Contents:

- Introduction

- Distant reading Shakespeare: Our First Case, the First Folio

- Our First Case, the First Folio (page 2)

- Our First Case, the First Folio (page 3)

- Grammatical context

- Case study: Rape of Lucrece

- Observations on the Shakespearean actor network

- Conclusion & References

Grammatical context

As already mentioned, the data included some cases where Shakespeare was used in the context of English grammar. This started to intrigue us. How did a canonical playwright affect the development of English grammar decades or hundreds of years after his death?

For this part of the analysis, we ran the reuse algorithm through two more books: A Short Introduction to English Grammar: With Critical Notes (1765) by Lowth and An American selection of lessons in reading and speaking (1793) by Noah Webster.

Why them?

Robert Lowth (1710-1787) is the author of one of the most influential early grammar books. His method of teaching grammar through errors committed by ‘the best of our authors’ made grammar popular among the general public. His methods and arguments affected the evolution of grammar (Tieken-Boon van Ostade, 2010). Going through the reuse detected from Lowth’s grammar book, Biblical sources, John Stoughton, Jonathan Swift, John Milton, William Shakespeare, and Alexander Pope, in the respective order, are the most important sources upon which Lowth built his grammar.

Noah Webster (1758-1843) was an American lexicographer, author of grammar books, who also had a huge influence on American spelling . Webster was picked partly because he had a large number of Shakespeare reuses, alongside with Robert Lowth, but moreover, he could provide a different perspective on Shakespeare and grammar in contrast to Lowth.

Shakespeare reuse by Robert Lowth

The use of the ‘best authors’ as bad examples seems somewhat controversial. Shakespeare, together with other authors, was used for committing mistakes to be corrected:

However, on other occasions Shakespeare was used to support Lowth’s point:

And sometimes they were just used as an illustration:

In the last case we’re going to present, Shakespeare was mentioned to be using a different form than Lowth recommended, but it was not marked as either correct or incorrect:

As these examples show, Shakespeare’s work in grammars was used for a wider variety of purposes, not only as a bad example.

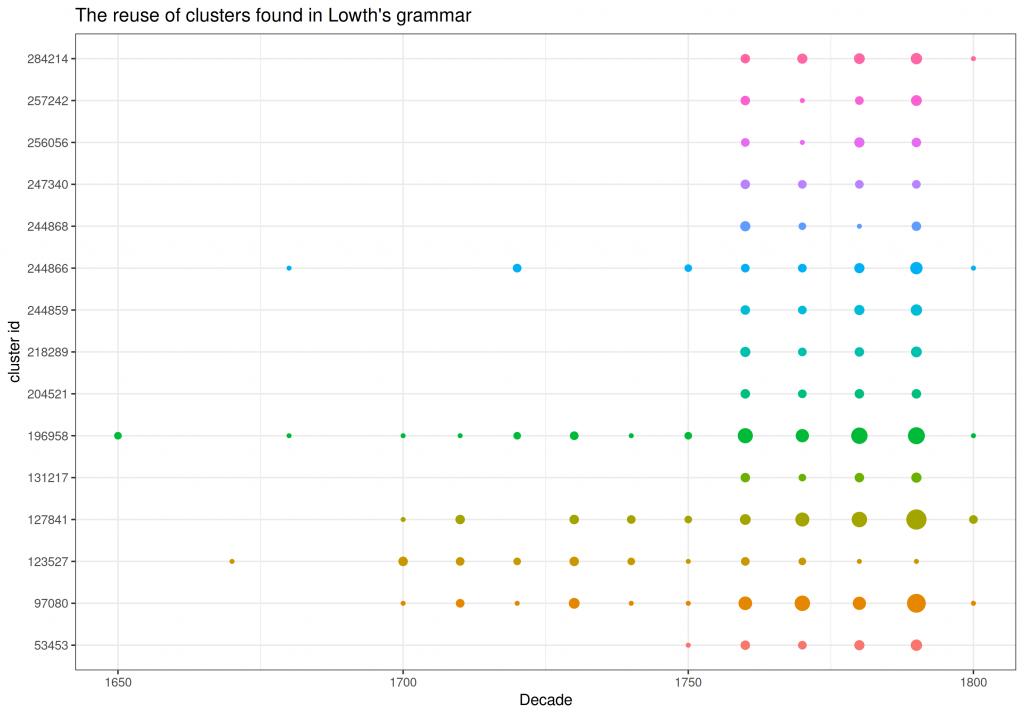

Did Lowth then change the reuse of Shakespeare? While we cannot be sure, it seems like he influenced the reuse of at least some clusters. Based on the reuse algorithm, we plotted the clusters Lowth had used in his book. As the graph shows, the reuse of these clusters increased remarkably after the 1760s when Lowth’s grammar was published. A part of this reuse is due to the reprints of Lowth’s own work, but three clusters seem to stand out from the others.

The first one (196958, in green) is from the famous balcony scene of Romeo and Juliet. Lowth (1772) uses the extract to illustrate wrong subjunctive use:

However, a part of the same scene is picked up by Henry Kames (1765) in Elements of criticism (a book including principles of rhetoric and literary appreciation targeted at American student audience) to show how “[t]he highest degree of wonder arises from unknown objects that have no analogy to any species we are acquainted with” in the comparison Romeo makes of Juliet in the so-called balcony scene, thus praising Shakespeare. The scene is now one of the most known in the whole play – probably not due to the incorrect subjunctive use!

The next cluster (127841, in moss green), coming from Measure for measure, is corrected by Lowth for the confusion of past time and participle forms (“took” instead of “taken”). The scene is also used to illustrate the morality of Shakespeare, as it discusses the human motives of mercy and justice (Griffith, 1775).

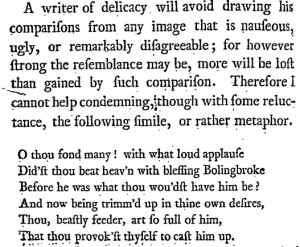

The last cluster (97080, in orange) we investigated was from Henry IV, part 2; Lowth used the exclamation “Thou fond many” to illustrate how “many” was collectively used as a substantive. The same example was later picked up by Webster. Interestingly the scene is also used in – at least – two very different ways by other authors: Elizabeth Montagu used the scene to compare Shakespeare to Greek philosophers, praising him as “one of the greatest moral Philosophers that ever lived” (1770, p. 57). In contrast, Henry Home Kames takes the scene to instruct against how one should not write (1765, p. 216):

It is hard to say a clear cause and effect in why the popularity of these clusters started to increase around the publication time of Lowth’s grammar book, but it could be assumed that the popularity of these Shakespearean plays started to increase again, and thus more and more people started to use them, Lowth among others, shaping the perception of the Bard for the contemporary audience.

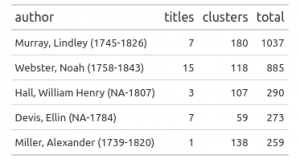

However, the greatest impact that can be directly traced back to Lowth was on the development of grammar. After the publication, with several reprints in the late 18th century, Lowth’s work was most reused by the authors in the table shown underneath. Lindley Murray and Noah Webster were influential grammarians, too, so it is relevant to study how Shakespeare was used in this context. If these authors considered Shakespeare as an important example, it indicates that Shakespeare already had a prevalent status at that time.

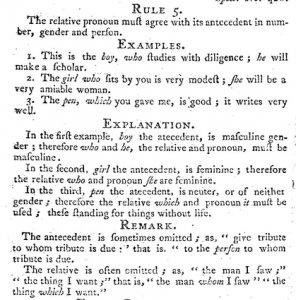

Webster takes Shakespeare to the States

Originally, we wanted to compare Lowth’s and Webster’s reuses of Shakespeare in their grammars. We created the Webster dataset from a book, that was tagged as grammar, but unfortunately only when it was too late, we found out that it was in fact not a grammar. An American selection of lessons in reading and speaking (1793) is a compilation of excerpts from various books, plays and other texts that is targeted at youth. After having a closer look at actual grammars written by Webster, we conluded, that the comparison of Shakespeare reuses we originally intended to do wouldn’t be possible because Webster mostly used pedagogical examples and he used literary works as a source of examples sparsely . For comparison, you can find a page from Webster’s and Lowth’s grammar lower. Webster’s grammar seems to be organized more pedagogically compared to Lowth’s.

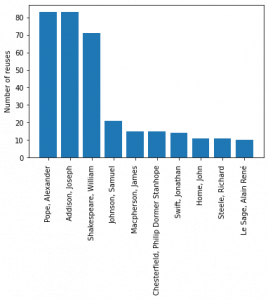

Even though we can’t compare Webster with Lowth, we still believe that Webster’s reuse of Shakespeare in our chosen title adds another important perspective to our project. Shakespere was among the most reused authors in Webster’s book, alongside Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison. Including Shakespeare and other British authors in such book of excerpts, that was intented to be read by young people, points to their cultural importance even at the time when America was in the process of building their own national identity. Furthemore, collection like this can help to futher consolidate position of these authors. Below, we can see most reused authors in the dataset generated from Webster’s work:

Reflections

Examples that we found show that even a short scene can be read and interpreted in a variety of ways. The same extract could be used to illustrate a moral message, the beauty of English language, for its rhetorical strategy or, simply, to teach grammar.

Beyond the European context, Henry Home Kames and Noah Webster discussed here were figures that influenced the teaching of English in America. The fact that they used Shakespeare to illustrate their points further suggests that Shakespeare was already back then starting to have a canonical status.