Some physics instruments can be quite captivating due to, for instance, their peculiar shape or material. Take this pear-shaped object known as Nicholson’s hydrometer, for example. With the anniversary of the Great Fire of Turku of 1827 taking place on 4 September, we decided to select as the object of the month one of the treasures that survived the blaze and now features in our collection. What is this pear-shaped, streamlined, metallic object known variously as an areometer, a gravimeter, a densimeter and a hydrometer? The names tell us very little about the object itself, so let’s find out more.

A distinctive hydrometer

A guide to the Helsinki University Museum from 1982 explains that the Royal Academy of Turku had established its Cabinet of Physics as early as the 18th century by collecting various instruments used for observation and teaching. A particularly significant contribution was made by Gustaf Hällström, professor of physics, who acquired a number of devices for the Academy in the early 19th century. Now, that name rings a bell! There is a street named after him at Kumpula Campus. And come to think of it, it was thanks to Hällström’s laudable lobbying efforts that the Royal Academy of Turku built an observatory, designed by Carl Ludvig Engel, in 1819.

But back to the hydrometer: what was it used to measure again? Hydrometers are instruments used to measure the specific gravity (or relative density) of a liquid in relation to water. Nicholson’s hydrometers differ from similar instruments in that they are completely immersed in water when used.

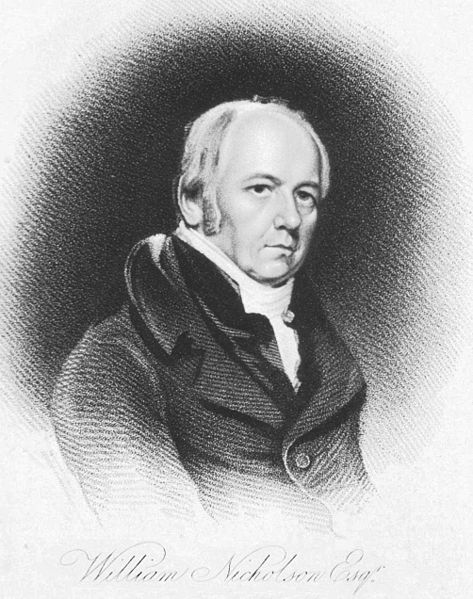

But who was William Nicholson?

And why is his surname associated with the name of our object? William Nicholson (1753–1815) was a chemist, translator, publisher, scientist, inventor and civil engineer, who in 1797 established the Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, generally known as Nicholson’s Journal. And most importantly, he developed the hydrometer.

Bought in London

The hydrometer included in the University Museum’s collection was bought in 1814 from John Newman in London. At the time, a new, impressive Academy building was being completed in Turku next to the local cathedral, and new acquisitions were being made for the Cabinet of Physics. The Academy also made other purchases, such as a new robe for the rector, bronze bust of Alexander I of Russia as well as a pedestal and silver case for the Academy charter (1817). John Frederick Newman (1783–1860) was a maker of mathematical, optical and nautical instruments, whose meteorological devices were acquired by observation stations throughout the British Empire. He was also instrument maker by appointment to the Royal Institution, in Albemarle Street, London.

When searching for images of Nicholson’s hydrometer online, you quickly discover that they were mostly of a cylindrical shape. Such hydrometers are included in the collections of several universities, but the pear-shaped hydrometer at the Helsinki University Museum appears to be a more uncommon type. Professor Gustaf Hällström determined the temperature corresponding to the maximum density of water more precisely than anyone before him. The hydrometer was probably also connected to his research.

The Great Fire of Turku devastated the Cabinet of Physics

More objects were added to the Cabinet of Physics after the Academy moved to Helsinki and was renamed the Imperial Alexander University. The objects were displayed not only in the Main Building, designed by Carl Ludvig Engel, but also in a separate department building for physics, completed in 1911 at Siltavuorenpenger. The collection remained open to the public for a few hours a week until the mid-1900s. Today, objects from the Cabinet of Physics are on display in the Helsinki University Museum’s permanent exhibition.

Unfortunately, most of the devices used in the Academy’s physics teaching were destroyed in the Great Fire of Turku in 1827. But why did some survive? Were they kept in a different location? The answer can be found in the article Physics by Peter Holmberg, late professor of physics, in a guide to the Arppeanum building published in 2003. In his article, Holmberg cites the University’s list of acquisitions from 1827, which states that all of the instruments in the Cabinet of Physics were completely destroyed, with the exception of those pieces of equipment that were out on loan at the time of the fire. Similarly, some of the University Library’s books survived because they had been lent out to professors, who had taken them to their country residences. Only four items from the Cabinet of Physics were rescued: the hydrometer, a Gregorian telescope, the Magdeburg hemispheres and an electric cannon. All these objects are currently on display in the Helsinki University Museum’s permanent exhibition, The Power of Thought, in the University’s Main Building.

Pia Vuorikoski, Head of Exhibitions

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services.

Sources:

Peter Holmberg: Physics. Helsinki University Museum – Research, Art, History. Helsinki 2003.

Renja Suominen-Kokkonen (ed.): Helsingin yliopiston museo. Helsinki 1982.

http://physics.kenyon.edu/EarlyApparatus/Fluids/Nicholsons_Hydrometer/Nicholsons_Hydrometer.htmlRenja Suominen-Kokkonen (ed.): Helsingin yliopiston museo. Helsinki 1982.

Pia – It is so good to hear that this important scientific instrument has survived. It may also be of interest to readers that Nicholson, along with his colleague Anthony Carlisle, was the first to split water using a voltaic battery in 1800 – this process is now called electrolysis and plays an important role in the development of clean energy.

If you are interested in finding out more about William Nicholson and his other inventions take a trip to http://www.nicholsonsjournal.com