Contents:

- Introduction

- Distant reading Shakespeare: Our First Case, the First Folio

- Our First Case, the First Folio (page 2)

- Our First Case, the First Folio (page 3)

- Grammatical context

- Case study: Rape of Lucrece

- Observations on the Shakespearean actor network

- Conclusion & References

Our First Case, the First Folio (page 3)

Popularity in numbers

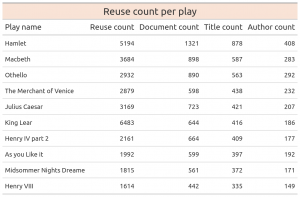

Beyond the visual exploration, numbers can help us to tell which plays are the most popular. Table 1 shows the 10 most popular plays in terms of reuse. What is remarkable is that four of the top 5 plays are tragedies. Hamlet is the most popular play by all counting methods except the total reuse count. Here, however, the so-to-say popularity of King Lear stems from the fact that there is an adaptation of the play by Nahum Tate, and this adaptation alone counts for 2698 of the reuse matches. Of course, an adaptation reciting almost a whole play is full of reuse matches! Therefore, it is necessary to look at the title count to see how widely spread over different works the reuse was.

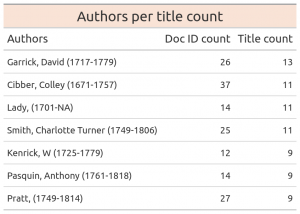

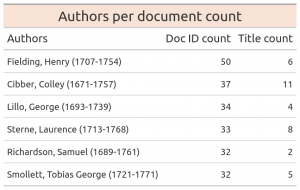

What about the authors then? Can we find any early fans of Shakespeare? It seems that yes, we can. The document count tells the total number of reprints for a title, so for instance Henry Fielding has reused Shakespeare in 6 different works, and these works have altogether been reprinted 50 times. Both numbers influence the conception of Shakespeare. Of course, something that was printed many times sold well and was popular among the audience of that time, whereas the number of different titles might tell how widely the authors themselves were inspired by Shakespeare.

This perspective on our data supports previous research on Shakespeare. David Garrick was an actor and playwright known for playing Shakespeare and restoring his plays. Before him, the plays had been “improved” by many eager editors, and Garrick played an important role in bringing Shakespeare back to the original works that we know today (Stone, 1950). Colley Cibber is known for his adaptations of Shakespeare’s (historical) plays, and George Lillo was a supporter of the Shakespeare Ladies Club, a group of women who strongly contributed to restoring Shakespeare on the stage in the 1730s (Brown, 2017). As to Henry Fielding, he was an English novelist who often alluded to Shakespeare. The exclamation “O, Shakespear, had I thy Pen!” illustrates aptly his admiration of the Bard (Lindboe, 1982).

Since these authors appear on the top of our dataset from this perspective, it indicates that the beginning of the 18th century was an important period for the canonization of the Bard.

What’s in a play?

The above peeks into data have started to unveil the story of Shakespeare canonization. Zooming even more in, we also explored what parts of the plays, in particular, were often reused. This was done based on the cluster ids. The reuse is clustered by the location of the reused text in the original First Folio so that we can count how many times a certain exctract has been used. For this, an individual id (the column “clust” in the data) is given by the algorithm that groups together reuse cases that come from the same part of the original work. For instance, the cluster 215114 matches all reuse from the scene of To be or not to be in Hamlet.

The clusters tell a more detailed story about what was found interesting in the plays. Counting the occurrence of every cluster in our data, similarly to the plays described beyond, we retrieved the most reused clusters:

Perhaps surprisingly, perhaps not, the most popular cluster is from Act 3, scene 1, Hamlet, where Prince Hamlet contemplates on life, To be or not to be? Our quantitative analysis thus implies that this top quote of Shakespeare we know today was already the most known at the investigated period. It appears in various contexts in the dataset.

The second cluster is from Act 3, scene 3, Othello. It also has a philosophical message, comparing honor to material possessions. Looking at the titles, and close-reading some examples, we observed that this text was often reused in works about ‘the art of speaking’ and rhetorics. So, here the appreciation seems to come from Shakespeare’s talent for writing great speeches. Moreover, Henry Fielding reused Othello a lot in his main novel, Tom Jones.

The third cluster is also from Hamlet, from the scene where Hamlet sees the ghost, which is a turning point for the whole play. This cluster appears in writings about Shakespeare, and in ‘the art of speaking’.

The fourth clusters brought us to new perspectives. The farewell speech is a soliloquy given by Wolsey, a cardinal, for his sudden downfall. Here again, Shakespeare mixes aesthetic and ethical questions that become embodied through a complex character. The dramatic last speech has apparently not left the audience cold. However, the reuse contexts are somewhat surprising. The cluster is picked up by Elizabeth Montagu (1785) who praised Shakespeare and defended him against Voltaire’s attacks in France. She uses Wolsey as an example of how force and pathos are expressed in the words of a fallen statesman to emotionally engage the audience. The same cluster is picked up by Noah Webster to illustrate a grammar book meant to American children.

The last cluster of the top five, Mark Antony’s funeral oration for Caesar appears on the list mainly thanks to two authors. Again, Elizabeth Montagu uses the play as an example to praise the skills of Shakespeare: “Is there any oration extant, in which the topics are more skillfully selected for the minds and temper of the persons, to whom it is spoken? Does it not by the most gentle gradations arrive at the point to which it was directed?” The other author increasing the reuse of this cluster is John Sheffield who wrote an adaptation of Julius Caesar. The cluster also appears in a work titled “Rhetoric made familiar and easy”.

Together, the popularity of these clusters indicate that soliloquies were prominent extracts to reuse, and that his rhetorical strategies have influenced and been admired by generations of authors after him.

Reflections

The variety of ways the plays have been used – from admiring his talent to teaching grammar – shows that Shakespeare was a multifaceted author, and that his present conception has been shaped by many factors. While the findings presented here are not surprising, the assumptions and general thoughts about what made Shakespeare popular have not previously been quantified in this way. Now, we can say with more confidence that ‘To be or not to be’ has been one of the most known quotes since centuries. Similarly, it is important to point out that people who are known for restoring the Shakespeare on the stage also appear dominant in our data, indicating that they really had an influence on how the canonization of the Bard unfolded. If we were to use the same methods on another, less researched author, we would be quite confident that the findings from this kind of reuse data are relevant and enlighten us on their reception.