The authors of this blog post first presented the Hungarian Easy Language map in 2021 (Horváth & Ladányi 2021a). About two years have now passed since the manuscript was completed. In the last chapter of the paper, we discussed the future. We stated that we considered it essential to have a set of rules adaptable to the specific features of the Hungarian language. We wrote about training courses for people with intellectual disabilities. We wrote about planning conferences. And we also wrote about the need for literary works to be remodelled in a simple, easily understandable way. We would now like to report on these developments.

About the rule systems available in Hungarian

In Hungary, we mainly use the Inclusion Europe code of practice, published in 2009 (Inclusion Europe & ÉFOÉSZ 2009). We consider it important that additional codes of practice are made available. Therefore, we have translated the guidelines of the International Federation of Library Associations and Organisations, published in 2010 (Nomura, Nielsen, & Tronbacke 2010), into Hungarian. The collection of texts to which these guidelines belong is the first to contain Hungarian translations of scientific research reports published in English in Hungary (Horváth & Ladányi 2021b).

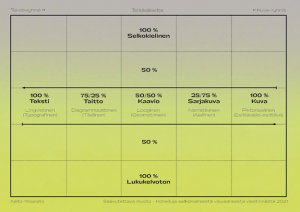

With the permission of the Finnish Easy Language non-profit organisation ‘Selkokeskus’, we have also translated the Easy Finnish Indicator 2.0 guide into Hungarian. It is currently undergoing linguistic and professional proofreading, but will soon be available to professionals and interested parties in the field.

In cooperation with the Petőfi Literary Museum in Budapest, we have developed guidelines for the simple/easy-to-understand reinterpretation of literary works and the simple/easy-to-understand illustrations of such works, based on Finnish and German models (Hennig & Jacob 2022; Uotila 2019) (Horváth, Nemes-Jakab & Pechan 2022).

Training programmes

In 2022, the Association for People with Intellectual Disabilities of Csongrád County, Szeged, accredited the ‘Easy to Understand? Accessible through training!’ course. The 22-hour training course was completed by eight students the same year. Since then, certified persons with intellectual disabilities have been involved in checking the comprehensibility of texts and illustrations received from various clients, as paid work (e.g. Petőfi Literary Museum in Budapest: János Vitéz simply / easily understandable or the texts of permanent exhibitions of the Kassák Museum in Budapest and the Ethnographic Museum in Budapest, which will open on 1 September 2023).

Conferences

In 2021 and 2022, the Eötvös Loránd University Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education held an online professional conference, where Easy Language was a priority in terms of accessibility. The special feature of the professional event was that it was the first in Hungary to address the topic of Easy Language as an independent theme. In addition to sharing practical experiences, its focus was on current knowledge of professional theory.

Rewriting literary works

We have already referred several times to our cooperation with the Petőfi Literary Museum in Budapest. Sándor Petőfi is a famous Hungarian poet. The 200th anniversary of his birth was celebrated on 1 January 2023. To mark the occasion, a simple, easy-to-understand ‘translation’ was produced of one of his most famous narrative poems in verse, János the Valiant. This poem is compulsory reading in grades five to six of the Hungarian school system. A contemporary Hungarian writer, Gergely Nógrádi, rewrote the descriptive parts of the poem in prose form and the dialogues in verse. The text is accompanied by a very carefully designed, easy-to-understand illustration by Panni Bodonyi, to support the interpretation of the text by pupils with intellectual disabilities. The illustration has received great praised. Ilona Sallai and Zsolt Cziráki checked the comprehensibility of the text and the illustration (Petőfi, Nógrádi & Bodonyi 2022).

All these activities were preceded by careful exploratory work and research (Nemes-Jakab 2022). We collected the literature available in German, English, Italian and Finnish on the reinterpretation of literary works. Given that no simple/easy-to-understand literary work had been produced in Hungary, we considered it important to explore the experiences of practitioners who had faced similar challenges. Thus, in ten focus groups, we interviewed various Hungarian professionals (e.g. literary translators, actors and theatre dramaturges, and illustrators of children’s and youth books). On the basis of the results of this literature review and the focus group interviews, we developed two new sets of rules (how to write easy-to-understand literature, and how to make easy-to-understand pictures to literature text). The research programme will continue in 2023 with the study of the practical applicability of the finished publication in a school setting.

We look forward to reporting back on further developments in another two years.

In the meantime, we would like to let the Honourable Reader know that we are open to all suggestions and to participation in international collaboration. Feel free to contact us.

Péter László Horváth, Associate Professor, Apor Vilmos Catholic College, Vác komplexmentor (at) gmail.com

Lili Ladányi, assistant Professor, University of Szeged Juhász Gyula Faculty of Education, Szeged ladanyi.lili (at) szte.hu

References:

Hennig, M. & Jacob, J. 2022. Literatur in vereinfachter Sprache: Einfachheit und literarische Ästhetik. [Literature in simplified language: simplicity and literary aesthetics.] Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik, 52: 89–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41244-022-00250-6

Horváth, P.L. & Ladányi, L. 2021a. Easy Language in Hungary. In Lindholm, C & Vanhatalo, U. Ed. Handbook of Easy Language in Europe. Berlin: Frank&Timme. 219-252. ISBN 9783732907717

Horváth, P.L. & Ladányi, L. 2021b. Válogatás a könnyen érthető nyelv nemzetközi szakirodalmából. [A selection of international literature on easy language.] Szeged: Juhász Gyula Felsőoktatási Kiadó. ISBN 9766155946516

Horváth P.L., Nemes-Jakab É. & Pechan E. 2022. Szépirodalom – könnyen érthetően? [Fiction – easy to understand?] Fogyatékosság és Társadalom 2022.1:88-100. http://doi.org/10.31287/FT.hu.2022.1.8

Inclusion Europe & Értelmi Fogyatékossággal Élők és Segítőik Országos Szövetsége 2009. Információt mindenkinek! A könnyen érthető kommunikáció európai alapelvei. [Information for all: European standards for making information easy to read and understand.] Brüsszel – Budapest: Inclusion Europe – Értelmi Fogyatékossággal Élők és Segítőik Országos Szövetsége.

Nemes-Jakab É. 2022. Rámpa a sövényhez. Expedíció az Északi-sark könnyen érthető irodalom felfedezésére. [Ramp to the hedge. An expedition to discover to the Arctic easy-to-understand literature.] In Földes, Gy., Major, Á. & Szénási Z. (szerk.): Műfordítás és más extrém sportok. Írások Kappanyos András 60. születésnapjára. [Art translation and other extreme sports. Writings for the 60th birthday of András Kappanyos.] Budapest: Reciti Kiadó. 231-238.

Nomura, M.; Nielsen, G.S.; & Tronbacke, B.I. 2010. Guidelines for easy-to-read materials. Hága: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions.

Petőfi S., Nógrádi G. & Bodonyi P. 2022. János vitéz 1-3. ének. Egyszerűen érthetően / könnyen érthetően. [John the Soldier 1-3. canto. Plain Language / Easy Language.] Budapest: Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum.

Uotila, E. 2019. Selko Suomessa – selkokielen kehitys ja ja sovelluksia. [Selko in Finland – the development and applications of Easy Language.] Puhe ja kieli, 39.4:307–324. https://doi.org/10.23997/pk.74581