If I told you he worked in mathematics, physics, astronomy, and ballistics; if I told you his logarithmic tables were a staple in all fields of science for over a century and that he held the world record for calculating the most digits of pi for over 50 years – would you know who I’m talking about?

Most likely, the answer to that question would be no. The answer would be negative from the majority of Slovenians too, despite him arguably being the greatest Slovenian mathematician. And if I’m honest, even after having competed in a few competitions named after him, I am not entirely sure I could answer with yes myself.

So, who is this mysterious man whose name and achievements seem to be known only by mathematics enthusiasts or those whose knowledge approaches an encyclopedic level?

His name was Jurij Vega (1754-1802), also known as Baron Jurij Bartolomej Vega. A Slovenian mathematician and artillery officer, he graduated as the top student in his class from the grammar school in Ljubljana. After working as an engineer, he joined the army and quickly rose to the rank of “Unterleutnant” in Vienna’s Artillery due to his talent. Due to his dissatisfaction with the available textbooks and equipment, he started writing his own mathematical literature. In 1782, he published his first book, followed by his first set of logarithm tables a year later.

Vega later published more books, including the notable “Thesaurus logarithmorum completus ex arithmetica logarithmica et ex trigonometria,” which is also the topic of this blog, released in Leipzig. Even during the wartimes, he continued his mathematical works. A testimony of a witness even states that Vega was calculating logarithms while cannonballs were flying above his head. Further, he authored at least six scientific papers and achieved a world record on August 20, 1789, by calculating pi to 140 decimal places, with the first 126 and later 136 being correct. Maria Theresa honored him with the title “Knight of the Iron Cross” for his contributions to weapon improvement with his calculations.

Unfortunately, Vega went missing in the middle of September 1802. His dead body was found in the same month on the 26th in the Danube River. The circumstances of his death remain unclear, with some speculating suicide or murder. However, his death was pronounced an accidental drowning.

Vega’s logarithmic tables

The first book of logarithmic tables was published in 1783, with tables with 7-digit base-10 logarithms, which surpassed all other tables available until then in terms of correctness. Many more editions followed due to great success.

Logarithmic-trigonometric Handbook published in 1793 covered the logarithms of the natural numbers from 1 to 101000 as well as the logarithms of the trigonometric functions for angles between 0° and 45° with a step size of 10 arc seconds (equivalent to 1/129600 of a degree).

In later editions, there were also lists of prime numbers and much more. The third edition, the Thesaurus logarithmorum completus contained 10-digit logarithms that were intended especially for calculations in astronomy.

It is said that Gauss criticized the incorrectness of several values in the 10th decimal place, which would be justified since many mistakes were later discovered and corrected in subsequent editions.

However, the tremendous progress in engineering and astronomy would have been impossible without Vega’s tables. Let’s see how they were calculated.

Calculating logarithms was revolutionized when James Gregory (1638-1675) and Brook Taylor (1685-1731) discovered the possibility of representing functions with their derivatives (Taylor’s theorem).

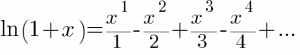

For natural logarithms (with base e), the following series expansion applies:

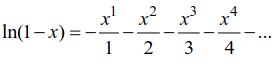

From the formula:

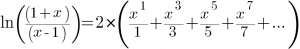

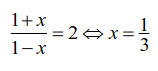

We get a converging series:

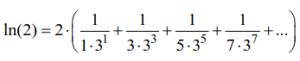

For example, to calculate ln(2), we first determine the value of x. Adding up the first ten summands yields a 10-digit value:

and then we calculate

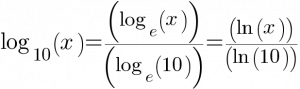

The base 10 and the natural logarithms follow this formula:

To calculate this base 10 logarithm of x, we first determine ln(x) and multiply it by the reciprocal of the ln(10):

![]()

Vega calculated this for all prime numbers up to 100,000 and deduced the logarithms of the others with the formula log(ab)= log(a) + log(b). This was a big undertaking at the time, especially considering all the calculations were made by hand.

Vega and pi

On August 20, 1789, Vega achieved a world record by calculating pi to 140 places, of which the first 126 were correct in the first estimation. The second estimation achieved 136 correct places and is presented below. With his method of calculation, he had found an error in the 113th place in Thomas Fantet de Lagny’s estimation of 127 places from 1719. Vega retained his record for 52 years until 1841 and his method is mentioned still today. He managed to do so by improving John Machin’s formula from 1706:

![]()

with his equivalent of Euler’s formula from 1755:

![]()

which converges faster than Machin’s formula. He had checked his result with the similar Hutton’s formula:

![]()

In conclusion, these calculations allowed for the development of all scientific areas of the time that benefited from precise calculations. Vega’s work was still praised later on, even after his death, for its precision and convenience (with a few exceptions like Gauss). He was able to achieve this by diligent checking and with the tremendous help of his pupils and soldiers under his command. Although he may not be as recognizable now as he deserves, he was, and still is, well-respected in the scientific community. So much so that a crater on the moon was named after him, called the Vega. I realise that his name on the crater is what might have brought you here, but I sincerely hope you stayed for his work and outstanding achievements (partially also because there isn’t much more to the lunar story than that). However, this exhibits that perhaps we should all look up more lunar craters to discover more famous scientists that history doesn’t put the spotlight on, wouldn’t you agree?

Rebeka

Sources:

Faustmann, Gerlinde, “Jurij Vega – the Most Internationally Distributed Logarithm Tables.” Accessed November 27, 2023. https://www.rechenschieber.org/vega.pdf.

Vega, “Détermination de la circonférence d’un cercle,” Nova Acta Academiae Petropolitanae, IX, 1795, p. 41.

Vega, “Détermination de la démi-circonférence d’un cercle, dont le diamétre est=1,” Nova Acta Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petrapolitanea for 1790, Vol. 9, 1795 pp. 41-44.

Vega, Thesaurus Logarithmorum Completus (logaritmisch-trigonometrischer Tafeln), Leipzig, 1794, p. 633.