Figure 1. Site of the Albuquerque Indian School cemetery in November 2023. Photo taken by the author.

In the city of Albuquerque, New Mexico, there are few visible reminders today that the city was once home to an important government boarding school for Native Americans. Indeed, this chapter in the history of the city now exists somewhere between remembering and forgetting. During a six-month research stay there, conversations I had with locals about my dissertation on boarding schools often ended up at Indian School Road. As one of the major streets, which runs across the city from east to west for almost 23 kilometers, the street signs for Indian School Road evoke a history of government policies of assimilation that once shaped Albuquerque. In practice, it appears more like a dead-end street where the historical memory of the non-Native population of the city begins and ends. Deliberately or not, most people have forgotten the school and the role it once played in the local community even as they recognize its absence. In different ways, this absent presence of the long history of forced cultural assimilation is emblematic of historical memory in the US and an important reality for the academic field of boarding school studies.

Empty streets full of history

Walking through the area around the intersection of 12th Street and Indian School Road where the 18-hectare Albuquerque Indian School campus was located between 1882 and 1981, it becomes clear that the school has disappeared from the public eye in a very literal sense. The one building that remains of the original campus is on a dead-end street next to a highway, surrounded by new construction. The other major reminder of a history that has otherwise mostly disappeared under concrete is a makeshift memorial in a nearby park. Passersby have left teddy bears and other toys under a pine tree adorned with sun-bleached orange ribbons to honor the children who are buried in unmarked graves beneath the grass (cf. Figure 1). This place was once at the edge of the schoolgrounds and served as the school cemetery, a site where school officials buried children who died on the premises, often from diseases like tuberculosis.[1] The school stopped using the cemetery by 1932, and in the following decades, the people of Albuquerque mostly forgot about it as the city built a park and a road over the burial ground. There was some debate after the discovery of human remains during construction work in 1973, but ultimately the park remained as it was aside from the addition of an informational plaque in 1999.[2] The city has since put up a makeshift fence delineating the section of the park where the cemetery used to be and put up informational signs (cf. Figures 2a and 2b). However, consultations with Native American communities in 2021 and 2022 have not led to further action regarding the site, as the city has not been able to come up with a definitive plan and continues to examine the best course of action.[3]

The teddy bears that anonymous passersby have left would for some members of the non-Native population be a sign of apophasis, a reminder of an absence they hardly notice. For those who know the history of this place, however, there is no real apophasis, merely a lack of recognition and awareness. Indeed, for many Native Americans, the history and legacy of government boarding schools like the one in Albuquerque is a presence that is still felt acutely. The long history of forced assimilation through education and other policies affects individuals and communities today in small and large ways.[4] The discrepancy in perceptions of boarding school history is especially significant considering that apophasis about the history of settler-colonial violence in the United States is part of a larger inability and unwillingness to see Indigenous communities and their ongoing struggles for sovereignty. Even in a state like New Mexico, where Native Americans make up about 11 percent of the population, the national myth that Indigenous communities are of this place but not of this time persists.[5] Boarding schools themselves have historically contributed to this narrative, because even though they failed to assimilate Native Americans, they presented displays of assimilation that convinced white audiences that Indigenous peoples and their cultures and languages were indeed disappearing.[6] In a sense, the absence of knowledge about boarding school history in a place like Albuquerque is one missing link in understanding this history of erasure. The creators of the improvised memorial at the school cemetery have made an attempt to break through this state of apophasis, drawing attention to the need for recognition by beginning to fill in some of the empty signifiers that point to a half-remembered past.

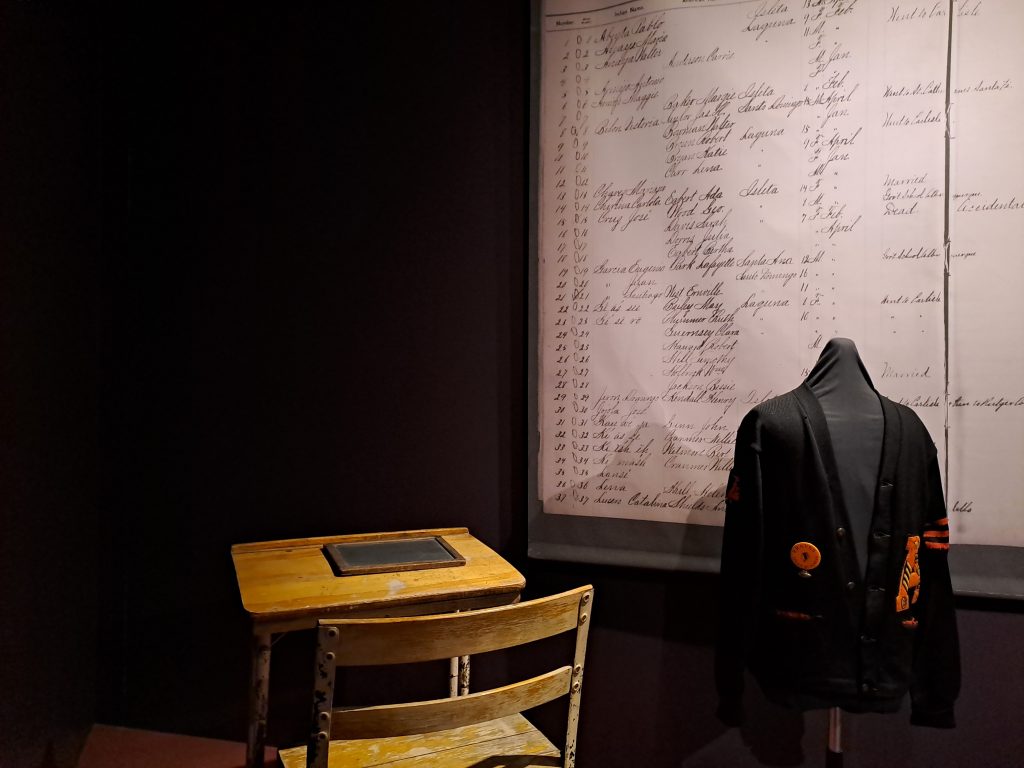

Ironically, the very place where Albuquerque Indian School used to be is now home to one of the most powerful reminders in the city that this is Indigenous land, and that the school failed in its central mission. In the middle of the area where the buildings once stood is the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center (IPCC), which opened in 1976 and serves as a museum, archive and event venue where the 19 Pueblo communities of New Mexico showcase their histories and cultures. Significantly, their main exhibit includes a display about Albuquerque Indian School with a school desk, a letterman jacket from the 1950s, and historical photographs (cf. Figure 3). In claiming the school as a part of Pueblo history, the IPCC highlights their long relationship with it and emphasizes that the people of the Pueblos have outlived assimilationist education and found ways to make it theirs.[7] A similar display at the Albuquerque City Museum gives visitors a general understanding of what the school was and narratively incorporates it into the history of the city. Notably, boarding schools in other places have themselves become sites of commemoration and remembrance. For example, the former Stewart Indian School in Nevada and Phoenix Indian School in Arizona live on as museums dedicated specifically to the undoing of apophasis by writing the past into the present through tours and exhibits.[8] By comparison, the attention that Albuquerque Indian School receives is minimal and folded into other spaces.

A school and a city

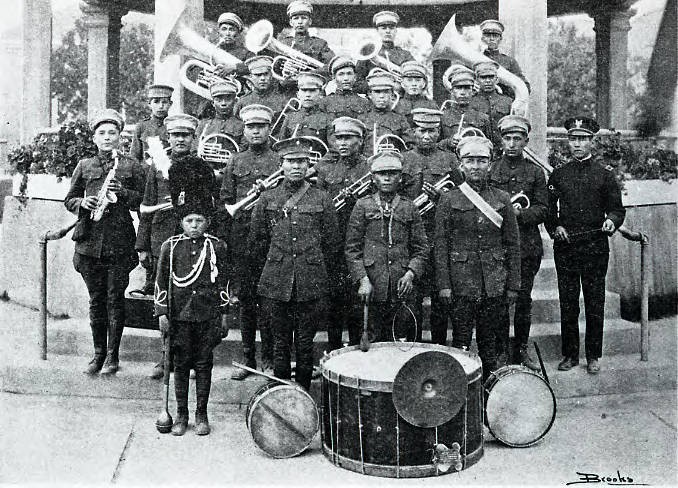

Historical research is invaluable in order to understand the apophasis that characterizes Albuquerque today, because the school was in fact a prominent part of life in the city a century ago. Similar to the hundreds of other government-run and church-run schools that existed, Albuquerque Indian School was a place where white authorities separated Native American children from their families and communities in order to immerse them in a version of American society.[9] Although Albuquerque Indian School was somewhat different due to the influence of nearby Pueblo communities, the school generally followed the same model as the other 25 off-reservation schools.[10] Children took a combination of academic and vocational classes, and their free time included leisure activities that taught the same values and ideologies. Another aspect in which Albuquerque Indian School resembled its counterparts in other places was the existence of a gendered music culture.[11] The marching band in particular (cf. Figure 4) played a central role in life at the schools, providing the music for military rituals and introducing students to a vast repertoire of patriotic and classical music.

The Indian school bands are the focus of my dissertation research and among other things, they offer a glimpse of the relationship that existed between the government schools and local communities. In the case of Albuquerque, historical newspapers in particular offer insight into life in the city at the turn of the twentieth century. Newspapers like the Albuquerque Journal and the Albuquerque Daily Democrat occasionally wrote about life at the school, and they also announced public events. Pupils from the school frequently participated in city parades on major holidays like Memorial Day, and after the school established a band in 1892, it too frequently appeared in public and was a popular attraction. So popular in fact that by the 1910s, the band had certain songs that audiences always expected to hear, such as its signature song, “A Day in the Cotton Field.”[12] From time to time, citizens of Albuquerque would also visit the school, for example to go to concerts or attend graduation ceremonies that were open to the public.[13]

Crucially, as members of the school marching band, the identities of young Native Americans were subject to a type of apophasis as well. On the one hand, the American government sought to erase their Indigenousness and transform boarding school students into model citizens. On the other hand, however, audience perceptions of these bands were often rooted in otherness, as the musical talent of the bands was typically considered all the more remarkable because the musicians were Native American.[15] Even though white audiences were largely ignorant about Indigenous nations and cultures, their insistence on highlighting the fact that these were Native American musicians rather than newly minted Americans illustrates just how uncertain the outcomes of the assimilation project were. Despite their outward appearance, students retained their identities for themselves and in some complex way, they remained Indigenous in the mind of white audiences as well. Wearing a military uniform or playing Beethoven did not mean they stopped being Native Americans, but school officials pretended that was the case, resulting in a state of apophasis that silenced Indigenous perspectives without ever truly making them disappear.

Although the school and its students were an important part of city life for almost half a century, that did not last. As the city changed, marching bands became less popular, and the federal government moved away from strict assimilation in the 1930s, the relationship between the school and the city began to shift and the school lost its former prominence. After the school closed in 1981, public interest quickly turned from the school as a social space to its physical campus.[16] The buildings stood empty for the next decade and quickly deteriorated as homeless people sought shelter there and fires broke out. In response, local newspapers frequently featured complaints about the former school campus. It was called a “blight” in one article, and another writer even compared the ruins of the school to the war-torn landscapes of Bosnia.[17] Rather than an interest in the past or the potential development of the site by the Pueblos in the future, Albuquerque increasingly saw the old school as little more than an eyesore. With the demolition of the last remaining buildings in 1993, the debate stopped altogether. Occasional moments of interest and individual memories notwithstanding, Albuquerque Indian School has effectively disappeared from the city.[18] More recently, Albuquerque’s boarding school past entered the public consciousness again following the announcement that investigators had discovered unmarked graves at a former residential school in Canada in the summer of 2021. Even as this was a crucial moment at the time, it does not seem to have had a lasting effect on public opinion.[19]

Crucially, Albuquerque is not unlike other communities where there used to be a boarding school. In fact, apophasis occurs even in places where these same schools continue to operate. When most of the off-reservation schools closed in the 1970s and 1980s, Indigenous groups took control, as happened with the boarding schools in Albuquerque and nearby Santa Fe. Today, Santa Fe Indian School is a place where Native American children come to learn about their own cultures and the cultures of other Indigenous groups.[20] Whereas its students once appeared in parades on Santa Fe’s historic plaza in the center of the city to show their supposed assimilation, Santa Fe Indian School now teaches young Native Americans to be proud of their heritage. In this way, it raises the next generation in a manner that is in direct contrast to the old boarding school approach. However, despite its important work, Santa Fe Indian School is largely invisible to the general public. Whereas hundreds of thousands of tourists pass through Santa Fe every year to buy Native American art and visit nearby Pueblos, many of them will never hear about Santa Fe Indian School, or gain a deeper understanding of Indigenous experiences in the past and the present.

All in all, apophasis is a useful analytical tool that brings to the fore the complexities of settler-colonial erasure of Indigenous communities and cultures. Indeed, apophasis can highlight the erasure of past attempts to destroy Indigenous cultures, as has happened with many boarding schools. In this case, apophasis draws attention to issues that non-Native inhabitants of a place like Albuquerque have been able to ignore because the city’s boarding school past appears to be present only in its absence. By centering those for whom this history has never really disappeared, apophasis highlights the limits of current conversations about the legacy of places like Albuquerque Indian School, and offers new paths forward. Stories of Native American musicians at the turn of the twentieth century and stuffed toys left in commemoration should invite reflection and give center stage to Indigenous voices past and present.

Vincent Veerbeek (vincent.veerbeek@helsinki.fi) is a doctoral researcher in the Program for History and Cultural Heritage at the University of Helsinki, specializing in North American and Indigenous Studies. The working title of his PhD project is “In Tune with the Nation? Marching Bands and Native American Influences on Music Education at United States Off-reservation Boarding Schools, 1879-1940.” This dissertation examines the history of boarding school marching bands and the experiences of Native American musicians with US assimilation policy. During the 2023-2024 academic year, Vincent was a visiting scholar at the University of New Mexico through the Fulbright program. He recently wrote a blogpost about his experiences in Albuquerque for the Fulbright Commission of the Netherlands.

Notes

[1] For more information, see Joe Sabatini, “A History of the Cemetery at the Albuquerque Indian School,” 2017, https://www.cabq.gov/parksandrecreation/documents/history-of-ais-cemetary_sabatini_joe.pdf.

[2] “Bones Found at Park Site,” Albuquerque Journal, October 6, 1973.

[3] “The Albuquerque Indian School Cemetery at 4H Park.” City of Albuquerque Office of Native American Affairs, web page. https://www.cabq.gov/office-of-equity-inclusion/about-office-of-equity-inclusion/native-american-affairs/4h-park-the-albuquerque-indian-school-cemetery

[4] On the legacy of boarding schools, see Brenda Child, “The Boarding School as Metaphor,” in Indian Subjects: Hemispheric Perspectives on the History of Indigenous Education, eds. Child et al, Santa Fe: SAR Press, 2014.

[5] For examples of recent attempts by activists to reshape narratives about the history of New Mexico, see Simon Romero, “Why New Mexico’s 1680 Pueblo Revolt Is Echoing in 2020 Protests,” New York Times, Sept. 27, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/27/us/pueblo-revolt-native-american-protests.html.

[6] See, e.g., Andrew Woolford, This Benevolent Experiment: Indigenous Boarding Schools, Genocide, and Redress in Canada and the United States, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

[7] On the complex historical relationship between the Pueblo communities and federal boarding schools in New Mexico, see John R. Gram, Education at the Edge of Empire: Negotiating Pueblo Identity in New Mexico’s Indian Boarding Schools, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015.

[8] See https://stewartindianschool.com/ and https://www.nativeconnections.org/community-development/phoenix-indian-school-visitor-center.

[9] On the history of the federal education system see, e.g., Adams, Education for Extinction, Lawrence: University Press of Kanas, Second Edition, 2020. See also Bryan Newland, “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report,” US Department of the Interior, 2022. Another helpful resource is an interactive map of the different types of schools created by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

[10] Gram (2015). On the history of Albuquerque Indian School, see also, e.g., Ted Jojola, “Come the Red Men, Hear Them Marching,” lecture, February 21, 2002, Center for Southwest Research, and Woolford (2015).

[11] At many schools, the boys’ marching band existed alongside a mandolin club for girls. This division reflected notions of gender that shaped much of the boarding school program. On the topic of gender, see, e.g., Katrina A. Paxton, “Learning Gender: Female Students at the Sherman Institute, 1907–1925,” in Boarding School Blues, eds. Clifford E. Trafzer, Jean A. Keller, and Lorene Sisquoc, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

[12] Francis Stanley, The Duke City: The Story of Albuquerque, 1706-1956, Pampa: Pampa Print Shop, 1963, 229.

[13] Theodore Jojola, “Foreword,” in Gram, Education at the Edge of Empire, XIV.

[14] Albuquerque Photograph Collection, CSWR, https://econtent.unm.edu/digital/collection/albuq/id/152.

[15] John Troutman, Indian Blues: American Indians and the Politics of Music, 1879-1934, Norman: OU Press, 2009.

[16] After a period of decline during the 1970s, the Pueblos took over leadership of the school in 1977, which marked the end of the assimilation period, but a lack of resources and dangerous conditions led to the closing of the school. See Jojola (2002).

[17] Albuquerque Journal, January 17, 1992; Albuquerque Journal, June 10, 1992.

[18] In 2005, Professor Theodore Jojola for example created a major exhibit about the history of the school, which was covered quite extensively in city newspapers.

[19] Following the publicity that boarding schools received during the summer of 2021, the US Department of the Interior has launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to investigate and address boarding school history. For the most part, however, there is still a lack of public awareness and attention for this history.

[20] On the history of Santa Fe Indian School, see Gram (2015) and Sally Hyer, “Remembering Santa Fe Indian School, 1890-1990,” PhD dissertation, University of New Mexico, 1994.