Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Resources

2.2. Methods for Data Visualization

2.3. Methods for Analysing

3. Data Analysis

3.1. Author’s Number and Publication Year

3.2. Location

3.3. Language

3.4. Authors and language

3.4.1. Author William Willymott

4. Qualitative Analysis

4.1. On Inspiration; De Rerum Natura in Milton’s Paradise Lost, and the Lineage of Influence

4.2. The Epicurean Lucretius

5. Challenges and Difficulties

6. Further Research

7. Division of work & reflections on learning

8. Sources

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to study and analyze the use of Latin quotes from the poem De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) in mainly English texts from the 1700s and 1800s. The poem was written by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius sometime in the first century BC, with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy. The poem is divided into six books and it explores topics such as atoms, divinity, universe and space and subjects such as the human mind and soul.

The aim of this short study is to gain an insight on how prominent Lucretius’ work is in over 1500 years after De Rerum Natura was initially written; the use of quotes from De Rerum Natura functions as a metric for his popularity, and the texts the quotes appear in reveal other details, such as in which genre is Lucretius still relevant, what time period, in what language (nation), and so on. Other details of focus are context, in what context is Lucretius mentioned, if at all, and when is the quote used, or whether he is mentioned at all. Other recurring patterns will be noted, such as whether Epicurus is mentioned or if similar topics occur often in relation to the quotes. The use of the quotes will additionally be analysed in some non-English texts, of which there are not many. Our research questions are the following:

- Where in the secondary texts do the quotes occur? (Beginning/Middle/End)

- What are the genres of the secondary texts?

- Which period is the most active or silent period for reusing ?

- Who reuses most from DRN?

- What are the languages of the secondary texts?

- What is the gender of the reuse authors?

- Is Lucretius mentioned or named in the secondary texts?

- Is Epicurus or Epicureanism mentioned in the secondary texts?

2. Methods

In this section, we document and explain the data resources and methods that we used for collecting and analysing the data.

2.1. Data Resources

De Rerum Natura worked as a common denominator for the quotation data and a starting point of our research. Various methods were employed in accessing the relative data. Major resources for example text reuse data and their full texts in txt file, metadata on texts and authors are provided by the course. We first examined a text reuse example spreadsheet with 11212 rows of reuses of De Rerum Natura and were meant to choose five instances of text reuse. These five instances were supposed to be chosen randomly. However, as our plans changed and we decided to go with ten most used quotes, we were offered a spreadsheet of all the editions of which the text reuses were retrieved. This spreadsheet contained metadata such as the topic, language and physical size of the publications and also additional info about the author and place of publication. Each item had a link to the original texts in Octavo reader, so we were able to see the texts in their original form and examine the context.

With the help of the course teachers, we successfully got a spreadsheet of 334 rows containing combined data of the top 10 most used quotes from De Rerum Natura, in which we clustered some overlapping instances together and thus downsized the number to the top 8. After clustering, a new file was created where the overlaps had been removed. This file of top 8 quotes with 269 observations and 25 variables was the data we mostly analyzed and worked with. The information with regard to text primary with their links, text secondary with their links, name of the author, year of publication and the title of works was readily available.

Resources in relation to our research questions concerning the genre and language of the works, the gender of the author, the location where the quotes appear, or in another word, which section did they appear (beginning/middle/end) were mainly gained through manual checking via Octavo. By reading over the original contents of works, data regarding language and the location was confirmed; By clicking the title of the works, it led us to ESTC (English Short Title Catalogue by British Library) where contains more detailed documentation such as subject and genre of the works, however, there were only a handful of works with such information available. About two-thirds of the data regarding the genre were obtained through a variety of online searching, for example, on Wellcome Collection, Google Scholar, and some other collection websites offered by different universities. For those unclassified early and late modern English literature, which accounts for nearly half of the whole data, we classified them ourselves based on our understanding and reference from ARCHER (A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers).

2.2. Methods for Data Visualization

To visualize the data, we first used the online application offered by Stanford University, Palladio, to get an initial idea of the graphs produced by the data and get some guidelines for further analysis. R programming language and Rstudio acted as the most important and major tool for ultimate visualization. ggplot2 and dplyr were the two principal packages that contribute to plotting the graphs.

2.3. Methods for Analysing

Data results and findings were classified into different categories: location, authors and years, language, genre, reuse frequency and analysed through horizontal and vertical comparisons. First, analyses and conclusions were made in different categories respectively. Second, a comparison was made among different categories. Last, the final overall analysis of the work is conducted in a combined method that contains both quantitative and qualitative research.

3. Data Analysis

3.1. Author’s Number and Publication Year

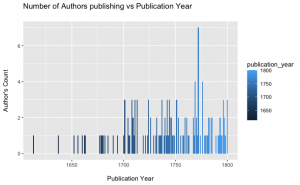

As is shown in the picture above, the publication year on the X-axis represents the timeline of the data starting from the 17th century and ending in the 19th century and the author’s count on the Y-axis represents the total number of authors in that particular year. From the early to late 17th century, large gap spaces dominated this period, or to put it differently, it was a relatively silent period that only a few reuses occurred with the number of the author no more than 1. From the 18th century onwards, reuses started to crowd through the whole hundred years, particularly concentrated around 1775s when the highest number of authors in the very same year reached 4 and had the peak happen twice. The average reuses number of the remaining data was 2 and 1. However, again, the most obvious peak came with the non-available data because of the missing resources of those early collections.

3.2. Location

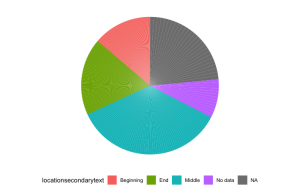

In terms of the distribution of location of reuse quotes, although here we did not provide a definite figure on top of each section in the picture, it is still not difficult to find out that quotes appearing in the middle of the works made up the largest percentage, and this was followed by the end ending location. The proportion of reuse quotes appearing in the preface, introduction, or more generally the beginning section, was relatively small. Due to the lack of access on Octavo to original resources before the 1700s, the N/A and no data accounted for a rather large share of the whole data. To sum up, it can be argued that later authors had a preference to reuse the quotes in the middle of their works and only a few of them have the quotes appear in the introduction part.

3.3. Language

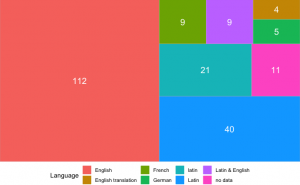

Next, we move to the language. The picture above shows the proportion of the major languages of the reuse texts. Each square with different colours represents different languages and forms of the reuse, for example, Latin & English denotes the text was written mainly by the two languages. The size of the square reveals the proportion in the whole data. Unsurprisingly, the percentage of text in English was far higher than that of any other languages with the number of works written entirely in English alone standing at 112, and this was followed by Latin with the number of works exceeding 61. However, the not unified spelling (initial capitalization) during our data filling resulted in having the same language be divided into different squares which should have been merged. Works with language in French and German accounted for the least proportion excluding those unimportant and similar data. Therefore, We may arrive at the conclusion that English works were more active in using the top eight quotes from DRN.

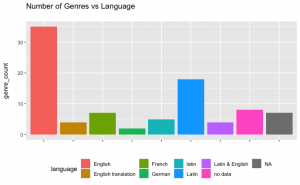

3.4. Genres and Language

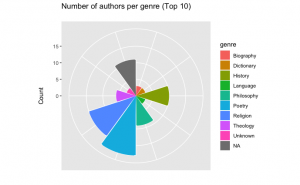

Despite having some issues with labeling the data, we managed to produce clear and coherent graphs. After careful data sanitation, we can see that the most common genres of the reuse works are poetry and religion. When we take a closer look at the works in our dataset, a large number of the works, indeed, seem to be poetry collections and religious texts.

When comparing genres with language, English was clearly the most popular language in all genres, followed by Latin. It is important to notice that some of the English texts are not originally in English, but translations from other languages such as French. The original versions of these translations were not found in our dataset.

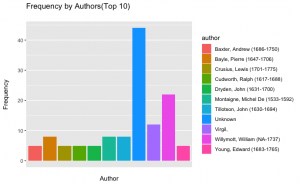

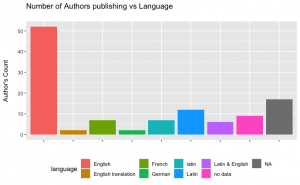

3.5. Authors and language

Thanks to the metadata, we were able to find out which of the authors quoted DRN in their works the most. Unfortunately, information was not available for many of the items, so the largest bar in our graph is unknown.

After defining and labeling the language of each of the reuse items, we were able to combine authors with the language they used. Most of the authors used English in their works, followed by Latin. French and German were also used, by equal proportions.

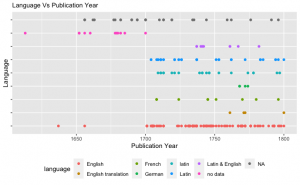

We were also able to track the usage of different languages in the publications throughout the years. We created a line plot with the languages and a timeline of publication years. It was interesting to notice that the popular languages such as English and Latin were used constantly everywhere in the timeline but the languages that were used less were also only used during a certain time period.

Because some information was not available for all the items in our dataset, there is a significant amount of data we could not label. They appear in the graphs as “no data” or “NA”. However, we mostly wanted to find out the largest proportions such as most popular genres in the dataset, and the non-labeled items did not form a large enough percentage to distort those results.

3.6. Author William Willymott

The most prolific author that we can identify is William Willymott, a linguist and author of a Latin textbook that appeared multiple times in the dataset. Willymott’s presence is to be attributed to a that recurring, altered (improved) editions of a certain theological dictionary. The dictionary, by the name of The Peculiar use and signification of certain words in the Latin tongue: or, a collection of observation, wherein the elegant, and commonly unobserved sense of very near Nine Hundred common Latin Words is fully and distinctly explained in proper Englishes, translated from the truest copies of the purest Latin Writers; and intended to be read, or translated back again into the original language (1714), does not appear to have left a strong imprint on the annals of history, and Willymott, a grammarian of the 17th century, himself appears to be a mostly obscure figure, if our searches are to be trusted – few things are to be found beyond footnotes, occupation and date of death.

The several editions themselves were of significant interest; many of them, if not all, have small alterations in the texts, with added information to the definitions, which they themselves could be of interest. Unfortunately, the group did not have the capacity to look through all the works, although we’re confident in the observation that these are, in fact, different works. Lucretius’ text appears in Willymott’s dictionary (presumably) as an example of a Latin text, in which words Willymott is translating appear in proper context; while Lucretius is mentioned as the author, the group believes that it does not appear to be a celebration of the poet; indeed, the text is there in the capacity that any other Latin text could be; just an example to cherry pick words from.

4. Qualitative Analysis

4.1. On Inspiration; De Rerum Natura in Milton’s Paradise Lost, and the Lineage of Influence

Our initial foray into the search of popular texts quoting Lucretius’ Latin Quotes lead us to a number of texts (list provided by Mikko) that we decided to examine; while this initial approach was abandoned in a few weeks, and the list of texts was replaced with another, one of the texts we got a chance to familiarize with suggested an additional layer of analysis; inspiration of De Rerum Natura beyond quoting of the initial text.

The list provided by Mikko offered texts with the most mentions of De Rerum Natura), with the assumption that Latin quotes should follow. The list, mistakenly, suggested that Milton’s Paradise Lost (book ten) quoted Lucretius, but a read through revealed close to no Latin at all – the search program had mistakenly assumed footnotes at the end of the “book” (the “new edition, with notes of various authors”, by Thomas Newton almost has an educational purpose to contextualize the text) of Lucretius’ and Milton’s literary connections. The group decided to look further.

While no quotes that could be attributed to Lucretius could be found in Milton’s masterpiece Paradise Lost, “13 parallels between” (Hardie, 1995: 13) the two works could be founds; these parallels came in the form of passages that could be considered similar in theme and nature – one just wrote in Latin, the other in English, which disqualified these parallels. However, it appears to be clear that Milton “did plough through all four athores de re rustica, Ciceri, the poets Lucretius, Virgil” for his academic work (Poole, 2017: 64), and that Lucretius was not unknown to him. It is clear that academia has traced Lucretius’ work to Paradise Lost – it is of value to keep in mind that an influence can be seen beyond direct borrowing in forms such as homages; these are however often up to interpretation, and unfortunately difficult to measure, unlike direct quotes. Quotes, however, do not necessarily denote anything beyond the superficial; it is the context in which the quotes are used that could show the author’s true intent.

4.2. The Epicurean Lucretius

In researching the context of the quotes, and in particular looking for similarities, the group discovered that the name of Epicurus, the ancient Greek philosopher, would on several occasions appear in the vicinity of a quote by Lucretius; on a deeper look, the two appeared to be intrinsically linked.

Though roughly 200 years separate Epicurus (341-270 BC) and Lucretius (c. 99-c. 55), the latter is still considered, through his only known work De Rerum Natura, as Epicurean; the follower of Epicurus’ ideas of Atomism (early scientific notion of most everything being composed of Atoms), the enjoyment of life as being a centerpiece of the human experience, and the omnipotent presence of God(s) not having too strong a presence in peoples’ lives (Seabrook, 2015). Interestingly enough, Epicurus himself speaks of the power of legacy, having no actual literary work survive into the present day (or likely even past antiquity) – yet he lives through Epicureanism, and authors that followed his suit (Seabrook, 2015).

The group managed to find roughly 18 instances of Epicurus being mentioned in some capacity by different authors, more if new editions (published usually within 15 years of the original edition) would to be counted, which the group decided against; after all, the number of Latin quotes allow us to look at Lucretius’ possible influence on other authors (and ideas) – the same works by the same authors, reprinted with minor differences would surely not count as the spread of influence, unless one tracks the popularity of that specific author.

What the group found to be of special interest, was the discovery that out of these 18 instances of mentions of Epicurus, 14 come in the form of tying the ideas present in Lucretius’ writing back to the ideas of Epicurus; Epicurean (“Epicurean Doctrine”, “Epicurean”) appears 11 times, while Epicurus is brought up as Lucretius’ “Master” (“His Master Epicurus”) thrice. Out of these 18 examples, roughly ten would belong to theological works, with possible philosophical undertones (as it very much used to be the 1700s). Interestingly, these mentions are greatly diminished after 1749, with only three mentions of Epicurus happening after – it however difficult to state anything with confidence about this event, as most of our quotes in general come from before that period.

Our qualitative analysis suggests that Lucretius, when mentioned at all in texts without Epicurus, mostly comes as a name below the quote (as a source of the poem, attributing the latin text to the poet); when talked about in more depth, he is most often referred to as a follower of Epicurus, his work primarily an example of Epicurean thinking. It is also important to note, that Epicurus and the Epicurean lineage was found only in English texts; while our lacking knowledge of Latin and German might contribute to missing out mentions of his name or misunderstanding the context in which the philosophers could appear, we feel confident that mentions of Epicurus might also be tied to the language.

Without Epicurus or ties to Epicurus, Lucretius appears to be mostly known for his poetry, as evidenced by the large collection of poetry collections (surpassing all other genres in number), to the point that sometimes his name is not even mentioned when the poem is presented in a collection.

5. Challenges and Difficulties

The beginning stages of this study brought forth a number of issues which impacted in various ways our progression with the course work and study, most importantly our ability to mount a solid and effective plan in time for the final presentation, and beyond that on the organization of our timetables. These issues should be taken into consideration, as they might have an effect on the final outcome of this study, despite best efforts to try and get around the challenges that the group faced. This section will go through and explain the issues we, as a group, faced and how they may have had an effect on our study.

An early difficulty with the study was the fluidity, and freedom of the topic, as well as the approaches, resulting in the topic of this study changing and altering a number of times; some approaches were deemed too difficult, some we did not understand the limitations of. Whilst this may not necessarily be an issue, we were working with a time constraint, resulting in periods when the group did not know how to proceed with the study, and short, concentrated periods when everyone tried to do their best and move forward, despite not always feeling certain about the direction. Technical issues created another obstacle: several group members were unable to access the Slack channel of the course, where most of the info about the assignment was posted. Thus, the few of the group who managed to access the Slack channel had to keep the rest of the group updated whenever new material was posted into the channel. What was different in this course compared to others was the fact that most of the information and materials were available through Slack and Google Drive instead of Moodle. Looking back, it might have been easier to work with the different datasets and spreadsheets through Moodle. We all would have certainly had access to Moodle, and we wouldn’t have had to scroll the Slack conversation up and down to find the links to the data.

The crucial moments of everything coming together happened just a few weeks before the final presentation, which resulted in a haphazard first draft of the current study; said presentation was built from the ground up in a hasty manner, discarding months of earlier work. Changing and altering the topic came not out of the group’s indecision, often it felt as if the progress was very much out of our hands, depending on what data (and in what form) the group was provided with. It was all rather a case of trial and error, where we came up with and suggested a topic that we would then start working on, only to be told it might not work, or finding out by ourselves that the approach did not end up. While the approaches changed a number of times in a myriad of ways, the topic (search and analysis of Latin quotes) itself has stayed similar in theme, if not in approach and execution.

A difficulty that came with the language, and the subject of the task itself, was to be found in Latin. A minor inconvenience, but nonetheless limiting, Latin being core to the study meant that leaps of fate sometimes needed to be taken in regards to genres, context and manual tasks when searching through the texts. An issue that likely is universal to the course, the lack of understanding Latin, and De Rerum Natura itself, strongly limited our ability to pick up on clues and relevant pieces of information, requiring us to retrace our steps, or move on.

Indeed the manual searching through the texts was largely all that was suggested by the end of the course when it came to working outside of coding. Most, if not all of the group members approached the study with the assumption that a notable section/part of the study would involve some sort of manual, perhaps even “scholarly” approach; finding relevant information through literature, perhaps even working in some capacity with qualitative data. The study and course work however quickly revealed itself to be completely reliant on computer science, in almost all areas of the study; manual work was limited to the wading through of a relatively large number of texts. Par the teacher’s advice, we decided to leave in one of the early attempts (Chapter On Inspiration; De Rerum Natura in Milton’s Paradise Lost, and the Lineage of Influence) for context purposes.

The key issue, however, was, at the end, a simple one; this group is the only one without a member with a background in computer science. We were first told we would get the help of a computer scientist on the course, however, as time went on, we quickly realised that it was something we would have to manage without. It required copious hours of hard work to have one of the members of the group self-teach and learn the use of R in order to produce the graphs that are crucial to this study, a testament to the tenacity of the few students who took up the challenge. With the issues concerning the topic, the data we would have to manually go through and the lack of a computer scientist, the beginning of actual work and analysis was constantly pushed forward leaving us with only a matter of weeks to complete the analysis required for this paper.

Once we were able to proceed with the correct data we realised a large section of the data was unusable. Quotes that are used in the texts that were published any time before the 1700s were not viable. Despite not being able to use multiple texts in our data set, we manually went through approximately 250 texts and noted the topics of interest by hand. This created issues with generating the graphs, as the data entries did not follow a certain pattern. This means everyone in the group noted the topics of interest in a different manner, as we had not agreed on what specific words to use when referring to a certain topic. As the texts published before the 1700s were not viable, there were also sections that had no data entries at all, which presented a further challenge with creating the graphs. Consequently, the sanitation of the data was difficult and time consuming. Would there have been more time and experience with the use of R and similar data sets, these issues might have been avoided.

The constant uncertainty, the lack of knowledge and experience in coding and the time constraint were constant issues throughout the course of this study – this might have impacted some of the hasty decisions, the quality of the coding, and the limited number of approaches; a constant push-and-pull between reinventing the project and staying on schedule and with the originally decided upon theme.

6. Further Research

The study, the central concept of it, has plenty of potential; it is in the limitations of the technical skillset and an exacting time schedule that its potential has been left fully unrealized. Further research could build on Epicurean ties, and further ways to analyze inspirations to properly cover how wide a net De Rerum Natura has cast. As suggested by chapter 4, inspiration goes beyond direct quoting, and a way to search and analyze works that have drawn inspirations from something else can be difficult; unless the author claims a piece of work being influenced by something else, it is either too literary/art criticism to draw these parallels, or Academia; both resources that are heavily influenced by subjective readings of the material. However, this could allow for a study about the formation of a critical consensus regarding the interaction of Lucretius’ work and that of others. Epicurus’ importance in regards to De Rerum Natura could also be reframed from the view point of Epicurus being known through De Rerum Natura; after all, no actual works of Epicurus exist, it is only through secondary sources that his work and thoughts have been reconstructed; how much of that “reconstruction”, reinterpretation and continued importance into the 1700s are due to Lucretius?

In addition, although many conclusions based on our collected data regarding the works and graphs have been arrived at; however, there still needs further research on for example why English acted as the main language throughout the reuse works over the three hundred years? Is there any historical or social reason behind such phenomenon? What makes the reuse publications crowed in the 1700s to 1800s? Last but not least, due to the lack of time and resources, many controversial data before the 1700s hadn’t had definite answers, which led to the confusing results in a few graphs. The report is ripe for further exploration, new approaches and reinterpretations.

7. Division of work & reflections on learning

This chapter explains our division of work in the group and includes our individual reflections on learning. Our method for working as a group was dividing the tasks in two ways: some tasks were taken over by one member and some were divided between multiple members, everybody doing their part. We also helped each other whenever needed.

Hanna: I focused mostly on working with the datasets manually on the spreadsheets and with Palladio, figuring out the possible viewpoints we could approach the data from.

I have noticed I learn best when combining regular lectures and project work. I like to gain information the traditional way, like reading study materials and attending lectures. For me, processing the acquired information is easiest by working on a topic-related project. In this course, we did not have traditional lectures, so learning was mostly based on figuring out the data by ourselves with many trials and errors. Working on a project by oneself or in a group can be very helpful in the learning process, and it works best when some basic knowledge has already been achieved. What was problematic for me on this course was the lack of previous knowledge about digital linguistic research. I have previously taken the course Elements of Digital Humanities but wasn’t able to benefit from it here.

What I really liked during this course was using Palladio and examining data with it. Palladio didn’t require previous experience, and as we were provided with the correct data, it was easy to get a good look at the dataset and its details. Having very basic skills with R, I wasn’t able to create graphs from scratch, but seeing the graphs in Palladio helped to achieve a realistic perception of what the actual graphs should look like and which aspects we should focus on. Learning how to use Palladio was perhaps the most useful thing I learned during this course.

Vaishali: Responsible for data analysis, coming up with research questions, project plan, creating & giving presentations/updates, cluster analysis, and creation of the graphs for the research project.

Major part of my learning included getting started with R. From learning basics like loading a package into R to creating graphs with ggplot2, a lot of my learning came with trial and error, googling, and watching coding videos on Datacamp. Taking a data visualisation course alongside also helped immensely. Sanitising and sorting the data was one of the biggest challenges that I faced. However, it also ignited the passion to look for a solution and learn more. I also successfully acquired two Data Visualisation certifications in the process. Customising the graphs and the execution of new ideas made the data visualisation part an experience full of opportunities, growth, and learning. I also had the chance to present our progress to the class which certainly helped me polish my presentation skills. Being a part of a research group made my coordination and communication skills better. Our entire group worked as a team and wherever we got stuck, the team stayed optimistic and worked harder in the right direction.

Elli: responsible for analyzing data manually, coming up with research questions, creating the group presentation on our topic plan, and other shared tasks such as writing the report.

I personally found this course rather challenging as digital research is not something I’m familiar with and I do not think we were really taught techniques for such research during this course, because all other groups had a member already familiar with the field. I am very pleased with my group as I feel we all worked hard to get to this point, despite the number of challenges we faced. Everyone was willing to challenge themselves and learn new things in order for the group to succeed and get past difficulties. We shared all the tasks among the group as equally as possible. I personally created a presentation on our project plan at the beginning of the course and came up with our research questions with the rest of the group members. Additionally, at the beginning of the course I, among other members, organized for the group to meet up virtually a few times in order to set into action a plan we could execute. Once we finally had the data necessary for our research, we divided it equally among the members to analyze it manually. Those of us that did not work on creating graphs, myself included, analyzed more quotes than those that did, in order for the workload to be more fair. Once the data was analyzed and the graphs were ready, we began the process of writing. This again was divided among group members based on what everyone wished to work on. I wrote the introduction section as well as the section on issues and challenges our group faced. Despite each of us writing specific sections, we all added to and edited each other’s sections as well.

Henry: Responsible for a large section of the manual analysis, writing and researching the section with Epicurus, researching Milton, coming up with approaches for manual research (looking for context, etc), supporting in final presentation, writing and editing large sections of the report.

My early role in the project came in the form of researching for the background, looking for quotes in many longer texts manually (reading source materials) and trying to come up with approaches to the study. Many of the early steps and a lot of the research was scrapped as we moved into a more focused direction – much of the background ended up being immaterial. At about the midpoint of the course, we decided to settle on one specific approach, which I feel I helped to navigate. Feeling unqualified when it comes to work with Palladio, I took the largest batch of quotes for analysis and tried to set a template for how to approach the quotes. In some ways this did end up well, but I feel that different schedules that we had, even different time zones some of us were in, created some minor miscommunication, resulting in different ways of approaching the material (how the context was marked, how much was enough when it comes to covering the quotes, and so on). Finally, when it comes to the essay, my contributions range from 4.5.2 (William Willymott) to the end of 5.2 (The Qualitative analysis, which due to time restraints stayed qualitative, with very minimal number crunching), about 1/3 of 6 (Challenges and Difficulties) and the first half of 7 (Further Research), with minor additions in other chapters.

I learned a lot about time management and clarity when it comes to presenting data in group work; so much time can be wasted if things are not made clear from the get-go. As I avoided Palladio and coding, the most important things I learned have to do with experience of looking through data – in many ways I feel that this course built on my prior experience with working on corpuses.

Xinyu: Responsible for finding the assigned data regarding our research topics, helped communicate problems that the group had encountered with teachers, helpd detect overlapping clusters, and participated in making the powerpoint and writing the final report.

Through this DH course, I had a deeper understanding towards the field of digital humanities. To me it’s a field of computer science plus humanities, turning literature into quantitative and visualized data therefore audiences can have a clearer picture of the information that you are trying to convey. In this major, programming skills, particularly R and python are highly required for visualization. Although I was still a beginner of R and failed making graphs with R back then, this course got my knowledge trained and urged me to learn more about programming skills. Additionally, I learnt about data types and how to process and analyse them in a principal manner and the quantitative methodology, which is of great use in real linguistic research. I am certain that those skills learnt from the course would be helpful not only in developing my scientific thinking but also gaining practical experience. Last but not least, I learnt more about how to work efficiently in a group and negotiating with group members particularly we had changed our topics so many times until last minutes.

8. References

Wellcome Collection https://wellcomecollection.org/

ARCHER https://varieng.helsinki.fi/CoRD/corpora/ARCHER/updated%20version/archer%203_2_structure.html

Hardie, P. (1995). The Presence of Lucretius in “Paradise Lost.” Milton Quarterly, 29(1), 13–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24465286

Poole. (2018). Milton and the Making of Paradise Lost. Harvard University Press.

Seabrook, J. (2015, November 11). The Invisible Library – Can technology make the Herculaneum scrolls legible after two thousand years?. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/11/16/the-invisible-library