Easter and Passover are of the times of year when historical and scientific explanations seek to find ways to support, or contradict, magic and faith. Numerous documentaries are aired on Western television during the holidays, with the purpose to see the Judeo-Christian narrative within the context of historical evidence and scientific proof. Validity and belief lock horns. Religious texts are set against historical documents and tried through scientific process. When could the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn really have created the illusion of a great star? What was the role of Egypt, for the people of Judea, and for the family of the carpenter Joseph? What did Caesar Augustus really decree? What was the plan of Herod? – What happened that Easter around AD 33 in Jerusalem?

The twilight zone between the two parties of the debate is the vast semantic field of the metaphor. Ancient prophesies can turn into substantial future events, or they can be seen realised in symbolic form. The “great light” (Isaiah 9:2) can be searched as a great “star in the east” (Matthew 2:2), or as illumination on a broader scale. Where the blood of a slaughtered lamb as a sign on the door-post saves from illness and the death of the oldest child (Exodus 12:6–11), the blood of the metaphorical sacrificial lamb keeps returning as a life-giving force in Christian narrative thousands of years later.

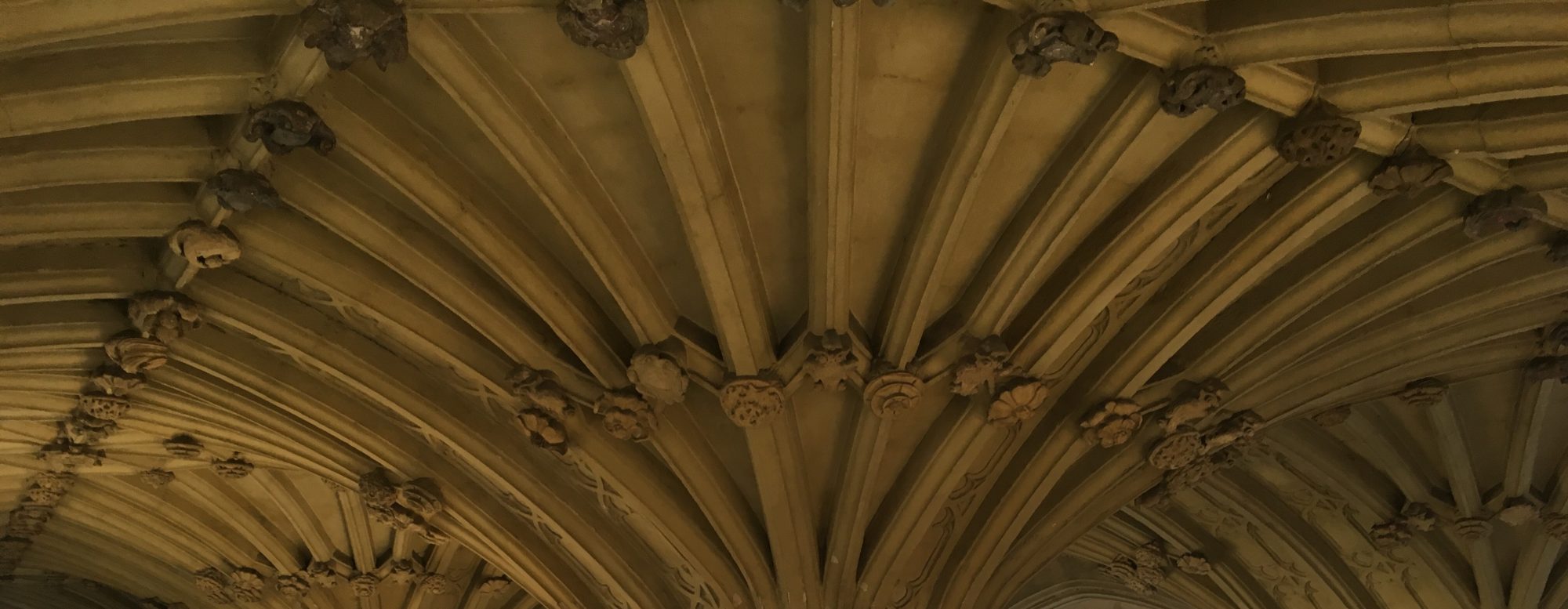

The poet John Donne (1572–1631), together with the other Metaphysical poets, developed the art of the poetic conceit into the most prominent composition of prophecy, metaphor and image. On Good Friday 1613 (then, too, on the 2nd of April, like this year), Donne returns to one of his most favoured puns, expanding and exploding it into a most profound Christian metaphor – and into a rather intriguing philosophical image. While riding Westward, Donne writes, were he to turn around and face East, he “should see a Sunne, by rising set, / And by that setting endlesse day beget;” (ll. 11–12). The sun rises from the east, yet this is also where, in the narrative of the Christian Donne, the Son on God is raised on the cross to his death; by dying, then, he is creating everlasting day — life — to mankind. While the full interpretation of redemption and mercy is restricted to a Christian reading, the ”Cosmographers” (whom Donne tempts in another poem, ”Hymne to God my God, in my sicknesse”, l. 7) must find the image rather ingenious, too.

* The quotations, as well as the image of the poem, are from the 1921 edition of Herbert J.C. Grierson’s Metaphysical Lyrics & Poems of The Seventeenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press), the centenary of which is celebrated this year as one of the key inspirations for the revival of Donne and the other Metaphysical poets for the modern reader.