Reclaiming Mahisasura, Durga Puja, and Bengali Identity Politics

Blog post by Dheepa Sundaram

This blog post further contextualizes the talk on Durga Puja and Economic Tourism by Dheepa Sundaram, by focussing on narratives of the festival by the Asur community.

Abstract:

Durga Puja is observed in the Hindu calendar month of Ashvin, typically September or October of the Gregorian calendar, featuring elaborate temple decorations, float-like renditions of the Durga’s slaying of Mahisasura (so called pandals), scripture recitation, performance arts, processions, and idol immersions. This festival marks Durga’s battle with the shape-shifting, deceptive and powerful Mahisasura, epitomizing the victory of good over evil for Hindu communities. It is also, in part, a harvest festival that emphasizes the goddess Durga’s role as a “mother.” The Asurs, a group of tribal communities, view this holiday quite differently. Carrying the designation of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) within the Indian Constitution, Asurs inhabit certain districts in the states of Jharkhand, Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh, including the Netarhat plateau, Gumla, Latehar, Lohardaga and Palamu. The Santhal-Asurs refer to Mahisasura as “Hudur-Durga” for whom they have a special ritual involving immersion of a clay idol of their ancestor. While they do not worship Hudur-Durga, they venerate his memory as a courageous leader. The Asur communities recast Mahisasura as a storied, royal ancestor of their bloodline.

Bio:

Dheepa Sundaram is an Assistant Professor of Hinduism and Hindu Studies at the University of Denver since 2018. She holds undergraduate degrees in Comparative Literature and Religious Studies from Indiana University (2000) and a MA (2010) and Ph.D. in Comparative and World Literatures from the University of Illinois (2014) with a focus on Sanskrit and Tamil performance traditions and intersections of ritual, poetics, and politics in modern Tamil drama. Her teaching and research interests include Hindu ritual and praxis in digital contexts, Sanskrit language / aesthetics / drama, South Asian religious traditions / mythologies / literatures, South Indian performance and ritual traditions, and Postcolonial and Cultural studies. Dr. Sundaram’s current book project Globalizing Darśan: Virtual Soteriology and Hindu Branding explores the lucrative world of Hinduism online and considering the ways in which the saleability of Hinduism impact the growth of ethno-nationalist ideologies within Indian socio-political arenas.

Reclaiming Mahisasura, Durga Puja, and Bengali Identity Politics

Prof. Dr. Dheepa Sundaram, University of Denver

23 November 2020

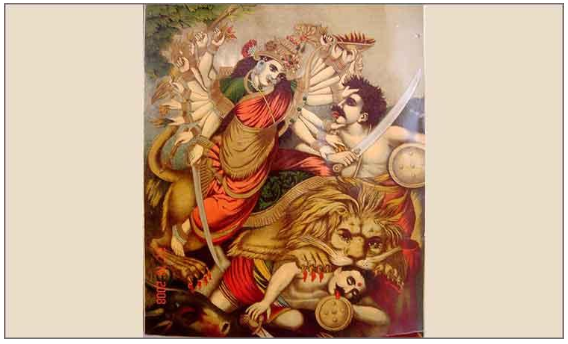

Painting of Durga killing Mahisasura and her ride the lion feasting on another asura.

Painting of Durga killing Mahisasura and her ride the lion feasting on another asura.

Credit: Google Images

Autumn in much of India signals the celebration of the Navaratri festival (nine nights of celebration of the goddess) which features goddess Durga’s defeat of Mahisasura (the buffalo-demon). Savarna or “casted” Hindu communities participate in some or all of the days of rituals and worship ceremonies coupled with food and festivities. Durga Puja is observed in the Hindu calendar month of Ashvin, typically September or October of the Gregorian calendar, featuring elaborate temple decorations, float-like renditions of the Durga’s slaying of Mahisasura (so called pandals), scripture recitation, performance arts, processions, and idol immersions. This festival marks Durga’s battle with the shape-shifting, deceptive and powerful Mahisasura, epitomizing the victory of good over evil for Hindu communities. It is also, in part, a harvest festival that emphasizes the goddess Durga’s role as a “mother.” In Bengal, the festival marks Durga’s homecoming as the state’s favored daughter. The final day of celebrations culminate with adherents carrying the colorful clay statues of Durga to a river or ocean and immersing them, signifying their farewell and her return to the divine cosmos and Mount Kailash.

The Asurs, a group of tribal communities, view this holiday quite differently. Carrying the designation of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) within the Indian Constitution, Asurs inhabit certain districts in the states of Jharkhand, Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh, including the Netarhat plateau, Gumla, Latehar, Lohardaga and Palamu. The Santhal-Asurs refer to Mahisasura as “Hudur-Durga” for whom they have a special ritual involving immersion of a clay idol of their ancestor. While they do not worship Hudur-Durga, they venerate his memory as a courageous leader. The Asur communities recast Mahisasura as a storied, royal ancestor of their bloodline whose nobility and integrity as a ruler has been deliberately misrepresented by casted Hindus during Navaratri celebrations of Durga. They offer counternarratives in which Mahisasura is deceived and murdered by Durga to appease jealous savarna deities. Many Asurs believe Mahisasura was killed by Durga during an Aryan/Brahmanical invasion in which he was outnumbered, therefore, considering it an unfair fight. In complete contrast to the Durga Puja festivities, until recently, the Asurs, fearing a repeat of the massacre their ancestral community faced at the hands of the goddess, enforced a tradition of hiding during Durga Puja festivities. Moreover, the Durga Puja period has become a period of introspection and mourning for Asur tribal groups.

Mahisasura, as depicted by the Santhal artist, Lal Ratnakar.

Mahisasura, as depicted by the Santhal artist, Lal Ratnakar.

Credit: janvikalp.wordpress.com

British Oppression and Durga Puja

There is evidence to suggest that large scale Durga Puja festivities (precursors to those that take place now) were often funded by the East India Trading Company (EITC) in British-ruled India. These were hosted for the upper caste zamindars, wealthy landlords, who in turn supported the EITC’s rule. The gentrification of Durga Puja ensured that those living on the fringes – such vulnerable tribal and disadvantaged caste communities – were further distanced from the majoritarian Hindu traditions and beliefs. Their voices were slowly diminished, their lands lost, and their culture made invisible. Ravana (King of Lanka from the epic Ramayana) and Mahabali (indigenous king celebrated during the Onam festival in Kerala who was killed by the Vamana avatara of Vishnu) are other examples of indigenous rulers that have occupied the role of “oppressor” or “evil” in Vedic/Brahmanical orthodoxy but remain heroes for those communities who claim them as ancestors.

A statue of Mahishasur as Hudur Durga in a village in Malda.

A statue of Mahishasur as Hudur Durga in a village in Malda.

Credit: Ujjwal Vishwas, 10 November 2018. https://www.forwardpress.in/2018/11/eyewitness-account-dwij-traditions-being-challenged-by-dalitbahujans-in-bengal/

Reclaiming Asur History and Mahisasura as a Hero

Asurs read the story of Durga’s birth in the prominent Sanskrit text Devi Mahatmya as a biased narrative of Asur history. In 2010, the first ever Mahisasura Memorial Day was organized in West Bengal with the assistance of organizations such as Mulnibasi Samiti and Majhi Pargana Gaonta dedicated to adivasi (tribal) cultural and social concerns (Roy 2016, 170). In the following years, student protesters at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) lobbied for Mahisasura Martyrdom Day (Roy 2016). More recently, Asur community activists such Sushma Asur and tribal historians like Vandana Tete have worked to recover Asur narratives, histories, and traditions while also seeking state recognition of Asur beliefs to combat what they see as another example of casteist oppression.

Mahishasur being worshiped in Purulia, West Bengal.

Mahishasur being worshiped in Purulia, West Bengal.

Credit Nivedita Menon. https://caravandaily.com/who-was-mahishasura-a-santhal-poet-explains/

“Amar Shaheed Mahiṣasura” – immortal martyr Mahiṣasura – was celebrated first by JNU students in Delhi in 2011 as a secular holiday symbolizing the hegemony of Brahmanical narratives within Hinduism (Roy 2016). In 2014, the organizers of the yearly event produced a pamphlet explaining their support for a holiday acknowledging Mahisasura as a great king. It described Durga Puja celebrations as “the most controversial racial festival, where a fair skinned beautiful goddess Durga is depicted brutally killing a dark-skinned native called Mahiṣasura. Mahiṣasura, a brave self-respecting leader, was tricked into marriage by the Aryans. They hired a sex worker called Durga, who enticed Mahiṣasura into marriage and killed him after nine nights of honeymooning, during sleep” (Sen 2014). This view of the Durga/Mahisasura narrative was contested vehemently by several traditional Hindu groups and conservative political figures from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

In 2016 as similar protests ensued, they prompted a police presence on JNU campus and a controversial response from Smriti Irani (BJP Human Resource and Development Minister). Irani quotes the pamphlet in a parliamentary speech shortly after the event suggesting it indicates a “depraved mentality” and that these students should be severely censured for their dangerous “anti-national” statements. Op-eds and blog posts linking the authors of the pamphlet to radical “communist” groups or craven political motivations spearheaded a state-sponsored effort to delegitimize these narratives by discrediting the sources. Organized by the JNU All India Backward Students’ Forum (AIBSF), Anil, a student leader of the group pushed back on these attacks, detailing how students “were celebrating Mahiṣasura Martyrdom Day because he [was] an icon for the adivasis and other marginalised people in India” (Sen 2014). He went on to lament that one could not dishonor the citizens in this way since it was against the Indian Constitution (Sen 2014). In other words, the holiday was both recognition of Mahisasura’s sacred stature within Asur communities while also decrying oppressive conditions of caste inequality that continue to roil modern Indian society.

Though beginning as a fight for recognition of tribal traditions and beliefs, celebration of Mahisasura and marking his death as a martyr is grounded in exposing casteist beliefs and oppressive savarna traditions that elide alternative and minoritarian rituals. deities, and traditions in India. By reclaiming Mahisasura as a hero, Asurs excavate what they see as a stolen history and ensure that their competing narrative can find expression alongside Durga Puja celebrations. Indeed, as Anil notes, “no one says you shouldn’t worship Durga…But why must you show Mahisasura dying?” (Sen 2014). In essence, the alternative holiday attempts to find a place for the Asurs within the Navaratri celebrations. It does so by marking their quest for recognition of their ancestor as simultaneously a protest by adivasi communities against the social, cultural, and economic inequities that continue to plague disadvantaged castes and tribal communities under the guise of religious belief and tradition.

Works Cited

Roy, I. 2016. Transformative Politics and the Imagination of Mulnibasi in Bengal. In: Chandra, U., Heierstad, G. and Nielsen, K. B., eds., The Politics of Caste in West Bengal. London and New York: Routledge.

Sen, J., 2014. Mahisasura and the Minister. The Wire, [online] 27 Feb. Available at https://thewire.in/politics/mahishasura-and-the-minister, accessed 20 August 2019.

Suggested Readings

Kostka, I., Kumar, P., eds., 2016. The Case for Bahujan Literature. New Delhi: Forward Press Books.

Kumar, P., ed., 2016. Mahisasura: A People’s Hero. New Delhi: Forward Press Books.

Ali, A. 2015. A Study on Asur Community: A Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group – Its Origin, Culture and Social Status. Zenith International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 5(7), 93-99.