Author: Kathlyn Elliott, PhD researcher, Fulbright-EDUFI Fellow 2021-2022 at University of Helsinki, Drexel University.

Future Challenges in Education: Ontological/Epistemological, Methodological, and Challenges of Practice

Abstract

In this paper, I share my reflections on the challenges that face the future of education globally. Through content analysis, I analyze the challenges that this course highlighted into ontological/epistemological challenges, methodological challenges and challenges of practice. In each section, I highlight trends that were explicitly discussed in the lecture series and some which were alluded to but perhaps not as explicitly engaged with. By exploring these challenges, we are able to see how certain themes like individualism or truth show up throughout the different categories.

Introduction

In signing up for this course, I was not entirely sure what to expect. The summer prior to applying to PhD program I had attended a course offered by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the professor who recommended it suggested I look at the work by Gita Steiner-Khamsi on the Mongolian education system. I then read and used more of her articles in my first semester of my doctoral program, and it was for that reason that I signed up for the course. As the course began, I was hoping for guidance from these big-name experts about what the future of education could and should look like. However, as is often the case, I am left with far more questions than I started with, and both questions that tie to my own research agenda on the use of education to prevent violent extremism as well as more general questions about the nature of education. Throughout the course I found myself thinking continuously about the challenges both new and old that face education. In this essay, I organize these challenges by type: ontological and epistemological challenges, methodological challenges, and challenges of practice. This organization allows for both the complexity of the different levels of challenges, and also allows for illustration of how challenges at different levels build on each other.

Literature Review

Social Role of Education

Education is defined broadly as any type of formal or informal program that is used to instruct. This includes traditional education that happens in P-20 institutions in formal classroom instruction as well as programs implemented by civil society organizations. Within these systems, teachers are the daily workers implementing these systemic policies. In general, curricular approaches span a wide range of different approaches and understandings; while traditionally curriculum was understood to mean subject matter content, it now also can include skills, like 21st Century Skills or social emotional skills. In the same vein, pedagogical also varies from school to school and classroom to classroom depending on the expectations of the school system and teacher within said system. Niemi et al. (2018) argues, specifically in the Finnish context but broadly applicable to all contexts that analyzing pedagogy allows for better understanding of the hidden curriculum. Pedagogy helps socialize students for the expectations of what it means to be a member of society, and it’s not always as straightforward as curriculum can be (Niemi et al., 2018). Bush and Salatarelli (2000) argue there are two faces to education – education as a driver of peace and education as a driver of conflict. Metro (2020) adds a third face of education, education that provides a neutral impact or a complex one.

Role of Teachers

Teachers are central to all educational systems and have an immediate and large impact on the beliefs of students. After parents, teachers are some of the largest influences in students’ lives. Scholars such as Freire (1968) highlight the agentic role that teachers play through their choice of pedagogy, while others argue that schools are sites of production and reproduction (Apple, 1995; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). Education has also been conceptualized as a feminized space (Apple, 1995; Luttrell, 1997). Historically formal education has been concerned with preparing young people for the workforce and to be good citizens. What is deemed acceptable by society shifts over time and therefore both school policies and national policies reflect those changes. Educators however are called upon to implement these changing norms in varying contexts. In the Finnish context, Rissanen et al. (2018) argue that teachers take on the responsibility for students’ moral development, and that teacher’s implicit moral theories end up playing a role in how they interact with students and contribute to their moral development. Based on Lipsky’s (2010) street level policy bureaucrat, Arnold (2015) argues that street level policy entrepreneurs, which Sadan and Alkaher (2020) interprets as teachers, as being under researched policy implementers. In the Finnish system teachers and administrators are the ones who make decisions about curriculum and pedagogy. They are given a great deal of professional discretion in the implementation of national policies. Generally, teachers are responsible for using their professional discretion to implement policies which designed to encourage learning.

Education in the International System

Similarly, education has been central to the work of the United Nations and other international bodies since their inception. China and Latin American nations pushed for education to be specifically elucidated in the UN Charter (Jones & Coleman, 2005). Initially the push for education was focused on gaining skills to enter the modern economy and bringing formerly colonized nations into the global economy based on arguments from human capital theory (Chabbott, 2003). Over the next two decades, this perspective developed into the modernization narrative that is so familiar in our current world – individuals need skills, mindsets, and values to engage in our modern world and economy. In the 1970’s, critical theorists began to push back on these narratives of the modernist definitions of education and

argued for an approach to education that looked to bring alleviation to suffering (Chabbott, 2003). The 1980’s saw the rise of the World Bank’s influence in global education funding and, in particular, it’s structural adjustment policies (Jones & Coleman, 2005; Chabbott, 2003). It was only in the 1990’s and the focus on Education For All, that women became the particular focus of education for development (Chabbott, 2003). Women have often also been central to the provision of education due to the gender nature of carework, in which educating children is viewed as women’s work (Apple, 1995).

Modernization Theory in Education

Modernization theory as defined by Fagerlind and Saha (1989) developed out of World Wars I and II and its focus was inherently optimistic. The theory states that over time countries become more modern as they adopt modern institutions, values, and behavior which all lead to economic development (Fagerlind & Saha, 1989). Modernization theory was particularly concerned with helping current and former colonies “catch up” with the industrialized West both in technology and norms and values. Education is viewed by modernization theorists as central to creating these skills as well as new values and behavior, and, in time, economic development. Therefore, governments were encouraged to spend on education as it was deemed crucial to their economic success. The Heyneman-Loxley effect illustrates that very issue by showing that in low GDP nations, government spending on education has more impact on student achievement than family socioeconomic status (Baker, 2002).

Critical Theory in Education

In opposition to Modernization theory, critical scholars have a more nuanced view of the complex role that education plays in society. For them, education is often thought of as a tool of reproduction of society, especially the hierarchy that currently exists in society. Functionalists like Emile Durkheim, Talcott Parsons and Robert Merton agree that schools are primarily responsible for perpetuating the accepted culture and that it is their rightful and correct responsibility to reproduce said culture (DeMarrias & Lecompte, 1999). Bourdieu & Passeron (1990), on the other hand state that social and cultural capital are reproduced through schools critique both the role that schools play and the culture they reproduce. Neither of these groups ascribe high levels of agency to schools to change the status quo, however, both Dewey (1938) and Freire (1968) conceptualize education as a way to create a society that is prepared to engage and change the world as it is, diverging from simple reproduction. While the particulars of

Dewey and Freire’s theories are quite different, there are many similarities in that they see education as positive force for creation.

Neoliberal Theory in Education

While neoliberalism and modernism are often thought of as having similar goals, the difference is how the view of the state and of business. Neoliberalism is an economic theory that limits government spending in favor of market driven reforms. Colclough (1996) explains that neoliberal theorists believe three key ideas: that governments are not willing or able to fix things, the public sector is underfunded, and that the existing resources are misallocated. Supporters of neoliberalism believe that the free market will better, more efficiently provide for the needs of the people globally through the shrinking of the public sector, limiting government intervention in the economy, and deregulating the markets (Torres, 2002). In terms of education, Torres (2002) argues that the policy preferences of the World Bank interpret neoliberal reforms to focus on two areas: privatization and the reduction of public spending. Privatization has the dual goal of reducing public spending and stimulating the markets. This diverges sharply from Modernization theory which argues that the state has a deeply vested interest in being directly involved and responsible for education. Colclough (1996) points to four key tools that are used by neoliberal reforms in education: user fees, student loans, private schools, and redistribution of savings to parts of the education system which are most socially beneficial. This approach was extremely popular in policy implemented in the Global South during the 1980’s and 1990’s but continues to be felt in all nations today.

Research Question

In order to best address the topics that were discussed in the course over the semester, I designed a research question: What challenges face education moving into the future?

Methodology

To answer the question, I designed a study using both a selection of articles, and analysis of notes I took during the seminar talks. I used the course documents provided as required reading, and added readings that I had previously done, as well as conducting a brief Google Search. Then I coded both the documents and my notes looking for trends using content analysis (Krippendorff, 2013). This section will discuss data collection and methods, data analysis, limitations, and positionality.

Data Collection and Methods

In selecting items for analysis, I pulled peer-reviewed documents in three different ways. The first set of documents included the four which were included in our course syllabus. I then pulled articles that I had previously read which aligned with the topics discussed. Finally, I searched I using Google Scholar for “post-truth” and selected articles that focused on education. While quotes are included here to demonstrate the full phrase they were not employed in the actual searches. These searches returned hundreds of thousands of articles. The researcher then chose a total of 2 items based for inclusion based on the number of citations, quick reading of title and abstract. In addition to these documents, I also included my notes from the presentations that corresponded with the readings we did in class.

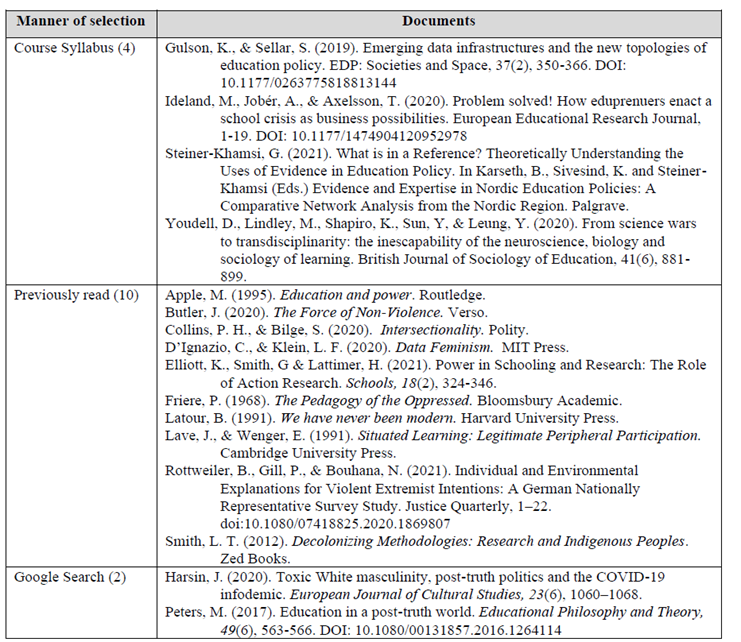

Table 1 Literature Reviewed and Source

Data Analysis

N’Vivo software was used for all stages of coding with all data and analytical memos uploaded to the platform. The first-round coding was Concept Coding which assigns macro level concepts to data analysis in progress (Saldaña, 2016). In particular, the researcher was looking to code the concepts of challenges or problems. During the second round of coding, the researcher focused coding on the types of problems that were discovered in the first round. Second-round coding used Pattern Coding to break the larger concepts into smaller groupings; this is often used to demonstrate emergent themes (Saldaña, 2016). From this round, emergent themes emerged as challenges of ontology and epistemology, challenges of methodology and challenges of practice.

Limitations

All research contains limiting factors, and this research is no acceptation. This research is limited by the fact that only peer-reviewed journals were used; this does not allow for potential input by teachers, students and parents, but rather focuses on how educational researchers perceive the problems facing education. Additionally, this research was limited by the time frame and vast amount of potential problems that have come to light with the coronavirus pandemic. Similarly, this seminar was done virtually with academics primarily from the Global North which means that the concerns of those educational researchers and practitioners in the Global South may have been overlooked as well.

Positionality

It is important as a researcher to disclose my positionality to acknowledge and minimize any bias present in my work. I am a white woman, upper middle class, who was educated at private institutions from pre-K through my doctoral program. While my education was similar in that all institutions were private, they were in vastly different contexts, and different countries as my family, and then myself moved every five years, if not more frequently. They all also had vastly different goals and missions. As a former high school social studies teacher, I have taught at two private schools and one charter school. I am aware of the ways in which education has changed over the past ten years because I lived through many of those changes. I know how the conversations are similar and different across different spaces and contexts. I consider myself to be a critical pragmatist and acknowledging that is important to laying out how I understand the challenges facing education. I feel that the paradigm wars are exclusionary and seeking to create a hierarchical system out of research paradigms, which is both problematic and irrelevant. To me the goal of research is to help understand the reality of our world, and to make it better for as many people as possible, and therefore arguing about which type of research is better or more real, feels a waste of time.

Future Challenges to Education

Epistemological/Ontological Challenges

Ontological and epistemological challenges deal with issues of what is knowable, what exists, the role of material objects in observable reality, and whether or not all things have the same level of beingness. The ontological and epistemological challenges that face education are great. They include beliefs that all things are quantifiable, questions of what type of knowledge counts, and a growing skepticism of fact. These ontological and epistemological issues continued to reappear throughout the course and in discussions of the future of education.

The first challenge that is presented is the belief that everything is quantifiable which epistemologically presents a challenge. In my own research on the prevention of violent extremism this comes up often. How do we measure and quantify a prevented extremist attack? How do we measure and quantify an individual who did not become an extremist? While I appreciate and embrace the continued work to create larger data sets and measures that more precisely share different aspects of our world, I think that pretending that the entire world is quantifiable is misleading. This acknowledgement of spaces that are unquantifiable are primarily thought to be the space of qualitative researchers, but I believe quantitative researchers have a role to play in this discussion as well. To divide these unexplored and unmapped spaces is to continue the Paradigm Wars, which hopefully are far behind us. Youdell et al. (2020) makes reference to the Paradigm Wars in their article, and while I appreciate the struggle that those who came before us went through, I also think that the tension between quantitative and qualitative research is misleading. Latour (1991) in his influential work, We Have Never Been Modern, argues that the scientific paradigm based in Enlightenment thinking is itself a man-made creation and is no more empirical and logical than other systems of belief. One is the problems of modernization as a movement in education and especially in global education where Western nations impose certain narratives about what progress is and looks like. Latour’s (1991) comparison of Boyle and Hobbes was effective in proving his point that modernism has allowed for the creation of the scientific and the natural worlds as totally separate and not related, when

in fact they are completely dependent on each other. As a critical pragmatist, I would argue that perhaps the Paradigm Wars create a false dichotomy in the identity of the researcher. Instead, different questions necessitate the use of different ontological lens, and that most of the world is in the middle, which is actually very similar to Latour’s concept of the Middle Kingdom which refers to modernity’s eschewal of mediation between the different paradigms (Latour, 1991).

This brings us to the second challenge facing the future of education, the need for indigenization of knowledge. The challenge is that we as a modern society need to find ways to regain indigenous ways of knowing and recognize them as legitimate, without recolonizing those societies again, while bringing indigenous knowledge to non-indigenous communities. Smith (2012) argues that research historically has been a Western concept and argues that research needs to shift in order to become an indigenous and Southern concept and practice. In particular the emphasis on the individual in the process of coming up with research concepts and implementing research is central to the current model of research and is something I will return to later in both methodological and practice-based problems as well. Smith (2012) makes extremely powerful arguments for why we are not really post-colonial, an argument that resonates to varying degrees depending on the specific local context. In her book, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Smith shares a Bobbi Sykes quote “What? Post-colonialism? Have they left?” (Smith, 2012, p.25) as a reminder that in places like the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, we are not living in a post-colonial world. We are still living in a colonized and settled world. In places like India, and nations like Nigeria and Algeria, there are still long-lasting impacts from colonialism, but the colonizers physically are no longer there. Smith also uses the Fanon quote “Decolonization which sets out to change the order of the world is, obviously, a programme of complete disorder” (Smith, 2012, p.28). This emphasizes that while we thought at one point that the decolonial project was at simply trading colonial governments for national ones, the impacts of colonization are deeper and will take far longer to undo if they even can ever be undone. I think of Hong Kong here, and the current protests for democracy; is China, by trying to crush these democratic protesters, effectively wiping out the remnants of British colonization? Should we be praising this choice as a former colonized nation regaining control and implementing more authentic government? I use these examples because they resonate with me personally. I am American and constantly reminded of the white settler colonization while teacher American history and living in the US. Similarly, I lived in both Hong Kong and China, and those questions about colonization, nationalism and democracy are inherently intertwined. I am still trying to understand how Finland’s history of colonization by both Sweden and Russia, and their own colonization of the Sámi people impacts both their national narrative, conceptualization of knowledge and understanding of decolonization. As an outsider, I am not sure that I know enough yet to comment, but I am continually asking friends and colleagues about this topic.

The third challenge that faces education is the conceptualization of the individual, societal and material reality. Youdell et al. (2020) discuss the changing transdisciplinary nature of education research, and in their article they speak of assemblages. This begs the question of what education research uses as its base category – should we focus on individuals, or should we look at assemblages as systems that allow for situated learning to take place in a very specific context? I think the argument for moving towards assemblages is powerful, popular and problematic. It is powerful because of the acknowledgement that humans are not isolated and that other factors play a role in our learning. It is popular due to the rise of post-humanism and the move to decenter the human, especially when tied to environmental progress. The problems come from the idea within assemblages that all entities contain the same level of beingness. This flat ontology is problematic especially for those of us in the Global North who argue that certain non-human objects hold the equivalent power and beingness to humanity, when many others would argue that in other spaces certain human lives are hardly valued at all (think Dalits in India, women in Afghanistan, etc.). While this is obviously a broad argument, I do think we as researchers must proceed with caution assigning non-human entities the same “moral equivalence” as humans, when many humans themselves are not treated or considered as fully human. There is a need for a new generation of philosophers to detangle or re-tangle our ontology in a manner that allows for value and beingness in all living and created things while still allowing for humans to hold a separate category.

The final ontological and epistemological challenge facing education is the rise of the post-truth movement. I will speak only briefly on this here, and develop these ontological arguments more in another article, and more here in the section on the problems of practice, but the current political climate returns us to Latour’s (1991) argument that the modern, empirical world we live in is a human construction. Both the humanness of this construction and the constructed nature are increasingly visible with the rise of vaccine skepticism, Q-Anon, and other such nonsense.

Methodological Challenges

The methodological challenges to a degree grow out of the epistemological and ontological challenges presented in the section above. In particular the challenges of quantification appear again in methodological challenges as well as the focus on individualism. However, in addition, I also add one additional challenge that I see, the ongoing challenge of critical scholarship.

Methodologically, the individual remains the focus of education research. We seek to understand how individuals, or groups of individuals respond/learn/change. Even in Youdell et al. (2020), where they focus on assemblages, we are looking at the impact of a system (location, others, etc) on an individual within that system. This is a first step; however, as Smith (2021) argues, and Butler (2020) reiterates, the concept of the individual as separate from the community is a creation of Western Enlightenment thought. For Butler (2020) individual in theory and philosophy is conceptualized as a self-sufficient adult male, when in fact they did not come into existence premade and fully adult. They were born and raised by others. It begs the question of who is the individual that we conceptualize in educational research? How often do we consider the family, community, context, not just in understanding the backdrop for research, but including it as part of what is measured? Rottweiler et al. (2021) argue that environmental variables are a significant factor in individuals’ engagement with violent extremism, and we are seeing increasing evidence of that shows individuals are impacted positively by their neighborhood (Bergman et al., 2020). We are optimizing everything for the individual learner, but if learning happens in community should we not be focused on different metrics when assessing? Situated learning is not a new theory, yet the neoliberal emphasis on the individual often overrides what is not new theory (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Instead, there is the promise that this individual data can be used to serve marginalized populations better.

This leads to the second challenge presented when considering the future of education, the increasing datafication and automation of work. There is significant potential power that datafication and quantitative information can show how to make significant changes to society. D’Ignazio and Klein (2020) arguing the power that quantitative data has to illuminate those who have been hidden. D’Ignazio & Klein (2020) provide steps to do this work in the book Data Feminism: collect, analyze, imagine and teach. In particular, collect focuses on compiling counterdata and is especially meaningful because it highlights what is often overlooked in empirical research – that there is data that is not being collected or measured. This premise is powerful, and constantly requires us to ask “What is missing? Why?”. Often those missing areas end up being places where multiple vulnerabilities coexist, as highlighted in Collins & Bilge (2020). This process also increases the rigor of research in that we are looking for the gaps that have been ignored and the data that has not been collected. Our assumptions that datasets provide the complete picture is a huge blind-spot, one that we are especially susceptible to in the modern world. Gulson and Sellar (2019) similarly address the automation and quantification of data in their article and argue that this creates new spaces and new opportunities for critical approaches. However, the article acknowledges, as Seller did in his talk as part of this course (Sellar, 2021), that they have yet to use this data in a critical fashion. While datafication and increased quantification of reality does hold the potential to solve problems, we are continually failing to figure out how to do this in practice. Similar problems present themself in policy as well. Steiner-Khamsi (2021) discusses the plethora of data public policy, especially the highly cited, data heavy quantifiable sources like OECD. This use of data in policy mirrors what I discuss in an article out this fall (Elliott et al., 2021). The datafication of education acts as a form of social control, illustrating Foucault’s use of Bentham’s panopticon, with the increasing about of data collected provided more and more data points that educators and students can be assessed on (Elliott et al., 2021). Is all of this data creating new knowledge or is it simply creating new challenges of data management and privacy? Having more data in existence does not solve the problem for us; we need to be more intentional about what types of data we collect in order to be able to use data to solve new challenges.

The final challenge facing the future of education methodologically is that of the critical scholars. Critical theory is not new in education, and if it is traced it back to Marx and Engels it is quite old. Yet, many of the battles fought by critical theorists appear to be reappearing in the public space, in true dialectical fashion. This begs the question, if critical theory fails to successfully address the problems it hopes to address, what is the role of critical scholars and researchers? In my view, critical scholars and researchers have been much like the vanguard of the Soviet Revolution, in theory leading the way, but if people are not following, not really going anywhere. This is where Smith’s (2012) exhortation towards more collaboration, especially with practitioners becomes even more important. Specifically, Elliott et al. (2021) call for broadening how research is conceptualized within the academy to include action research and research that practitioners such as teachers and counselors are engaged in. Without new perspectives, new placements within the field, how else are we going to both be able to measure the information that is missing, and be able to implement the necessary changes?

Challenges of Practice

In this last section, I turn to the challenges of practice that are facing the future of education. I begin with again looking at the neoliberal turn in education, both the privatization of educational actors and the way it impacts education. This includes the ongoing discussion of the challenges for teachers in the workforce, as well as issues of data privacy. The second challenge here is the one posed by the ongoing move to internationalize education and the impact of “reference societies”. Finally, I want to return to a discussion of the rise in authoritarianism and reactionaryism in the context of practice.

Neoliberal education policies continue to abound, even after we have seen the results of the SAP policies of the 1980’s and 1990’s. In many contexts, cuts in government spending leads to opportunities for edu-businesses to flourish. Hinke Dobrochinski Candido (2021) highlights the romanticization of the neoliberal approaches to education especially by those who are not embedded in the classroom. Ideland et al. (2000) highlight this in their article in Sweden. In Sweden, problems with the educational system have become big business for edu-preneurs. With these changes, we see businesses simplifying problems and answers for profit, especially when it comes to teacher training. This new private-public state-work illustrates one way in which neoliberal policies impact education practice. Neoliberal policies are also seen in the drive to ensure that students exit school workforce ready. Apple (1995) implied that the responsiveness to the workforce is part of the increased control that both the state and the capitalist economic system exert over education. He also categorizes how that control is exerted (simple, technical, and bureaucratic) (Apple, 1995), with a focus on control of curriculum and workforce readiness falling under technical control. As a classroom teacher for ten years prior to starting my PhD, I have also found bureaucratic control to be problematic. Whether it is maintaining your teaching credential, or managing sick time, or lack of a transparent pay scale, often the challenges I encountered fell more in the bureaucratic area. At the same time, teachers are increasingly being blamed for the failure of schools. Antti Saari also made this point in his final presentation on the panel (Saari, 2021). While he makes a valid point that some teachers, both older and younger, as hesitant to move away from the teacher centered classroom, I think blaming teachers misses the point. Why are teachers resistant? Perhaps this is resistance against the deskilling of the profession, and perhaps it is simply they are tired of the constant innovation. It could also be that there are tons of competing requests being put on teachers who must navigate often contradictory demands (Lipsky, 2010). While neoliberal capitalism values efficiency and innovation over all other things, it is quite possible that this conflicts with what research shows is a good education. The rise of neoliberal policies has also provided new opportunities for making money off of all the data we now collect. We see more and more edu-businesses contracting and subcontracting labor out, which leads to greater opportunities to sell data collected as an additional way to make a profit (Gulson & Sellar, 2019).

Another is the deskilling of teachers, where we see curriculum and standards developed not by teachers and educators but by those outside of the profession, whether policy makers or edupreneurs. Apple (1995) highlighted this challenge 25 years ago, but the problem continues to be exacerbated by new technologies which simplify transfers of policies. The challenges of policy transfer also show up in Steiner-Khamsi’s (2021) on reference societies. While nations like Finland and Singapore often are used as examples for their high PISA scores, there are problems when education policies are taken out of context. For one, often the policies do not smoothly transfer or have the same effect because the national context is so central to its success. Similarly, these reference societies also may suffer from the model minority challenge, where when they fall short of expected outcomes there is a great deal of shame. In fact, in a conversation I was having with a colleague recently, he argued that perhaps there was a connect with the achievement of high PISA scores and a society based on shame to begin with. Hinke Dobrochinski Candido (2021) also problematizes the neocolonial nature of Finnish educational exports both from the nations that export their models, and from the countries that import educational models. She specifically cites Brazil and Finland’s relationship around educational pedagogy, which both illuminates the tension between Global North and Global South, but also ironically ignores Brazils’ deep history as an educational leader based on the Freirean model of Educação do Campo used by the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement (MST) highlighted by Tarlau (2015).

In addition to all the challenges of neoliberalism and individualism, there is also a current trend towards reactionaryism. This trend shows itself in an increasing tolerance for authoritarianism and illiberal governments, as well as a “post-truth” mindset that questions science and factual research. Not only does this movement pose an existential threat for society, but it also makes the work of educators even more important during a time when teachers are already overburdened and underappreciated. While there has been an uptick in focus on 21st Century Skills such as media literacy and critical thinking, all of this is happening too late for the adults who have already left school without these skills who are making decisions. It is often men, working class, and older, in areas that are being deindustrialized whom seem to be the most vulnerable to these messages of anti-immigration, anti-democratic, anti-vaccine mania (Peters, 2017). Harsin (2020) refers to it as emo-truth “Emo-truth is a particular form of aggressive masculine performance of trustworthiness, corresponding to a code for recognizing it, resulting in a legitimated status of the popular truth-teller, and at odds with more official scientific, institutional truth-tellers.” Both the election of Trump and Brexit in 2016 signaled this shift was well underway, and five years later we are no closer to understanding or stemming the tide from which it comes. The anti-mask/anti-vax phenomenon brings together not only distrust of traditional authorities, but toxic masculinity, racial prejudice, and rampantly selfish individualism (Harsin, 2020). Hinke Dobrochinski Candido (2021) ties this to current problems in education research as well, where there is fabrication of data and evidence. Teachers have come under attack for their role in instructing students on facts and truth. Consider the current uproar in the United States about the role of critical race theory in K-12 education. As a World and American history teacher for ten years, I can attest that I never taught critical race theory to students. As an educator, I was however taught to understand how using critical race theory in my pedagogical approach, can help teach history in a way that is truer. This truer version of history is more complex and lacks tight narratives of triumph and destiny, and often exposes the hard choices individuals and societies make in difficult situations. It’s not pretty, romantic, or grand, but it is human. It helps students understand that while it often feels like we are living through unprecedented times, all humans faced difficult decisions. Those who want to be post-truth want the myth rather than the messy truth. In fact, Freire (1968) warns us of these very trends. He talks about sectarianism as castrating, mythologizing, and alienating, and radicalization as demythologizing, engaging and creating (Freire, 1968). Obviously Freire (1968) is speaking narrowly about radicalization as leftist radicalization, but his point that mythologizing is connected with feelings of castration and alienation are accurate, and he proposes that the opposite of that is engaging and creating.

Conclusion

While it is clear that many problems face the future of education, I have organized them here by ontological/epistemic problems, methodological problem and problems of practice in part to highlight the intertwined and buildable nature of many of these problems, but that specific aspects fit more clearly into certain categorizations. While technology has certainly provided a significant number of potential solutions, much like any tool, it is not inherently positive. I think that is a mistake that we have made over the past two decades in part because of the entrenched neoliberal and modernist mindsets of many individuals in many positions of power. The new coverage of Facebook and other social media platforms over the past five years, has seemed to finally shake loose some concessions that perhaps technology is not inherently positive.

Similarly, the big questions and challenges that face society does not seem to change much either. What counts as knowledge? Who counts when we measure? How do we use education to improve society? What are the limits of what a good education can do to improve society? How do we empower those without power to participate in decision making? I know that these questions can often feel overwhelming and too big to ever address, but the large ontological and epistemological questions must guide our work with both the methodological challenges and challenges of practice as well, otherwise we continue to use small band-aids without ever addressing the larger question. I am reminded of a question that was asked of Hinke Dobrochinski Candido (2021) at the end of her summary by an Egyptian academic working in the US. Her questions about the intersection of the theoretical to her own lived experience was exactly what we often need to be reminded of as academics. Our work is about people’s lived experiences, and we cannot separate the two, even though the academy and the Ivory Tower try to insist that there is little place for practical research in universities.

References

Apple, M. (1995). Education and power. Routledge.

Arnold, G. (2015). Street-Level Policy Entrepreneurship. Public Management Review, 17(3), 307–327.

Baker, D., Goesling, B. & Letendre, G. (2002). Socioeconomic Status, School Quality, and National Economic Development: A Cross-national Analysis of the “Heyneman-Loxley” Effect on Mathematics and Science Achievement. Comparative Education Review, 46(3), 291-312.

Bergman, P., Chetty, R., Deluca, S., Hendren, N., Katz, L., & Palmer, C. (2020). Creating Moves to Opportunity: Experimental Evidence on Barriers to Neighborhood Choice. American Economic Review. NBER Working Paper No. 26164. https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/cmto_paper.pdf

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1977). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Sage.

Bush, K. D., & Saltarelli, D. (2000). The two faces of education in ethnic conflict. Retrieved from http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/insight4.pdf

Butler, J. (2020). The Force of Non-Violence. Verso.

Chabbott, C. (2003). Constructing education for development: International organizations and education for all. Routledge.

Colclough, C. (1996). Education and the Market: Which Parts of the Neoliberal Solution are Correct?. World Development, 24(4), 589-610.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality. Polity.

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020). Data Feminism. MIT Press.

DeMarrias, K., & LeComte, M. (1999). The Way Schools Work: A Sociological Analysis of Education. Longman.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. Touchstone.

Elliott, K., Smith, G & Lattimer, H. (2021). Power in Schooling and Research: The Role of Action Research. Schools, 18(2), 324-346.

Fagerlind, I., & Saha, L. (1989). Education and National Development (3-64). Oxford, United Kingdom: Butterworth Heinemann.

Friere, P. (1968). The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic.

Gulson, K., & Sellar, S. (2019). Emerging data infrastructures and the new topologies of education policy. EDP: Societies and Space, 37(2), 350-366. DOI: 10.1177/0263775818813144

Harsin, J. (2020). Toxic White masculinity, post-truth politics and the COVID-19 infodemic. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(6), 1060–1068.

Hinke Dobrochinski Candido, H. (2021, December 10). Reflecting on the Future of Education. “Future of Education – to whom and for what?”. FuturEducation, Helsinki, Finland.

Ideland, M., Jobér, A., & Axelsson, T. (2020). Problem solved! How eduprenuers enact a school crisis as business possibilities. European Educational Research Journal, 1-19. DOI: 10.1177/1474904120952978

Jones, P., & Coleman, D. (2005). The United Nations and education: Multilateralism, development and globalization. Routledge Falmer.

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Sage.

Latour, B. (1991). We have never been modern. Harvard University Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individuals in Public Services. Russell Sage Foundation.

Luttrell, W. (1997). School-smart and Mother-wise: Working Class Women’s Identity and Schooling. Routledge.

Metro, R. (2020). The third face of education: Moving beyond the good/bad binary in conflict and post-conflict societies. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 50(2), 294–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1657317

Niemi, P., Benjamin, S., Kuusisto, A., & Gearon, L. (2018). How and why education counters ideological extremism in Finland. Religions, 9, 420.

Peters, M. (2017). Education in a post-truth world. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(6), 563-566. DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2016.1264114

Rissanen, I., Kuusisto, E., Hanhimäki, E., & Tirri, K. (2018). The implications of teachers’ implicit theories for moral education: A case study from Finland. Journal of Moral Education, 47(1), 63-77.

Rottweiler, B., Gill, P., & Bouhana, N. (2021). Individual and Environmental Explanations for Violent Extremist Intentions: A German Nationally Representative Survey Study. Justice Quarterly, 1–22. doi:10.1080/07418825.2020.1869807

Saari, A. (2021, December 10). Education governance is haunted by the ghosts of future past. “Future of Education – to whom and for what?”. FuturEducation, Helsinki, Finland.Sadan, N., & Alkaher, I. (2020). Development and formation of ESE policy: learning from teachers and local authorities. Environmental Education Research, 1-25.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Sage.

Seller, S. (2021). “Synthetic governance: The emergence of new cognitive infrastructures in education policy” Oct. 7, 2021

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books.

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2021). What is in a Reference? Theoretically Understanding the Uses of Evidence in Education Policy. In Karseth, B., Sivesind, K. and Steiner-Khamsi (Eds.) Evidence and Expertise in Nordic Education Policies: A Comparative Network Analysis from the Nordic Region. Palgrave.

Tarlau, R. (2015). How Do New Critical Pedagogies Develop? Educational Innovation, Social Change, and Landless Workers in Brazil. Teachers College Record, 117(110304).

Torres, C. (2002). The State, Privatisation, and Educational Policy: A Critique of Neo-Liberalism in Latin America and Some Ethical and Political Implications. Comparative Education, 38(4), 365-385.

Youdell, D., Lindley, M., Shapiro, K., Sun, Y, & Leung, Y. (2020). From science wars to transdisciplinarity: the inescapability of the neuroscience, biology and sociology of learning. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(6), 881-899.