The author of this blogpost is Mia Laitinen*.

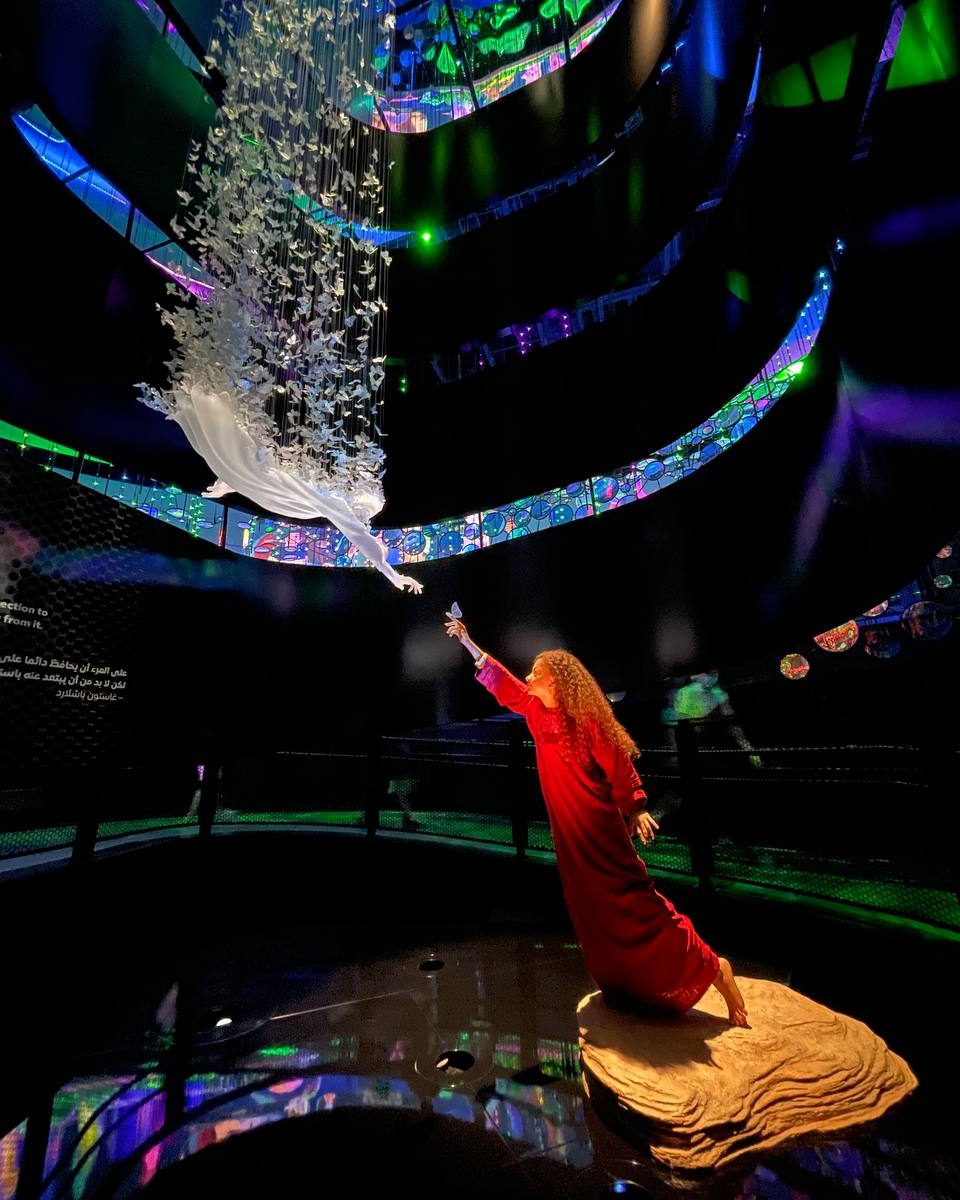

Featured image credits: Ayman A Rezeqallah, Faculty of Education, Birzeit University

*Mia is a Master’s student at the Faculty of Education, University of Helsinki. Currently she is writing her thesis. For this blogpost, Mia met online with OLIVE members from Birzeit University and discussed with them themes related to the project aims.

I was kindly introduced to three participants with undeniable impact for OLIVE project. The participants are Ahmad Aljanazrah, Assistant Vice President of Academic Affairs at Birzeit University and coordinator for the project, welcoming the discussion and ideas concerning OLIVE; Refa’ Ramahi, Dean of the Faculty of Education at Birzeit University, who’s working on planning structures of workshops and developing practicum courses; and Abdallah Bsharat, faculty member at Curriculum and Instruction department of College of Education at Birzeit. Abdallah is supporting co-operation in the school field and the upgrading of courses.

All the participants have worked with the project from its early stages to develop the quality of teacher education in Palestine with colleagues around the world. When sending the interview questions all the way from Finland I was curious to know, what kind of roles are needed to run an international project such as OLIVE. I have come to realize that it’s very important to include the administration level in the co-operation as well as the sense of believing in the project. This engagement can be seen in participating in activities and common projects and planning, but also as an aim to reach goals that flow at an abstract level. Such goals include equality in teacher education and sensitive learning environments.

From a Finnish perspective, I guess that, at some level, these apply to our educational system as well. In addition, during the interviews I came to realize these are issues we’re dealing with all around the world. When adding the current pandemic situation into the plot, this turns out to be a story of global teacher hood.

“We don’t have control over the future” – but… shift in education during the Covid-19 pandemic

OLIVE project is future-oriented, raising the discussion about using technology in teaching, so the pandemic – even when shaking the norms of teaching – may have offered some forcing power to really elaborate on how technology can be integrated into teaching.

Continue reading “Behind OLIVE project – Faculty and facts “