Pääsiäisen alla Kirkko ja kaupunki -median esittämä #silmätristissä-kuvahaaste herätti lukijat hahmottamaan ristin kuvia ympäristöstään. Kampanja oli kekseliäs ja ehkä hieman provosoivakin, onhan uskonnollisten tunnusmerkkien pitäminen esillä ja niistä puhuminen tullut nykyaikana yhä kyseenalaisemmaksi. Pohjoismaisessa kulttuurissa uskontoa on kauan pidetty jokaisen yksityisasiana, ja nyt haluamme mielellämme soveltaa samaa yksityisyyden periaatetta myös muualta tuleviin kansalaisiin ja heidän uskonnolliseen ilmaisuunsa. Samalla tämä periaate kääntyy meitä itseämme vastaan: Keskustelemme joka vuosi soveliaisuudesta järjestää koulujen perinteisiä joulu- ja kevätjuhlia; kauppaketju poistaa etelämaalaisesta mainoskuvasta kirkontornien ristit, suvaitsevaisuuden merkiksi.

Keskustelu ei kuitenkaan ole uusi. Samoin oli 1500-luvun lopun Englannissa. Vuosisatainen roomalaiskatolinen perinne oli saanut väistyä protestanttisen kuningattaren tieltä, ja puritaanisimmat kannattajat halusivat uuden kirkon kieltävän myös ristin kuvan ja ristinmerkin. Moni vangittiin ja tuomittiin sääntöjen rikkomisesta. Runoilija John Donne (1572–1631), joka oli syntyperältään katolinen, otti kantaa ristikeskusteluun. ”Kristus itse otti ristin kantaakseen; / kuinka minä saatan tämän kuvan kieltää?” Donne kysyi runossaan.*

Uskova näkee vakaumuksensa tunnusmerkit joka puolella maailmassaan. John Donne tietää tämän myös: ”Kuka voi kieltää minulta vallan ja vapauden / levittää käteni ja olla niin oma ristini?” Donne kysyy edelleen ja jatkaa kuvaamalla, kuinka uimari jokaisella vedollaan muodostaa ristin, kuinka linnut taivaalla liitävät ristin muodossa, kuinka koko maailma pituus- ja leveysasteineen (tämä oli uutta tiedettä Donnen aikana) on toisinto ristin kuvasta. Donne ottaa runossaan jo neljäsataa vuotta sitten osaa #silmätristissä-kampanjaan.

Oma isoäitini oli herkkä merkeille maailmassa. Hän varoi visusti jättämästä aterimia, narunpätkiä tai tulitikkuja pöydälle ristiin — kuoleman merkiksi. (Tämä oli yleinen pahaenteinen uskomus hänen aikanaan. Minä kulutan ihmiselämän verran aikaa päästäkseni irti tuosta perimästäni taikauskosta.) Uskonnollisten merkkien voima on suuri, ehkä ne siksi pelottavat.

Mutta kuva ei kieltämällä katoa. ”Kuka voi peittää ristin, tuon, / jonka Jumala kasteessa minuun piirsi?” Donne kysyy. Samoin on kaikkien uskonmerkkien kanssa: pelkkä kuvan tai tunnusmerkin piilottaminen ei poista vakaumusta. Todellinen suvaitsevuus ja yhteisymmärrys voidaan saavuttaa ainoastaan hyväksymällä uskon rauhanomainen ilmaiseminen, jokaisen oman vakaumuksen tarinan kertominen. Uskon ulkoinen tunnusmerkki, oli se sitten riipus, päähine tai tapa tervehtiä vastaantulijaa, ei pohjimmiltaan ole ulkoinen uhka vaan sisäinen oman uskon vahvistus.

”Tämän ristin menetys / olisi minulle uusi risti,” John Donne sanoo runossaan ja jakaa samalla myös useiden eri uskoa tunnustavien nykyajan ihmisten tunteen. ”Mikään kärsimys, / mikään risti ei ole niin raskas, kuin olla sitä ilman.”

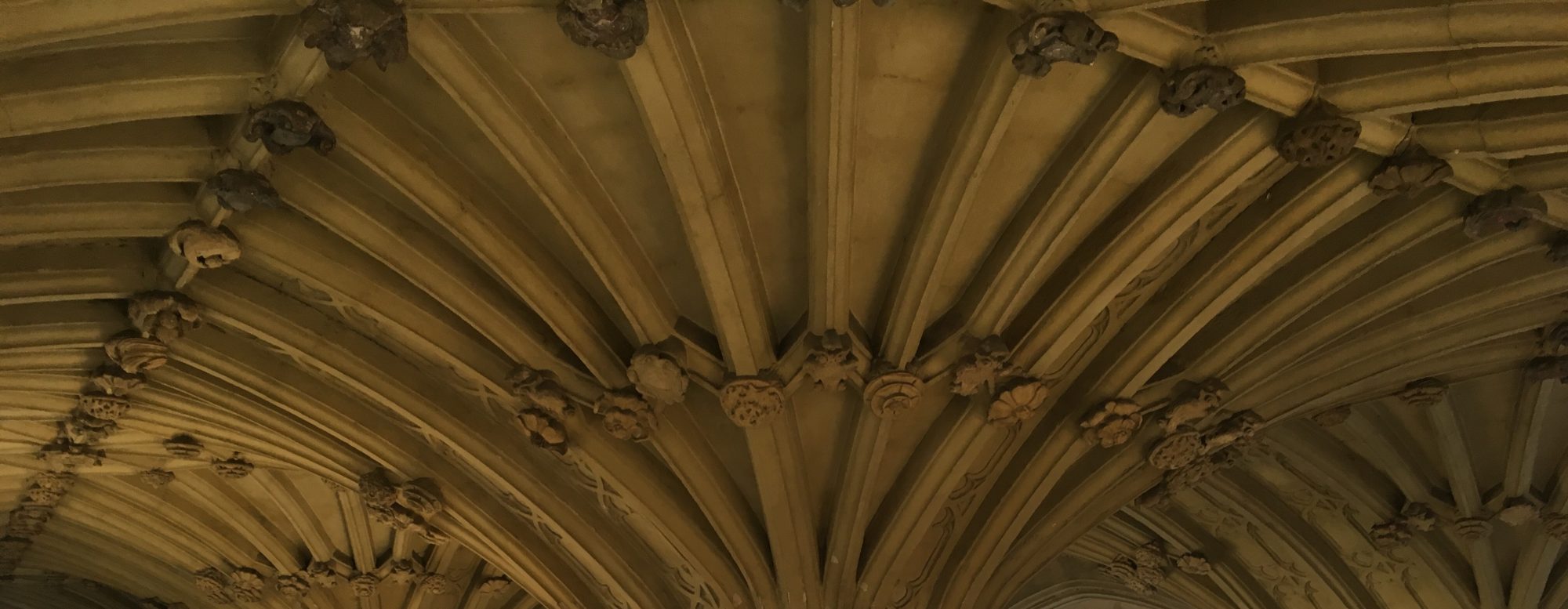

”Marttyyrien risti” kadussa Englannissa Oxfordin Broad Streetillä vuosina 1555–56 teloitetun kolmen protestanttisen piispan muistoksi.

*John Donnen runon ”The Crosse” lainaukset suomennettu tätä tekstiä varten (MS).