The writer of the blog: Velga Polinska

Since the birth of my son with Down syndrome, I have been trying to get a glimpse of the veiled world of people with perceptual disorders. For me personally, it is important to give my son the most opportunities I can. During these years, I have noticed that here, in Latvia, the available health care services mostly aim at bringing people with various intellectual disabilities as close as possible to the rest of society, where they are often judged by the same criteria. However, it was interesting to find out whether the rest of society can adapt their behavioral patterns to communicate with people with intellectual disabilities on the level they are able to. And once I started working on my Master’s thesis, I chose to have a closer look at the real communicative situation in Latvia.

How it looks

It is not a secret that effective communication is the basis of inclusive society, which provides education, work, and social life opportunities to every person. To start, it was important to understand whether there are any opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities of establishing effective communication in public bodies. Therefore, I created a survey which was then sent to different state and municipal bodies. There were 90 respondents: 26 social service offices, 20 health care facilities, 19 museums, 16 courts and 11 other state and municipal bodies.

The survey highlighted several tendencies regarding the work-based training in communication with people with perceptional disorders, as well as applied communication strategies and awareness of Easy Language.

Appropriate training: or rather insufficiency of it.

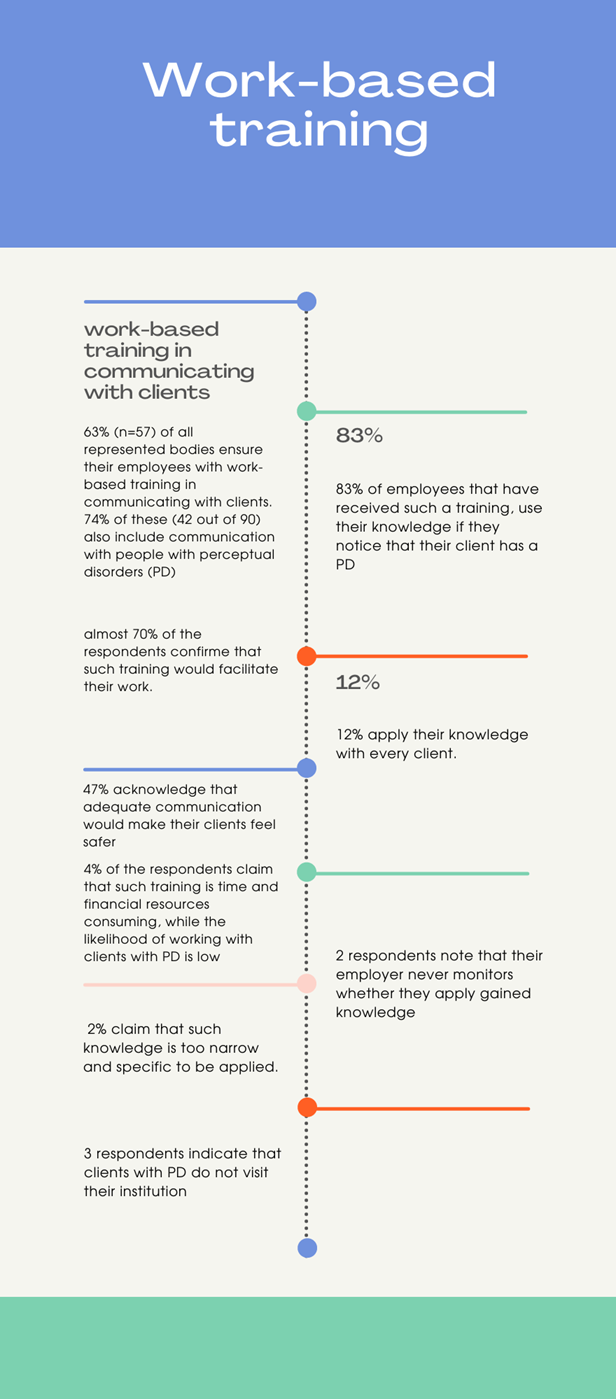

Only 63% of all represented bodies ensure their employees with a training on communication with their clients, and only 74% of these cover communication with people with PD. 83% of those who have received such a training use their knowledge whenever they see that their client has a PD, but 12% use their knowledge with all clients. 47% of all the respondents recognize that adequate communication would make their clients feel safer. However, 4% claim that such a training is very demanding, while the likelihood of working with clients with PD is very low. 2% believe such knowledge is too narrow and specific, and 3 respondents indicate that people with PD do not attend their institution.

It is clear that the work-based training would make the employees and their clients with perceptual disorders (PD) feel safer, reduce misunderstandings and allow to establish effective communication. On the other hand, it is noticeable that there are still few respondents that do not understand the necessity of such communication: they claim that the training would require too many resources; besides, they do not work with clients with PD very often. However, clients may be choosing not to visit public bodies for the reason that they have not experienced effective bidirectional communication.

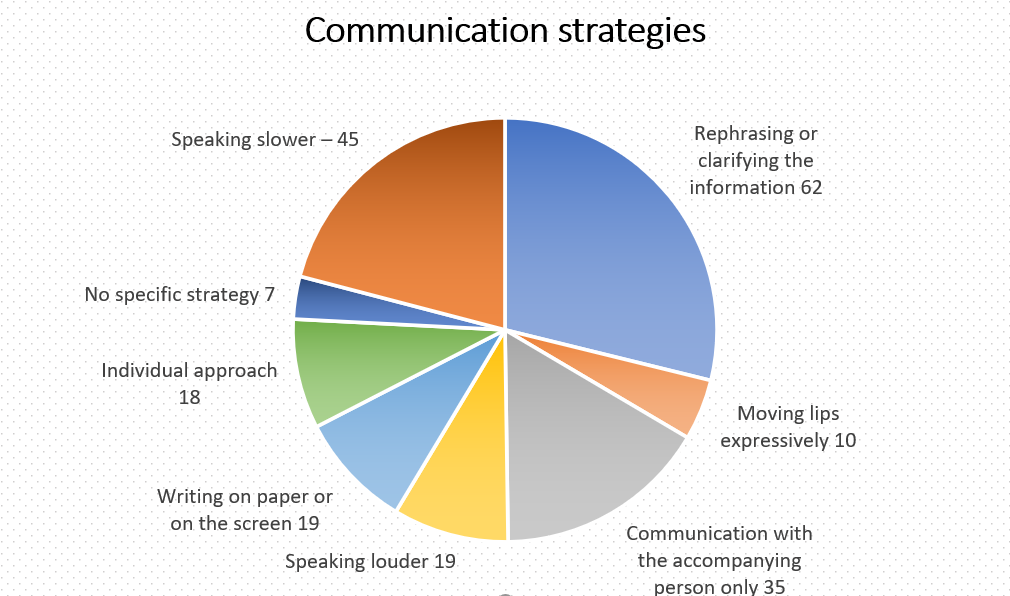

Communicative strategies can be correlated with the frequency of their use as follows:

When communicating with clients with perceptional disorders, majority of the employees (68%) choose to rephrase or clarify the information. Alarmingly that 39% of the respondents communicate with the accompanying person only. 50% speak slower, 21% speak louder and also 21% write the information on the paper or the screen. 20% of the respondents search for individual solutions, 10% think that moving their lips expressively is helpful, and 7% do not apply any specific strategy.

The given responses clearly show that only a few of the applied strategies are appropriate in communication with people with PD. Although, the most often used strategy — rephrasing or clarifying the given information — is also the most effective (especially in Easy Language), we cannot disregard that almost 40% of the respondents tend to ignore their clients, communicating with the accompanying person only. Likewise, often enough employees choose inappropriate strategies, such as writing the information on a piece of paper or moving the lips expressively.

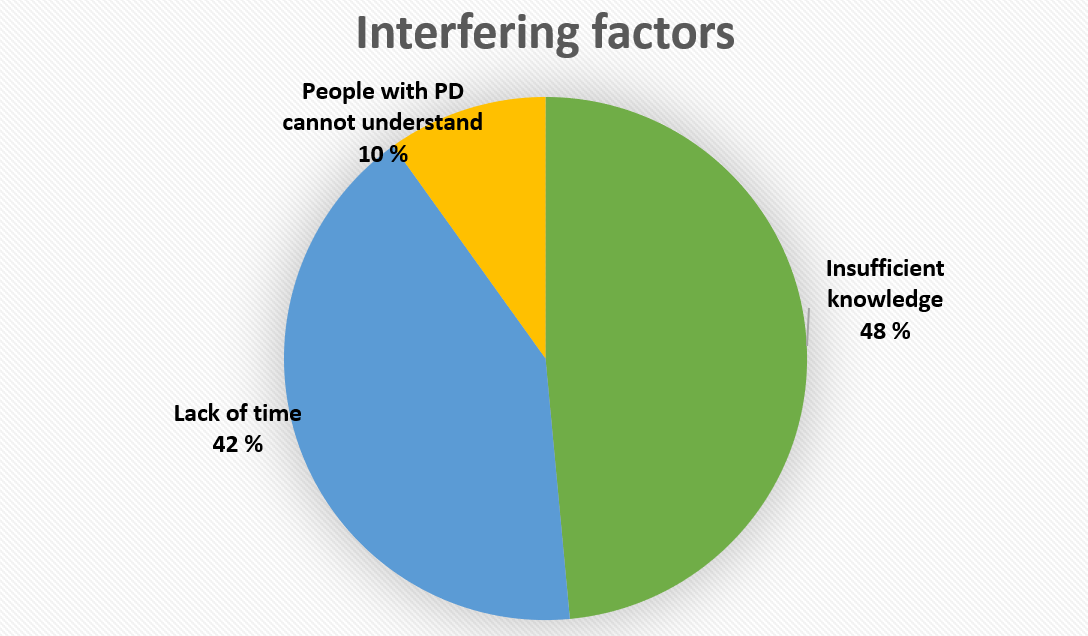

Factors that according to the respondents hinder successful communication with people PD:

48% of the respondents confirm that their knowledge is insufficient to provide effective communication with their clients with PD. 42% claim that the visits are too short , and 10% believe that people with PD most probably will not understand what they are told.

In other words, employees often do not have time to establish effective communication, and they also do not know how. Besides quite a few also believe that people with PD are not able to understand any explanations or clarifications; therefore, they choose to communicate with the accompanying person.

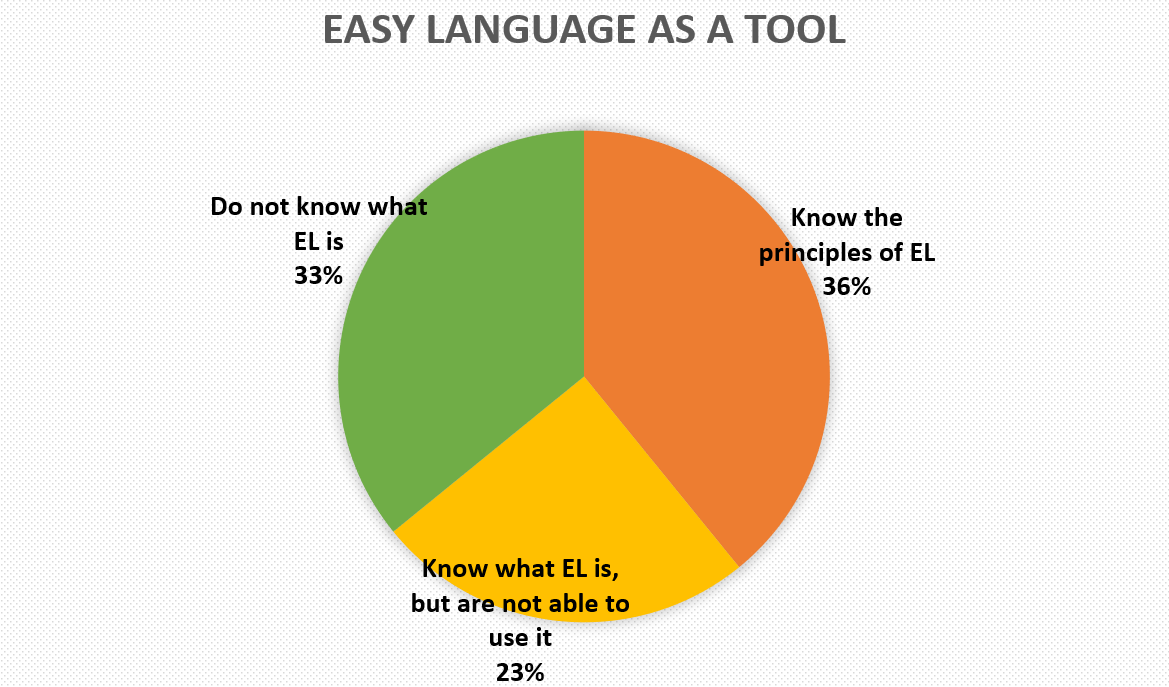

Easy Language awareness: finally, I wanted to know whether the respondents have considered using Easy Language in order to communicate effectively with their clients.

36% of the respondents claim that they know the principles of Easy Language and can apply them, 23% know what Easy Language is, but do not know its principles and thus cannot use it. 33% do not know what Easy Language is at all.

Turns out that Easy Language still is underrated as a communication tool in Latvia – 33% of the respondents do not even know what it is.

Technically, these are just numbers; however, the results of the survey showcase inclusion and equality gaps. So, the question is –

What to do?

First of all, all response groups of the survey clearly showed that public bodies’ employees are in need of an appropriate training programme on how to communicate with their clients, including clients with PD.

Another very important step towards successful communication and hence an inclusive society is the promotion of Easy Language. Knowledge of the Easy Language principles and ability to apply them would significantly enhance effective communication, thus increasing independence of the people with PD and reducing the need for assistants, accompanying persons, or care providers in daily activities such as going to the museum.

Within the project “Promoting Easy-to-Read Language for Social Inclusion”, the guidelines for Easy Latvian have been developed, which will be freely available in the coming months. The authors of the guidelines hope that these will be a good tool to significantly increase the use of written Easy Language in different institutions in Latvia.

However, I believe that not only Easy-to-read but also spoken Easy Language is of paramount importance. Thus, any of the following solutions might increase public service availability: 1) websites including not only written information but also audio materials; 2) museums’ offer of audio-guides in Easy Language; 3) Easy Language interpreters; 4) easily available theoretical and practical training in Easy Language principles to ensure effective communication; 5) destigmatization of Easy Language.

Moreover, communication and service availability can be enhanced, for example, by planning a longer visit for clients with PD or checking whether the setting of the conversation is adapted to meet the needs of the client. Not always caring for the clients require enormous resources; sometimes, it is just a matter of an attitude. Every person regardless of their position can cultivate an inclusive environment. At the same time, it should be kept in mind that inclusion is bidirectional, and appropriate communication tools would allow people with PD communicating their outlook, hence enriching our society with new and original ideas.

About the writer: Velga Polinska (Mg. Art., Mg. Phil.) is a teacher, translator, and interpreter. She is a board member of the society “Down Syndrome Latvia” and a junior representative of the Latvian Alliance for Rare Diseases. Currently she takes part in the project “Promoting Easy‑to‑Read Language for Social Inclusion” (Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia).

The article is based on my Master’s thesis:

Velga Polinska (2021) “Interpreting for People with Perceptual Disorders” (“Tulkošana cilvēkiem ar uztveres traucējumiem”). Riga: University of Latvia.

Available: https://dspace.lu.lv/dspace/handle/7/56137