When asked to picture a tropical marine environment you will probable imagine a tropical coral reef: bright, vivid colours, an abundance of dazzling fish, lovely warm waters and most importantly coral.

Yet tropical coral reefs are famously suffering from many threats, both human and environmental. These threats have caused mass coral deaths through the tropical seas. The coral reef cover in the Caribbean has declined from ∼50% in 1977 to ∼10% by 2001 (Gardner et al., 2003). And this phenomenon is not unique, with many other tropical reefs following similar trends.

In the face of these declines there have been shifts from coral dominated reefs to seaweed dominated reefs. In Jamaica, corals declined from more than 50% coverage in the late 1970 to less than 5% in 1994, with fleshy seaweeds coverage increasing to more than 90% at the same time (Hughes, 1994). Indeed, some tropical seaweeds have actually benefitted from coral reef declines caused by coral bleaching, hurricanes, disease and human activities including overfishing and eutrophication. This has allowed tropical seaweeds to increase in abundance, often becoming dominant in what used to be coral dominated reefs.

Bleached coral. Townsville. Queensland. Australia

In fact many scientists and policy makers interpret increases in seaweed as the single best indicator of reef degradation.

But do tropical seaweeds really deserve such a bad reputation?

Lobeweed (Lobophora variegata). El Hierro. Canary Islands. © OCEANA

Tropical seaweeds are often demonised, being credited to the degradation of coral reefs by competition and overgrowth. However tropical seaweeds can in fact play a valuable part in tropical ecosystems as well.

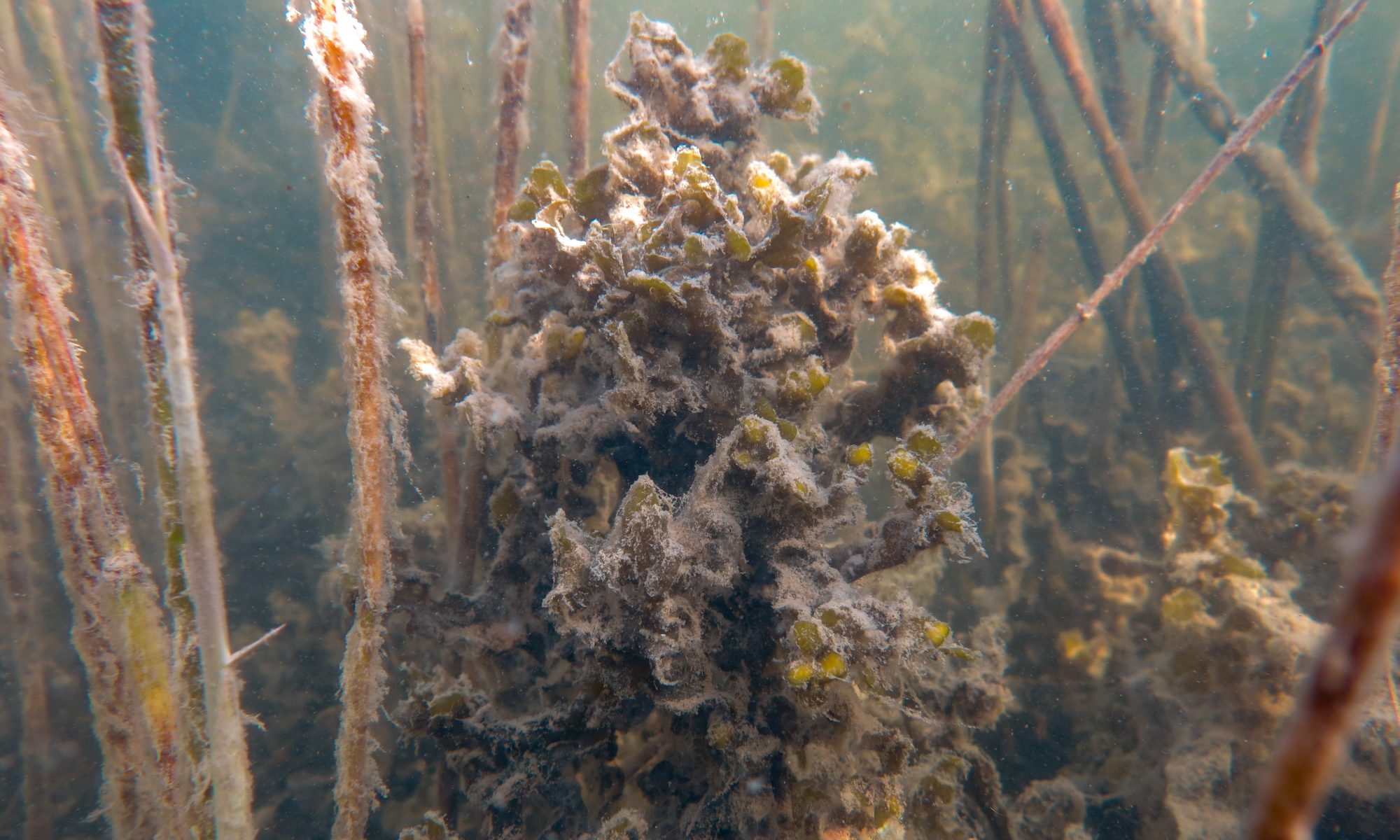

Tropical seaweeds are highly diverse, encompassing many species including larger canopy forming wireweeds (Sargassum) species to smaller, understory lobeweeds (Lobophora) and fanweeds (Dictyota). Many animals rely on tropical seaweeds as food sources or shelter, amongst other things. Various tropical fish, including frogfish and seadragons, can be seen to mimic seaweed as a form of camouflage. In fact the aptly named Sargassum fish, shows incredible resemblance to its drifting seaweed home.

Sargassum fish (Histrio histrio). Sargasso Sea. Atlantic Ocean.

Often seaweed reefs can be extensive in comparison to coral reefs. In Ningaloo (Western Australia) seaweed reef coverage was 46% compared to just 8% for coral reefs (Kobryn et al., 2011). Tropical seaweed reefs are especially common in coastal locations and can be considered one of the most prominent types of shallow water tropical habitats. Consequently these tropical reefs can play an important role within interconnected tropical seascapes.

But are all seaweed reefs equal?

Seaweeds have the potential to improve biodiversity, but some seaweed canopies can have far greater effects on diversity than others. Reefs dominated by weedy, low-stature seaweed; often associated with environments pressured by human activity or disturbance; lack the complexity required to support a plethora of plants and animals. On the other hand, seaweed reefs containing a mixture of canopy and understorey seaweeds and coral provide a high-complexity habitat that can support many levels of biodiversity.

Sargassum (Sargassum vulgare). Malta. (OCEANA/Photographer©LIFE BaĦAR for N2K)

Thus habitat quality; encompassing the coverage, density and canopy height; is important in influencing the range of plants and animals that a seaweed reef can support.

Fish recruits, including important fishery target species; have a much better survival in seaweed reefs with high quality canopies. Therefore more of these new fish recruits can join the adult populations in both coral and seaweed reefs. Consequently seaweed reefs with high quality canopies are much better at supporting fish populations, both within the seaweed reef and outside of it, compared to those with low quality.

So tropical reefs can, in certain circumstances, be beneficial despite their bad reputation.

Unfortunately, their commonness in coastal areas and the belief that they are best indicators for reef degradation has increased the risk that seaweed reefs are erroneously concluded to be a result of detrimental human activity rather than a natural component of a healthy ecosystem.

In seaweed reefs, if there is no evidence that a shift from coral to seaweed has occurred then they should be considered natural components of the seascape.

Brown Fan Weed (Dictyota sp.). Bare Island. New South Wales. Australia

In fact seaweed reefs can often be found on coastlines and remote reefs with low pressure from human activity, being an important part of the interconnected mosaic of tropical patch habitats. These reefs merit protection and deserve recognition as key components of the tropical seascape.

So not all seaweed reefs are the same: some are indicators of an unhealthy coral reef system though others are natural tropical habitats. We need to acknowledge the assets that complex seaweed reefs can be and protect them.

This post was based on the research of Fulton et al., (2019).

If you enjoyed this post you can find the article here:

Sources:

Gardner, T.A., Côté, I.M., Gill, J.A., Grant, A. and Watkinson, A.R., 2003. Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. science, 301(5635), pp.958-960.

Hughes, T.P., 1994. Catastrophes, phase shifts, and large-scale degradation of a Caribbean coral reef. Science, 265(5178), pp.1547-1551.

Kobryn, H.T., Wouters, K. and Beckley, L.E., 2011. Ningaloo Collaboration Cluster: Habitats of the Ningaloo Reef and adjacent coastal areas determined through hyperspectral imagery.