The collections of the Helsinki University Museum include eight gas masks, of which seven are from the 1930s and intended for the civilian population. The University Museum has received the masks from hospitals and University of Helsinki departments. The collections also include an equine gas mask dating back to the 1930s or 1940s which is of an unknown origin.

In 2015 we made plans to place one of the civilian gas masks on display in the University Museum’s new main exhibition, The Power of Thought. However, we had to scrap these plans at the last minute when we discovered that the filters of old gas masks may contain asbestos.

In spring 2020 we decided to find out whether these suspicions were true. In this blog post, we explain how we investigated the matter and what we eventually found out.

Asbestos in filter cartridges

The connection between the filter cartridges of old gas masks and asbestos has long been known around the world. However, the focus has been on the workers of factories producing gas masks during the Second World War whose health and causes of death were analysed in the 1970s and 1980s in Britain and Canada, for instance. Those exposed to asbestos at work have suffered from, for example, lung cancer, to a far greater degree than other members of the population.

No research-based information is evidently available on the asbestos exposure of contemporary gas mask wearers or current gas mask owners and wearers. Possible risks were not properly addressed until the 2000s.

In 2014 the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) investigated 34 old British and German gas masks. The results showed that the filters of 29 gas masks contained asbestos, and six filters included blue asbestos, considered the most hazardous for health. The HSE decided that old untested gas masks should not be handled or worn as teaching aids in schools because visually distinguishing between hazardous and safe filters is difficult or impossible.

In Finland, the issue of asbestos in gas masks first arose in public in 2017 when the Varusteleka Oy company, among others, had to stop selling filter cartridges for the Soviet GP-5 and PDF-2 gas masks and ask customers to return any cartridges they had bought. The recall was initiated by the Finnish Safety and Chemicals Agency, which had had 12 filters from the 1980s tested by the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. Asbestos had been found in the particulate filter layers of all filters.

The presence of asbestos is characteristic of the filter layers of old gas masks made not only in Britain, Germany and the Soviet Union, but also in other countries. The phenomenon affects museums, schools, collectors and hobbyists alike. Asbestos can also have been used in filters manufactured in Finland. For example, Väestönsuojeluopas, a guide published by the Finnish civil defence organisation Suomen Väestönsuojelujärjestö in 1962, features a structural drawing of a gas mask filter. The dust filter is said to be made of cellulose and asbestos fibre.

Old gas masks are common in museum collections, but they are particularly popular among collectors. Many of the collectors acquire gas masks for their own use, to wear.

Authorities throughout the world have warned that, as a gas mask filter ages, it can become brittle, in which case asbestos fibres will be released into the air for the wearer to breathe in, and possibly onto the surfaces of the gas mask and the bag it is kept in. The asbestos issue has also received increasing attention from international hobbyists. It is generally recommended in online forums and chatrooms for hobbyists that old filters be replaced with new, safer ones. However, a significant number of the owners and wearers of historical gas masks are unaware of the risks.

Due to the lack of research-based information, it is difficult to say with certainty how easily asbestos fibres are released into the air outside the filter and whether asbestos fibres released from a particulate filter layer can pass through an active charcoal filter and enter the wearer’s respiratory tract. Similarly, we do not know how likely this is and how significant a health risk asbestos poses to hobbyists, collectors and museum staff.

Development of gas masks

Chemical warfare was invented before the Common Era, but the more extensive use of chemical weapons dates back to the First World War. The poison gases used included various chemical substances, such as the corrosive mustard gas, which caused severe skin and lung damage. Serious cases of mustard gas poisoning led to the victim’s death in just a few days or weeks.

The new weapons required new types of protection. The predecessor of the modern gas mask had been patented in the United States as early as the mid-1800s, and it was capable of filtering particulates from the air. After 5,000 French soldiers died in April 1915 of the chlorine gas released by the Germans during the Battle of Ypres in Belgium, several countries made frantic efforts to develop gas masks and filters. For example, a gas mask based on an activated charcoal filter was developed in Russia that same year.

The First World War eventually came to an end, but concerns about chemical warfare have not abated. Despite the use of gas weapons having been prohibited by the 1899 Hague Declaration Concerning Asphyxiating Gases and the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare, both parties to the war had used poison gases extensively, killing a total of 90,000 people. It appeared evident that the use of these weapons would continue in future wars and conflicts.

Finland began to prepare for the use of poison gases in the 1920s. Suomen Kaasupuolustusyhdistys, an association for defence against gas weapons, was established in 1927, and as of 1930, this association functioned as an organisation known as Suomen Kaasupuolustusjärjestö. The duties of the organisation included public education and training, and it also held gas defence demonstrations, published the popular Kaasutorjunta magazine and sold Finnish civilian gas masks.

Gas masks equipped with various filters and features were manufactured for various uses. Servicemen required more efficient protection than civilians. Finnish newspapers published instructions for making gas masks at home, and in the most acute emergencies, people could also protect themselves against chemicals with, for example, moss, a wet cloth or a tissue filled with soil, sawdust or crushed charcoal.

Gas masks for the civilian population in the Helsinki University Museum’s collections

The collections of the Helsinki University Museum include two types of gas masks for the civilian population: Finnish civilian gas masks from the early 1930s and civil defence gas masks from the late 1930s.

The manufacture of Finnish civilian gas masks began in 1930. Thousands of such masks were sold to members of the public, and the Belgian government also ordered a large batch. The user manual for the masks from 1931 explains that the filter contains “50 parts by weight of activated mask charcoal and 50 parts by weight of special soda lime” and that the filter does not protect from dusty forms of poison gases. However, separate ‘dust filters’ were available for the civilian gas mask. Because asbestos has been found to be associated with particulate filters, a filter used only for gas protection should not contain asbestos. However, asbestos may be present in a ‘dust filter’, but no such item is included in the University Museum’s collections.

In late 1938, the Suomen Kaasupuolustusjärjestö organisation developed a new civil defence mask for civilian use, with small adjustments made to the mask early next year. The civil defence gas masks that entered the market in early 1939 included the filter for the civil defence force gas mask M/38, but subsequent masks included the filter for civil defence gas mask M/39 with separate gas and dust filter layers and a filter with lower profile. The existence of the dust filter layer indicates the possible presence of asbestos. Gas mask collector Liam Robinson also believes that the filter cartridge of the Finnish civil defence mask M/39 contains asbestos.

Results of the asbestos analyses of the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health

Because the issue of asbestos in gas masks had troubled the staff of the Helsinki University Museum for years, we decided to contact the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health in spring 2020 to enquire about the possible analysis of these objects. Specialist Annika Lindström became intrigued because she had investigated the Varusteleka filters in 2017, and the question of asbestos fibres passing through the filter had lingered in her mind.

We initially chose four gas masks for analysis: two Finnish civilian gas masks from the early 1930s and two Finnish-made civil defence gas masks from ca 1939. Our hypothesis was that the former would not contain asbestos, while the latter would. Later, we also decided to send the equine gas mask for analysis.

The selected gas masks were delivered to the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. The purpose was to find out whether the filter cartridges contain any asbestos, and if they do, whether it can be released and end up on gas mask surfaces and cases. Annika Lindström was also interested in studying whether there is any asbestos in the air breathed in by the mask wearer.

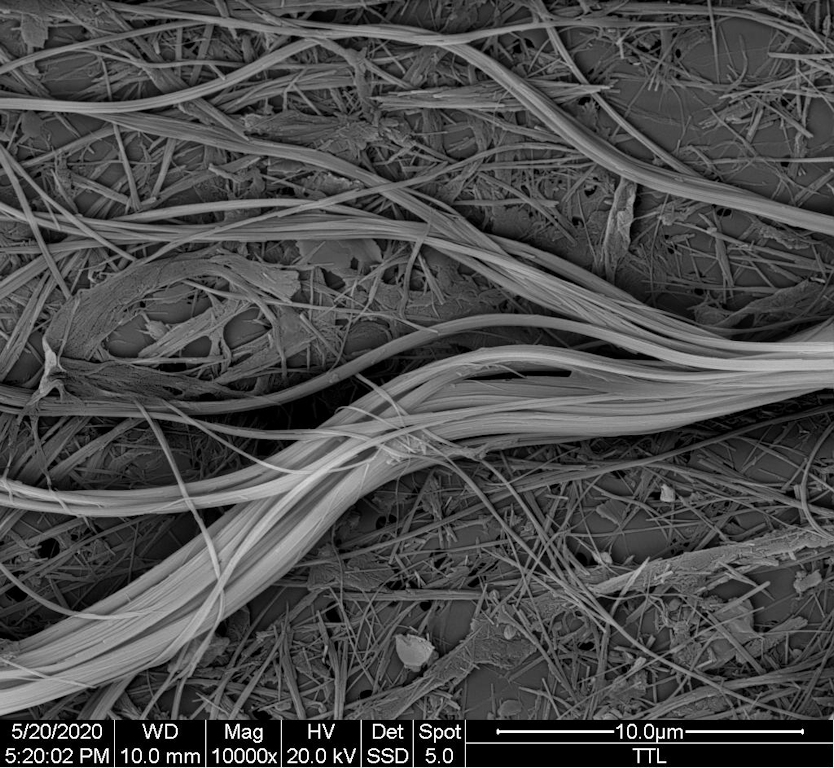

As expected, the Finnish civilian gas masks from the early 1930s did not contain asbestos. However, asbestos was found in the filter cartridges of both of the civil defence gas masks of 1939, although they are of different types. It was found, above all, in the cotton-type material on the outer side of the filter. The analyses were performed using material samples.

Because the filters of both civil defence gas masks were found to contain asbestos, dust samples previously taken from the surface of the objects as well as from their mask cases were analysed next. These analyses confirmed that both filters had released asbestos fibres. In addition, the protective cardboard partly attached to one of the filters had not prevented the spread of fibres outside. An air sample was also collected from one of the filter cartridges to find out whether asbestos fibres can pass through the active charcoal filter into the mask wearer’s lungs. The asbestos found in the air sample demonstrates that this can, indeed, occur.

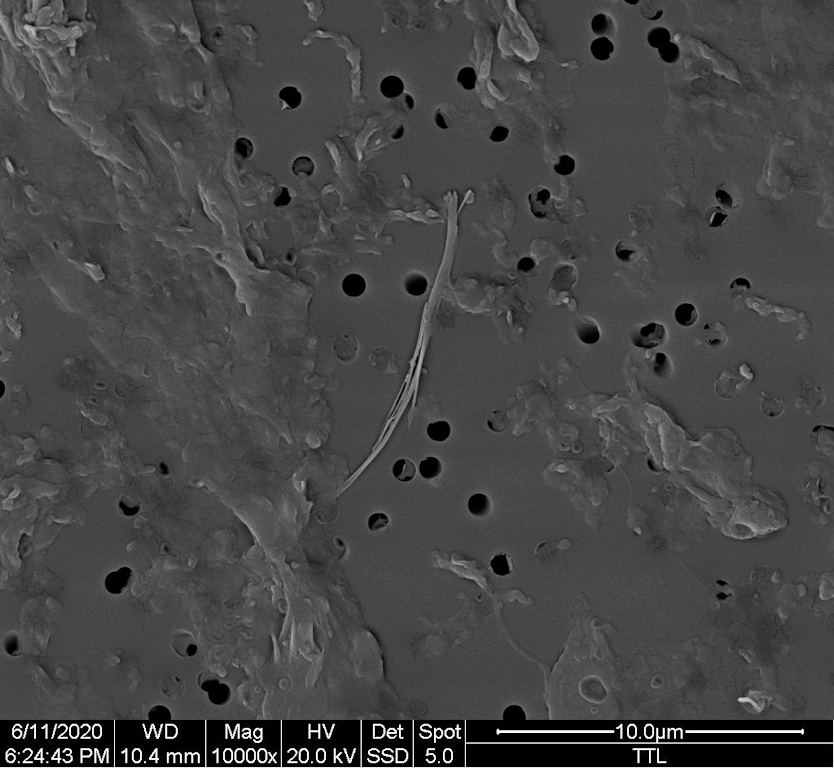

Due to the interesting results obtained from the analyses of human gas masks, the decision was made to investigate the equine gas mask included in the University Museum’s collections. Its filter cartridge differs structurally from that of the civil defence gas masks in that it is more tightly sealed, but the plate at the bottom has an air intake opening with a rubber cap. A grey felt-like fabric can be seen through the rubber cap under the metal netting.

A dust sample taken with a cotton bud through an air intake opening contained a great deal of asbestos fibres, unlike a sample taken from the mask case. It is possible that a more tightly sealed filter does not release asbestos in the environment as easily as models with mesh filter plates, but meaningful conclusions cannot be drawn based on a single filter.

Concluding remarks

Although the number of gas masks studied for this blog post is very small, it seems evident that the filter cartridges of old Finnish-made gas masks often contain asbestos.

Gas mask collectors participating in online chatroom conversations have stated that wearing an old gas mask poses a health risk, but claimed that other handling of old gas masks is safe. The analyses conducted by the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health indicate that this view is too optimistic because asbestos fibres can be released from cartridges both when breathing through the filter and during storage and handling. However, it is not very likely that the handling of a gas mask would lead to the release of asbestos fibres in such abundance that the Finnish limit value for asbestos, 0.01 fibres per cubic centimetre in the breathing air, would be exceeded. In contrast, it is possible that asbestos fibres land on room surfaces, which requires action under the decree on health-related conditions of housing. When breathing through a gas mask, the limit value is clearly exceeded.

Because filter cartridges have not been extensively studied, it is difficult to say whether asbestos is only released from certain filter models or whether all asbestos-containing filters are hazardous to health. As long as no detailed information is available, the handling and, above all, wearing of all old gas masks should be avoided. The masks should be stored in a tightly sealed and undamaged plastic bag, for example, in a re-sealable freezer bag.

If a gas mask is to be put on display in a museum exhibition, it must be ensured that the visitors and staff are not exposed to asbestos. At the British Royal Armouries Museum, for example, an asbestos specialist has been commissioned to apply acrylic sealer over the openings of a filter cartridge, thus preventing the release of fibres outside the cartridge.

Henna Sinisalo, curator

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services.

The author would like to thank Annika Lindström and Heli Lallukka of the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health for the performance and interpretation of analyses as well as productive cooperation.

Sources

Broughton, Richard 2014: Asbestos-containing vintage gas masks and helmets. Health and Safety Executive, Bootle. Link.

Dalewicz-Kitto, Suzanne & Marston, Holly 2016: Asbestos in the collection of the Royal Armouries and the conservation of a First World War German gasmask, Arms & Armour, 13: 2, 177–189. Link.

Jones, J. et al. 1980: The consequences of exposure to asbestos dust in a wartime gas-mask factory. IARC scientific publications, 30 (1980): 637–653. Link.

Kotiranta, Verna 2019: Pelottelua, tutkimustyötä ja valistusta: näin Suomi varautui kaasusotaan. Lastuja Suomen historiasta. Blog post by the discipline of Finnish history at the University of Turku, 25 September 2019. Link. (Accessed on 9 April 2020.)

Lallukka, Heli & Lindström, Annika 2017: Analysis results. Asbestos in a material sample. Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, 13 July 2017. Link.

McDonald, Alison D. & McDonald, J. Corbett 1978: Mesothelioma after crocidolite exposure during gas mask manufacture. Environmental Research, 1978; 17(3): 340–346.

Ohjeet suomalaisen siviilikaasunaamarin käytöstä, säilytyksestä ja hoidosta. Suomen Kaasusuojelujärjestö, 1931.

Onnela, Tapio 2018: Kaasusodankäynnin historiaa. Agricolan Tietosanomat. Link.

Palmén, John 1931: Kaasusodan aseet, taktiikka ja suojakeinot. Finnish Red Cross, 1931 (10): 188–190.

Rauhanen, Henna 2014: Omakohtaista väestönsuojelua, sanoi akka, kun sateenvarjonsa avasi: Kaasusodankäynnin pelosta alkanut väestönsuojelun kehitys Suomessa 1920–1930-luvuilla. Master’s thesis in history, Tampere University. Link.

Robinson, Liam 2018: Testing the Finnish M39 Civilian Gas Mask. Weaponsandstuff93. Youtube.com, 10 March 2018. Link.

Simkin, John 2019: Gas Masks in the Second World War killed more people than they saved. Spartacus Blog, 9 May 2019. Link. (Accessed on 9 April 2020.)

Decree of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health on Health-related Conditions of Housing and Other Residential Buildings and Qualification Requirements for Third-party Experts (Decree No 545/2015). Link.

TAKAISINVETO! CCCP GP-5 ja PDF-2 kaasunaamareiden suodatinpatruunat sisältävät asbestia! Varusteleka.fi, 12 September 2017. Link. (Accessed on 9 April 2020.)

Väestönsuojeluopas. Suomen Väestönsuojelujärjestö, 1962.

Väestönsuojeluvälineistöä. Kaasutorjunta: Suomen kaasusuojelujärjestön julkaisu, 1939 no 1: 16–18.

Väestönsuojeluvälineistöä. Kaasutorjunta: Suomen Kaasusuojelujärjestön julkaisu, 1939 no 2: 8.