivisuuteen, ja esitykset on tässä asiayhteydessä riisuttu kaikista tunnustuksellisista tunnusmerkeistä. (Esimerkiksi ajalliset käsitteet viittaavat “toisen temppelin [historiallisesti todistettuun] aikaan”, ei uskonnollisen profeetan tai jumalan elämään perustuvaan ajanlaskuun – joskin kipa tai kaulariipus antavat viitteitä yksittäisen osallistujan omasta vakaumuksesta.) Tässä ympäristössä kuitenkin myös uskonnollisesta elementistä tulee väistämättä osa poikkitieteellistä jatkumoa ja raja analyysin ja elämyksen välillä hämärtyy. Koska kaupunki on niin avoimen kolmijakoinen, ottaa myös osallistujien oma tieteellinen ajattelu kantaa kolmijakoisuuteen.

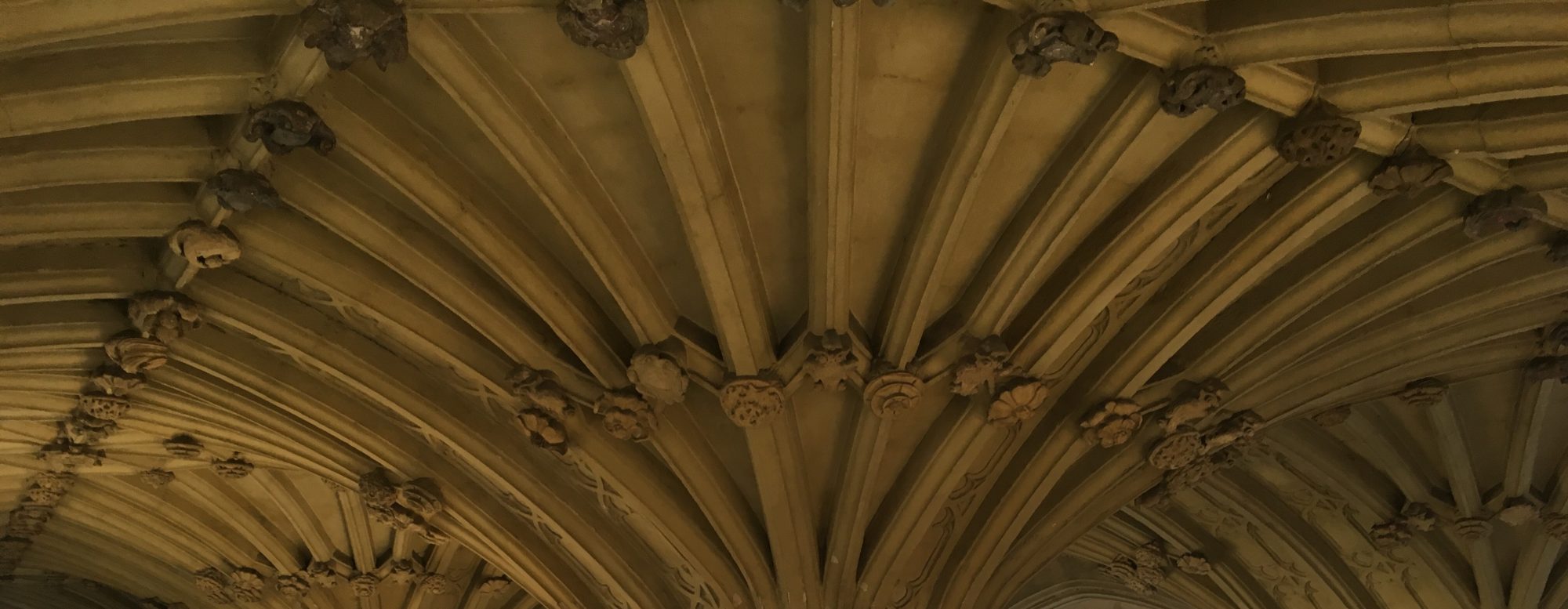

Kirjallisuudentutkimuksen uskonnolliset raja-aidat ylittävä lähestymistapa seuraa osallistujia myös luentosalin ulkopuolelle pyhällä maalla. Tutkijat ovat juutalaisia, muslimeja ja kristittyjä. Joukossa on epäilijöitä ja etsijöitä; joku määrittelee itsensä ateistiksi. Moni on kääntynyt elämässään kerran, toiset vaeltavat vakaumusten varjoisassa välimaastossa. Nyt anglikaani polvistuu rukoukseen tabernaakkelin edessä, uskonnoton kastaa varovasti kätensä pyhään veteen, ja etsijä ostaa päänsä suojaksi lakin, johon on kirjailtu “I <3 Jesus”. Vanhassa kaupungissa minareettien kutsu sekoittuu länsimuurin rukouslauluun ja ristin tien hartaushetkiin. Opilliset yksityiskohdat sulautuvat yhteen, silmät sulkeutuvat, kädet nousevat kohti samaa korkeutta.

Tässä kiteytyy myös kirjallisuudentutkimuksen perimmäinen tehtävä: yhteisymmärryksen luominen ihmisten ja kansojen kesken. Kaupungissa, jossa yksi ja sama tienviitta johtaa eri vakaumusten edustajat kukin kohti omaa päämääräänsä (ja ehkä kohti samaa päämäärää?), tuntuu hetken siltä, että maailmanrauha voisi sittenkin olla mahdollinen.

(The Bible in the Renaissance and its Influences on Early Modern English Literature, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, 22-25 May 2017)