Writer: Olli Saukko

I worked as a project researcher in the HUMANA project on its first year, 2019. My main task, with which I spent most of my time within the project, was to examine the background of the Finnish people that lived on Sugar Island in Michigan in the time period of this research, in other words, around the 1920s to 1940s. The main questions were: Where did the Finns come from, and when did they arrive on Sugar Island? What kind of background did they have in Finland or elsewhere before immigrating to America?

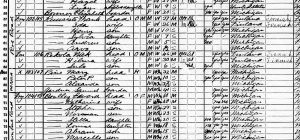

Census records as the starting point

To outline the material into a sensible amount, I decided to look for this information regarding those Finns who could be found in the federal census record of Sugar Island made in January 1920, in other words, quite by chance, just 100 years ago. In this census record, there are 25 Finnish families. Majority of these families include a husband, a wife and one or more children, a couple of them are single, and some families have Finnish boarders. So, I looked for the background of 25 heads of family, many of their partners and children and six boarders of which some had families of their own later on at the island.

The census records offered a selection of information on the Finnish people of Sugar Island. Concerning this task of mine, the useful information in these records included their ages (and along with that, the estimated years of birth), years of immigration, naturalization status, and of course current family relations. The records also included information about birthplace, but in most cases, it was not very helpful, as it only stated “Finland”, and no detailed information.

One useful detail, however, was that the records showed also the birthplaces of the children of the families, and these gave useful information about the recent background of the parents. As an example, the four sons of August and Katie Saari were born in Minnesota between 1909-1918, which tells that the family lived in Minnesota at least until 1918, and at least Katie and the children moved from there to Sugar Island between 1918 and January 1920. Some of the information was also surprising. Emma Lindburg had a son Carl in 1916. Emma was born in Finland and she and Carl both are stated to have Finnish parents, but Carl was born in Australia, which suggests that at least Emma and possibly her husband (also named Carl, how convenient!) lived in Australia just few years earlier. In the census record, Emma Lindburg’s immigration year is stated to be 1910, which would suggest, if the year is correct, that the family was in America in the early 1910s, lived or visited in Australia around 1916, and moved to Sugar Island before 1920. Seems like an unusual route to take as a young family in the 1910s, but of course it’s possible.

One useful detail, however, was that the records showed also the birthplaces of the children of the families, and these gave useful information about the recent background of the parents. As an example, the four sons of August and Katie Saari were born in Minnesota between 1909-1918, which tells that the family lived in Minnesota at least until 1918, and at least Katie and the children moved from there to Sugar Island between 1918 and January 1920. Some of the information was also surprising. Emma Lindburg had a son Carl in 1916. Emma was born in Finland and she and Carl both are stated to have Finnish parents, but Carl was born in Australia, which suggests that at least Emma and possibly her husband (also named Carl, how convenient!) lived in Australia just few years earlier. In the census record, Emma Lindburg’s immigration year is stated to be 1910, which would suggest, if the year is correct, that the family was in America in the early 1910s, lived or visited in Australia around 1916, and moved to Sugar Island before 1920. Seems like an unusual route to take as a young family in the 1910s, but of course it’s possible.

What kind of sources were available?

To find answers to the questions stated in the beginning, I used several sources. First, I looked for these Finns in the Emigrant Register provided by the Institute of Migration (Siirtolaisuusinstituutti in Turku) to find out if there were documents about their travels to America in which their place of birth could be found. This source already provided reliable information about a couple of these Finns.

Secondly, I used the records found in the collections of Ancestry, a company that provides historical records and family trees. In the Ancestry database I could search Sugar Island Finns, mainly with just their names and probable birthdates found in the census records, which were from Ancestry as well. Ancestry’s collections include immigration and travel records, military records (such as, in this case, draft cards for World War I); birth, marriage and death records and of course census records from other years than the 1920 from which I started. Through these, I could find information about the travels, marriages, death dates and the places they lived. As an addition, some of these documents included such information as the names of the parents of these people, other family relations, or their birthplace in Finland. When I went through all this material, I explained to a friend of mine that it felt that I was sort of doing family-history research – i.e. genealogy – of people who were not my relatives.

Thirdly, to fleshen up the official documents found in the collections of Ancestry and Institute of Migration, I was able to use original material from Sugar Island. One of our American members of the team, post-doc researcher Justin Gage went to do archival work at the Sugar Island in the summer 2019 and brought us hundreds and hundreds of pictures of original archive material to do with the history of Sugar Island. More information about the trip can be found in the previous blog post. The part of this collection that I used was the material that Allan Swanson had gathered and received for his study “Sokeri Saari: The Finnish Community on Sugar Island” published by The Sugar Island Historical Society in 2005. This data included written memories and questionnaires about the background of the Sugar Island Finns of the 1920s to 1940s that were filled by their descendants in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Practical challenges with the church records and other data

When looking at the source material about the Finnish people of Sugar Island, I encountered several frequent challenges. The first one had to do with the names. It was a commonplace for these kinds of Finnish immigrants to change their names into more “English” versions, so that Frans Mikko Kuusisto became Frank Mike Kuusisto or Matti Lepsu became Matt Leppi. This creates obvious difficulties, when you try to find the same people from different kinds of documents from different years with slightly different names. Furthermore, the basic documents I leaned on, the census records of Sugar Island, mainly from 1920, 1930 and 1940, sometimes had the names misspelled, and occasionally the birth years varied as well, so that the data from the censuses was definitely not fully reliable. Taking all this into account, it is quite an achievement that I was finally able to find reliable information about the majority of the Finns that resided in Sugar Island in 1920.

Of course, one could consider the information of some documents more reliable than others, for example it would make sense that the birthdates and places in the World War I draft records are more reliable than some others, as it would seem quite risky to give false information in these drafts. So it was also possible to find seemingly reliable sources. Concerning the name differences, in most cases, the changes of names were also rather obvious, such as Kalle or Kaarle would become Charles; Nikolai would be Nick and Anna would be Annie. However, all these mentioned issues created a mist of uncertainty around this task of gathering data, which is, however, understandable when looking at people on a small island on a different continent 100 years earlier.

Another challenge had to do with the availability of the Finnish church records (available in Finnish) from the years when the Sugar Islanders were born. The idea was that when we found the birthdates and birthplaces of the Sugar Island Finns, we could look for the information about them in the Finnish church records from those towns and cities from those years, and this would work as the basis of further gathering of data about their Finnish roots. Unfortunately, this turned out to be quite tricky. There are some church records openly available in the collections of the National Archive of Finland, but because of the privacy regulations, the use of material from late 19th century and very early 20th century is mostly restricted. It is possible to research them, however, as the staff of National Archive informed us, but it must be done by separately applying for a permission to use each of these records.

I had a look on the several church records of those birthplaces of Sugar Island Finns that I found out, and checked which of them would be available. I found out that most of them are indeed not open from the years we need, but end just around 1860s or 1880s, just before most of the people we are researching have born. Fortunately, I did find one example. He was Frank Mike (Frans Mikko) Kuusisto in the church records of Honkilahti from the 1880s, which were, surprisingly, openly available online. Finding him, along with his parents and siblings, raises hopes that it will be possible to track the background of other Sugar Island Finns later as well, even if the process can – and probably will – be demanding.

Keywords: Sugar Island, Finnish American history, Finnish church records

My late wife, Nancy was 100% Finn and whose maternal and paternal settled on Sugar Island. Those surnames were Keko and Kauppi. I suggest that you read SUGAR ISLAND SAMPLER and KARAILA. Both availabe on Amazon.

Feel to contact me if you have an y questions.

Bill Saunders grapeaccn @sbcglobal.net, phone 269/375-0044.

Dear Mr. Saunders,

First of all I am sorry to hear that you wife passed away. We do remember her and you from our visit in 2015. We have done a tremndous amount of research ever since and of course have read Arbic etc. we have the original Swanson notes and an unpublished biography by Frank Aaltonen, to name a few cool things. If you look at some of our interactive maps, you will find the Kauppi homestead there as well. We will donate all of our materials to Sugar Island Historical Preservation society when we are done.

All the best to you,

Rani Andersson