Advertisements in nineteenth century newspapers tell us about how the burgeoning press was used to sell and buy things. They tell us not only about how consumption, commerce and marketization developed in the period, but also point at cultural and technological changes in newspapers as a medium. Our research team consisting of data scientists, linguists and historians came together to the Digital Humanities Hackathon at the University of Helsinki in May 2019 to study advertisements to understand these long-term developments. We used British Library Newspapers (BLN) provided by Gale Engage as a data set to explore and analyse more detailed topics related to advertisements in the press. All images and graphs in this blogpost are drawn from the BLN.

We soon noticed that we can read advertisements closely to identify linguistic features that are typical in advertisements whose goal are to sell particular products. In order to use our data set and to identify computationally these features, we studied advertisements manually and grasped some meaningful features.

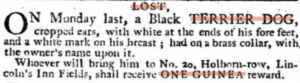

It is often hard to differentiate advertisements that are meant to sell products apart from more matter-of-fact announcements such as this ad about a missing dog:

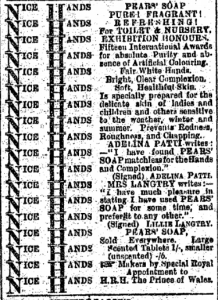

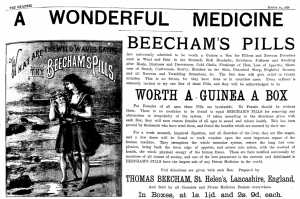

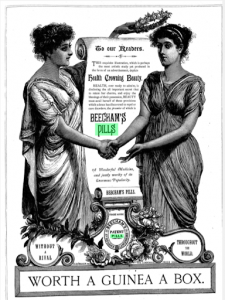

To convince readers of the benefits of a particular product, advertisements for selling products seemed to have more adjectives . The study of ads shows a number of features that seem to be typical for advertising language in the nineteenth century. This advertisement for soap in the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle from July 1886 is a good example of this.

Some of the features we find most interesting, and that we think can be quantified in a reliable way, are:

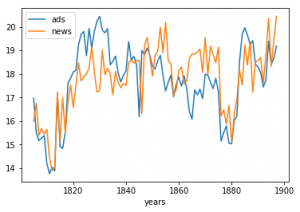

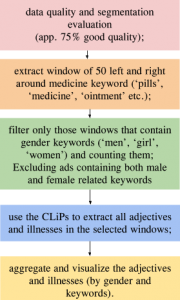

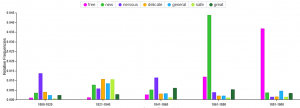

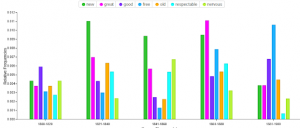

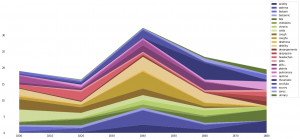

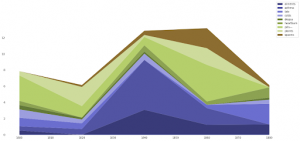

1. High levels of adjective use. We found about “absolute Purity”, “Fair White Hands” and “Bright, Clear Complexion”. But it is not only an issue of praising the qualities of the product, but (excessive) adjective use can also be used to mark possible negative consequences of not using a product or things that can be remedied by using the product. Hence we are told that the soap prevents “Redness, Roughness, and Chapping”. Earlier studies have also indicated that ads may include more adjectives than general text. A preliminary quantitative analysis does, however, not suggest that overall proportions of adjectives would be higher in advertisements compared to news text. We acquired a list of adjectives in English from WordNet and then studied the overall frequency of those adjectives in The Morning Post for advertisements and news text separately. The separation into news and advertisements builds on the article segmentation that exists in the metadata. While this metadata does include errors, we did manually evaluate its levels of precision for advertisements and found them to be on average 73 per cent up to 1830 and 87 percent for the period after 1851 (for a description see our Hackathon presentation). For The Morning Post, a conservative daily from London, the adjective share is more or less the same.

A similar plot about verbs and nouns shows that actually it is the share of verbs and nouns that is smaller in ads compared to news text. What remains to be studied if it is only particular adjectives that are more frequent in ads. Perhaps this has prompted earlier research to emphasize the role of adjectives in ads.

2. Generalizations as a way of defining the audience. Ads often define their audience by providing labels for particular groups that could benefit from a product. In this ad we found out that soap is prepared “for the delicate skin of ladies and children”. In other ads the definition of a target group may be more general, for instance by mentioning that the product is for “everyone”.

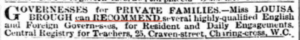

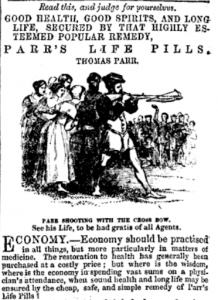

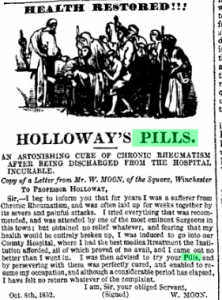

3. Quotes or expert opinion as a means to convince buyers. The soap advertisement also uses expert opinions and quotes from content customers to sell products. Both Adelina Patti and Mrs. Langtry assure any reader of the quality of Pears’ soap based on their extensive experience. Performative verbs like “assure” or “recommend” often do this kind of work in advertising texts and seem to be particularly common in certain types of ads, like job advertisements. These appear both when qualified staff is sought, but also when people with higher positions in society recommend staff for others:

A particular form of assurance are expert quotes that are used to promote certain products. These seem to have been especially important for advertisements that are related to theatre, books and other complex cultural products, and also in in the soap ad mentioned above. A quantitative analysis would allow to distinguish which products are we more likely to accompany expert statements as a way of persuading potential consumers. However, due to lacking optical character recognition quality, identifying quotes in ads was more unreliable than we had hoped for, so we decided to pursue this possibility later.

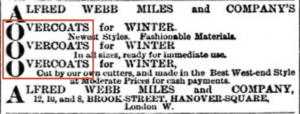

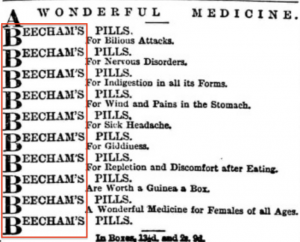

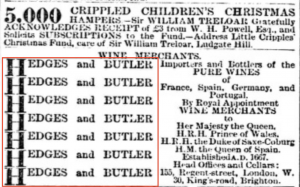

4. Repetition. Finally, advertisement text made extensive use of repetition. In the advertisement for Pears’ soap, repetition is used in two ways. First, the brand is mentioned repeatedly in the running text to remind the reader about the soap that is sold “everywhere”. Additionally, “Nice Hands” is repeated eighteen times in the left column of the ad. Here, “Nice Hands” is a selling point, but it also serves a visual purpose. The Morning Post did not include images as a way of distinguishing itself as a conservative and serious newspaper from any papers that were driven by visuals. For the ads, visual repetition like this was a way of bringing forward an ad in the midst of a whole page that might have been cluttered with small textual ads or notices.

And as a means of showing the power of repetition:

And do not forget that ads did not only repeat the same thing. Sometimes they also wrote the same thing over and over again:

Or they could include something that is is completely redundant:

Written by Hyun Jung Kang, Anna Obukhova and Jani Marjanen

Data analysis by Ruben Ros

Bibliography

Leech, Geoffrey N. (1966). English in advertising: A linguistic study of advertising in Great Britain. London: Longmans.

Gotti, Maurizio. (2005). Advertising discourse in eighteenth-century English newspapers. 10.1075/pbns.134.05got.

Lyna, Dries & Damme, Ilja Van (2009) A strategy of seduction? The role of commercial advertisements in the eighteenth-century retailing business of Antwerp, Business History, 51:1, 100-121, DOI: 10.1080/00076790802604475

Miller, George A. (1995). WordNet: A Lexical Database for English. Communications of the ACM Vol. 38, No. 11: 39–41.

Richards, Thomas. (1990). The commodity culture of Victorian England: Advertising and spectacle, 1851–1914. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bolivia Erazo did her doctoral studies in cultural history at the University of Turku, Finland. In her monograph, she examined the coming of sound cinema to Quito, Ecuador in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In general, she is interested in media history.

Bolivia Erazo did her doctoral studies in cultural history at the University of Turku, Finland. In her monograph, she examined the coming of sound cinema to Quito, Ecuador in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In general, she is interested in media history.

Axel Jean-Caurant is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of La Rochelle. His main interests concern digital humanities, word embeddings and information access. He is currently working on a project about digital newspapers.

Axel Jean-Caurant is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of La Rochelle. His main interests concern digital humanities, word embeddings and information access. He is currently working on a project about digital newspapers.

Jean-Philippe Moreux joined the BnF in 2012 as OCR and digital publishing formats expert and is now Gallica scientific advisor. In addition to being a member of the ALTO Editorial Board, he currently works on all heritage digitization programs and research projects (NLP, text and data mining, OCR, etc.) BnF participated to, as well as on the application of research results to digital libraries.

Jean-Philippe Moreux joined the BnF in 2012 as OCR and digital publishing formats expert and is now Gallica scientific advisor. In addition to being a member of the ALTO Editorial Board, he currently works on all heritage digitization programs and research projects (NLP, text and data mining, OCR, etc.) BnF participated to, as well as on the application of research results to digital libraries.