By Marika Pulkkinen.

During the last decades, the LGBTI (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgendered/transsexuality, Intersexed) movement and queer activists have focused on pragmatic issues such as same-sex marriage and rights for adoption for couples living in a same-sex partnership or marriage. The debates on these issues tend to center on questions of kinship: how do the current civil legislations around the world correspond to the reality in which many LGBTI people live? In biblical studies, the interpretation of specific passages that have been used to deny these rights have gained overwhelming attention.

Nevertheless, recent studies from queer hermeneutic perspectives have shifted in tone from apologetic to more descriptive, which in my view seems liberating. Not only the texts that have been used in these debates, but also other biblical texts are currently under examination. One possible way to read the ancient texts is to focus on the aesthetics from the embodied perspective. For instance, José Esteban Muñoz’s study Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009) aims at construing or imagining a utopic queer future that is built on the past reality of the LGBTI people. Muñoz formulates his scope in almost eschatological tones: “[q]ueerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. […] We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. The future is queerness’s domain.” (2009, 1).

This study can be seen as a counter force for Lee Edelman’s No Future. Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Duke University Press, 2004), which is also a study from a queer reading perspective. The study views the queer present as by definition lacking a future. Edelman criticizes heteronormative reproductive futurism. For him, “queerness names the side of those not ‘fighting for the children,’ the side outside the consensus by which all politics confirms the absolute value of reproductive futurism.” (2004, 3). Edelman uses the capitalized ‘Child’ “[…] as the emblem of futurity’s unquestioned value and purpose […]” (2004, 4).

In 2017 SBL annual meeting in Boston, the program unit of LGBTI/Queer hermeneutics chaired by professor Joseph A. Marchal (Ball State University) arranged a book review panel of Lee Edelman’s No Future, as well as an open call for papers reading the Book of Ecclesiastes from the perspective of queer experience and queer theory. The book of Ecclesiastes have been read from various queer hermeneutical perspectives (see, e.g., Jennifer Koosed 2006, cf. also the literature listed in her chapter in The Queer Bible Commentary). Particular attention has been paid to Qohelet’s “latent homosexuality” (cf. Frank Zimmermann, The Inner World of Qohelet, 1973). Taking a different path, Jared Beverly‘s presentation (Chicago Theological Seminary) explored Qohelet in dialogue with Lee Edelman’s No Future (2004), focusing on Edelman’s critique of “the (heteronormative) investment in the future that necessitates the sacrifice of (queer) present,” as Beverly put it. Qohelet is seen as lacking the view which is predominant elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible: a positive emphasis on the future through reproduction. Beverly sums up in his abstract that Qohelet’s “[…] perspective does not invest in the figure that Edelman calls ‘the Child’ because all of one’s investment in the future is ultimately futile anyway […].” Hence, Qohelet’s advice to enjoy the present (8:15) can be viewed in light of the tone of queer temporality.

The papers presented in the LGBTI/Queer hermeneutics section were firmly engaged in concepts used in the cultural studies as well as the recent phenomena and products of popular culture. In addition, the theoretical framework behind the papers was based on critical theory, semiotics, and poststructuralism. The discourse seemed to alienate a scholar like me who is more accustomed to take part in conversations of more textually (rather than theoretically) orientated approaches, but is also enough informed by the cultural gap between these approaches to not ask entirely naïve questions. This alienation prevented me from inquiring, e.g., how to locate a queer experience of parenthood? Are the LGBTI parents not part of “reproductive futurism”? Perhaps this kind of questions will be discussed more profoundly next year, as the program unit of LGBTI/Queer hermeneutics has a call for papers for formulating interpretive methods that emerge from the diversity of LGBTI/Q experience and thought focusing on kinship in SBL annual meeting 2018.

For further reading:

Jeremy Punt 2011, “Queer Theory, Postcolonial Theory, and Biblical Interpretation: A Preliminary Exploration of Some Intersectio” in Bible Trouble: Queer Reading at the Boundaries of Biblical Scholarship. Ken Stone & Theresa Hornsby (Eds.). Society of Biblical Literature: Semeia Studies. Atlanta, 2011, 321–341.

Jennifer L. Koosed, “Ecclesiastes/Qohelet” in The Queer Bible Commentary. Deryn Guest, Robert E. Goss, Mona West & Thomas Bohache (eds.) London: SCM Press, 2006, 338–355.)

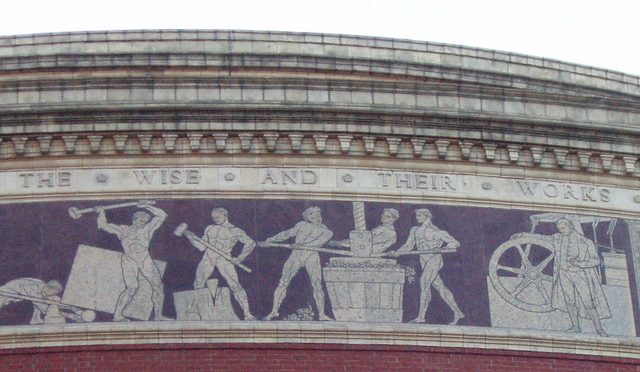

Cover image: Frieze on the Royal Albert Hall depicting Qohelet 9:1, by GeographBot: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frieze_on_the_Royal_Albert_Hall_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1430602.jpg.