Figure 1. This fresco painting (1590-94) by Agostino Ciampelli depicts a lively and crowded banquet. The painting is situated in Palazzo Tornabuoni, a privately owned Renaissance palace in Florence. (Image by Sailko; public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

My doctoral thesis on early modern Italian food culture looks at affectivity of food and eating. In other words, I am interested in the power that (visual representations of) food and related practices had in inciting both physical and emotional responses. Food, feasting, and cooking appeared increasingly in early modern Italian visual culture, and thus visual sources, paintings in particular, provide rich source material for my study. However, as these images were made for a purpose other than to document the food culture of the era truthfully, they might depict food practices from a rather idealistic or distorted perspective. The elite audiences of the time expected certain elements to be shown and others to be hidden. Therefore, when analyzing the images, we should not only ask what can be seen but also what is missing and why. The concept of apophasis leads us to examine the invisible and unsaid and offers a tool that can be used to study an image as a performance.

The rich and vivid fresco painting by Agostino Ciampelli from 1590-1594 (Figure 1) portrays a banquet of Ahasuerus, the king of Persia. The painting is situated in a private Renaissance palace, Palazzo Tornabuoni, and was commissioned by the then owner of the property, Alessandro de’ Medici. The painting’s banquet is described in the Book of Esther from the Old Testament, but Ciampelli’s interpretation places the event in early modern settings. The feast is set in a loggia, an outdoor yet covered corridor, typical of early modern Italy. The exquisite and softly coloured dresses as well as the vessels emanate early modern fashion and aesthetics. The dining hall is crowded, and the figures are engaged in conversations. The numerous servants are busy performing their duties vigilantly in cramped conditions. As the painting offers so many interesting details and visual stimuli, it almost escapes from the viewer’s attention that, although we are dealing with a banquet, there is very little food on display. Apart from the fruits placed on a table in the right-hand corner, the food is scarce and hardly recognisable. In addition, the act of eating is not depicted, and only the dog actually drinks. Two men in the foreground are holding something that might be a piece of bread or some fruit as if they were about to eat, but their intriguing conversation has overtaken their appetite, at least for now.

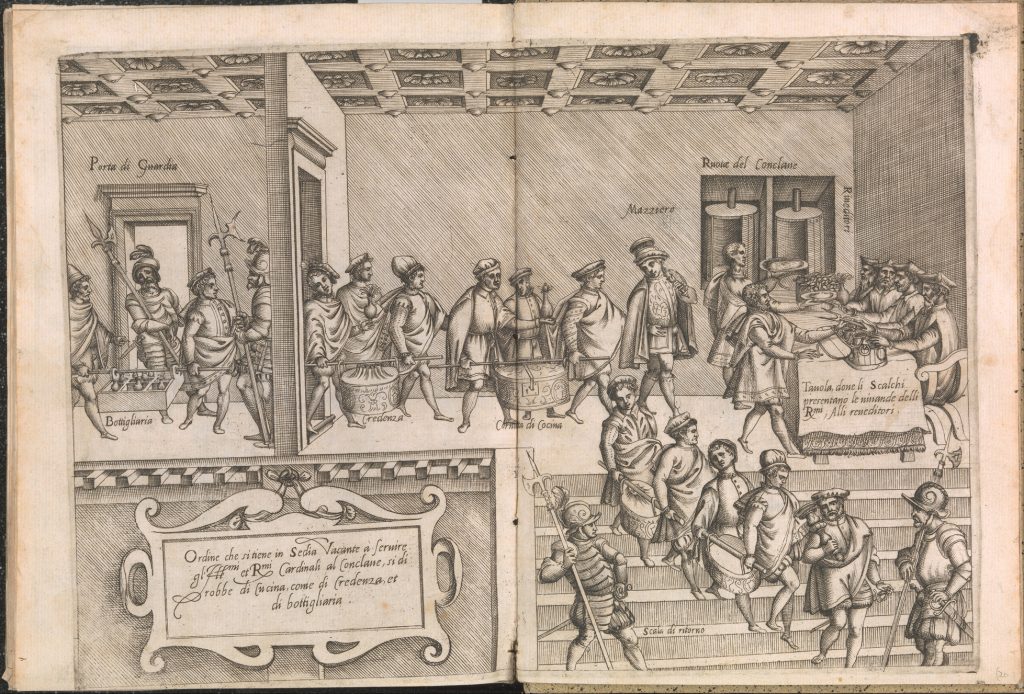

In early modern Italy, the upper-class banquets became increasingly abundant and lavish. The cookbooks of the era often included descriptions of banquet menus from elite feasts, recording several courses with endless dishes served for the guests at spectacular celebrations. In Banchetti, composizioni di vivande e apparecchio generale, the writer Cristoforo Messisbugo, who had worked as a steward in Este court, describes a banquet organised by Ercole d’Este in January 1529. The service consisted of eleven courses and 102 dishes. Bartolomeo Scappi – the private chef of pope Pius V – on the other hand lists in his famous Opera dell’arte del cucinare (Figure 2) altogether six courses and 118 dishes served at a lunch organised for the second coronation of the pope on January 17th, 1566.

The cookbooks together with other records suggest that food was taken seriously, and gastronomy gained increasing significance in early modern Italy. However, the abundant and refined dishes rarely play a central role in the visual culture’s banquet scenes, and the act of eating is hardly ever shown, as Ciampelli’s fresco suggests. Instead, the banquet scenes highlight the beautiful tableware, exquisite dresses, entertainment, and social relations. The dishes seem like a triviality and are often unrecognisable if they are shown in depictions in the first place. Sometimes, the banquet scenes portray waiters serving the dishes to the diners, but even then, the food is often hidden in vessels under the lids.

The notion of apophasis is useful in examining issues that are unspoken or invisible, but whose existence and significance are silently acknowledged. Citing Roumen Dimitrov: “in apophasis silence communicates” and “the unsaid is doing the speaking”. What then, does the “silence” or the “unsaid” – the missing dishes and non-eating mouths – in early modern banquet scenes tell us about?

The absence or scarcity of the dishes in the banquet scenes guides the viewer to overlook the fact that the feasts are fundamentally about an affective and bodily activity – eating. Obviously, eating is an essential for human life, but in early modern Italy, it still seemed too vulgar or intimate to show in a painting. Eating engages the sense of taste, smell, and touch – senses that at the time were considered “lower” and associated with animals, non-European races, and the female sex. Further, a strong appetite for food was thought to be linked to excessive sexuality and loose morals, and thus portraying eating figures could have been interpreted as a reference to other carnal desires too. Therefore, even if food was present in a painting, the figures would not have been shown actually eating it.

Art historian Kenneth Bendiner compares the situation to alcohol advertisements in U.S. in which glasses of wine, beer, and whiskey are poured and lifted but the actual consumption of the beverages is never shown. Although Bendiner does not mention the concept of apophasis, he is certainly describing some sort of elephant in the room: “There is a kind of conspiracy to hide the awful truth that alcohol is for drinking purposes, a kind of lie that everyone knows about, but accepts or hardly notices, because it is not so very important.” Similarly, by not showing the act of eating, the early modern banquet scenes try to avoid portraying the members of the elite as bodily and sensory creatures who enjoy the pleasures of food and drink and have desires and cravings that even might sometimes lead them to gluttony and excess. By framing the banquets primarily as celebrations, social gatherings, or rituals and portraying the figures immersed in conversation rather than eating, the paintings emphasised the figures’ restraint and intellectual values.

Although the “sublime” visual culture illustrating biblical themes, myths, or elite’s dining did not depict eating, let alone gluttony, towards the end of the sixteenth century so-called genre paintings started to emerge, which pictured the life of the common people – peasants, butchers, food preparers and sellers – and introduced a novel way to illustrate food and eating. Artists Annibale Carracci, Bartolomeo Passerotti, and Vincenzo Campi produced works such as The Bean Eater, Ricotta Eaters, and Merry Company (Figure 3) that portrayed lower classes around food and drink, sometimes even eating, and emphasized the physicality and sensuality of the figures.

In Passerotti’s Merry Company five people and a dog are gathered around a table. It is difficult to find a connection between the figures apart from their non-normative appearance and behaviour that made them others in the eyes of contemporary upper- or middle-class viewers. There is the white couple with rough features, gabby teeth and lined faces, whose open sexuality together with the woman’s bare breast conflict with contemporary moral standards. The racialized couple in the background is likewise presented as excessively sexual and primitive with their sticking tongues and pouting mouths, but their skin colour alone would be enough to make them marginalised. The white man dressed in a toga and a wreath holds a wine jar and resembles Bacchus, the god of wine, and thus refers to reckless drinking and indulgence. The dog, on the other hand, was sometimes used as a symbol of voraciousness and gluttony in early modern culture, but ironically, in Passerotti’s painting, it seems the least bestial and uninhibited of the company and thus underlines the primitiveness of the human figures.

The painting’s foods contain references to low status and sexuality. Sausage and garlic were viewed as foods of the poor and rustic. In addition, garlic was believed to strengthen the libido while the sausage could be interpreted as a reference to male and the fig as female sexual organs. These uncooked articles of food are thus to be read as symbols of the figures’ vulgarity that highlight a connection between eating and sexuality, not as an actual meal.

Paintings like Merry Company likely provoked mixed feelings – disapproval, amusement, and confusion – among early modern viewers as they contravened and challenged the conventional norms of visual arts. They pictured the lower-class figures and their food practices in a way that the elite could not have been presented – as coarse, lustful, and even primitive, as an opposite to the restrained dignity that brimmed from the upper-class figures in the banquet scenes. Thus, the imagery in the genre paintings offered the upper classes a means to shape their identity by separating themselves from “the vulgar behaviour” the paintings presented. From an apophatic point of view, the elite could define themselves through negation – “that is not us” – leaving unsaid what they actually were. Of course, members of the elite were also prone to temptations, even though the social norms restrained them from expressing it openly. Hence, it is possible that these images of “others” offered the upper classes a safe way to encounter or process their hidden emotions or desires, without the risk of being associated with the lascivious figures or behaviour.

Anna Repo (anna.e.repo@helsinki.fi) is a doctoral researcher in European Area and Cultural Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her research project “Food Culture in Early Modern Italy. Affects, Gender, and Materiality” looks at the affectivity of food and eating in early modern Italy and explores the bodily and emotional reactions and experiences connected to food practices.

For further reading

- Bendiner, Kenneth. Food in Painting. From the Renaissance to the present. London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2004.

- Dimitrov, Roumen. “Silence as Negation. The Strategy and Beyond.” Southern Semiotic Review 8:1 (2017) pp. 21-32.

- Messisbugo, Cristoforo. Banchetti, composizioni di vivande e apparecchio generale. Ferrara, 1549.

- Repo, Anna. “Ruoka, luokka ja affektit 1500-luvun lopun italialaisessa visuaalisessa kulttuurissa.” Historiallinen Aikakauskirja 120:3 (2022) pp. 275-288.

- Scappi, Bartolomeo. The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi 1570. L’arte e prudenza d’un maestro cuoco. The Art and Craft of a Master Cook. Translated with commentary by Terence Scully. Toronto, Buffalo & London: University of Toronto Press, 2008 [1570].