By Anna Kangas, Helmi Lappalainen-Imbert, Eveliina Piispanen, Juliette Rose

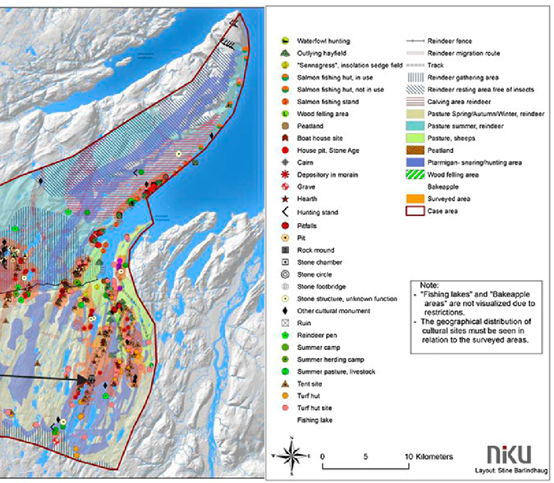

There is no other place in Finland than Kilpisjärvi that has similar differences in altitudes combined with moist marine climate traits and rare soil minerals. There, in the northernmost part of Finland, nature has a central role in the livelihoods of people. This area is also home to 177 reindeer herders, of which 45% are Indigenous Samí people, and 10 000 reindeer. Reindeer husbandry provides meat and supports traditional herding, which is an important part of the local culture. In traditional herding, reindeer can gallop freely between pasture lands. In this blog we will discuss how reindeer herding affects the local ecosystems. The area is also facing new challenges due to global warming, as the temperature in the Arctic is rising significantly faster than the global average.

Endangered flowering plants and reindeer herding

Kilpisjärvi area is well known for its colorful flowering plant species, many of which are nationally endangered. For example, the yellow flowers of glacier buttercup (Ranunculus glacialis spp. glacialis), cannot be found anywhere else in Finland. Also, strolling reindeer herds are a part of the Kilpisjärvi landscape. How do the endangered small plants and the semi-domesticated plant eating and ground trampling ungulates, get along?

While reindeer grazing is an important factor for maintaining some fell habitat types, nationally grazing is also defined as a cause of endangerment for 21 biotopes. Further, there isn’t yet comprehensive knowledge on how reindeer herbivory affects single endangered species found in Kilpisjärvi. Some studies indicate that reindeer grazing could be beneficial for small growing plants, as mammals remove taller competing biomass from the growing site. On the other hand, some species, like the buttercup, are well known to suffer from trampling and dining of the herds.

Pasture lands facing climate change

The ongoing climate change is altering the ecosystems of Kilpisjärvi. Rain and temperatures are also expected to increase in winter more than in summer, and this will cause changes in snow and ice conditions as well as in vegetation. The warming climate shifts the tree line and the distribution of plant species northward to higher altitudes. This causes tundra and fell ecosystems to be replaced by birch forests and coniferous forests. As a result, pasture lands suitable for reindeer may decrease and become fragmented.

As spring is expected to start earlier and winter later, and snow cover is expected to be up to 40 % thinner by midcentury, it can benefit the herders and increased rain boosts plant growth. Local herders have already noticed a shift from lichens to vascular plants. In addition, increased pollution may reduce the quality of forage plants. Especially lichens are sensitive to air pollutants. Reindeer can be categorized as opportunists, meaning that they can feed on a wide range of plant species. Therefore, reindeer may be able to adapt to the changing vegetation at some level.

Increased frost and thaw cycles together with heavy rain-on-snow-events can cause ground ice to block access to winter food and cause mass starvation in reindeer populations. Heavy rain events can cause flooding and drown reindeer. Warming temperatures can also introduce new species, diseases, and parasites to the area, adding stress to reindeer.

Increase in predators

Brown bear, gray wolf, wolverine, and Eurasian lynx are the main four large carnivores that prey on reindeer in Finland. Prior to 1990, these animals were hunted without limitation to avoid reindeer predation causing large carnivores to almost disappear. Since 1990, hunting has been regulated to preserve them. Today, predator populations are increasing.

However, reindeer herders do not appreciate this comeback of large predators, since it increases predation and threatens their traditional livelihood. In the Käsivarsi district, 3-5% of reindeer are killed annually. In Kilpisjärvi wolverine dominates the damages with 621 reindeer found killed in 2021.

Loss of reindeer due to predation is financially compensated. Herders get the value of carcasses they find, which costs time and money and is not considered within the compensation. This has made herders feel that the compensation is inadequate, as in addition the value of their breeding practice is not compensated either. One solution could be to compensate reindeer losses according to the territory occupied by predators, which would allow herders to spend more time protecting the herds instead of assessing the damage. However, this idea is not approved of by the herders. This means that predation on reindeer may continue increasing, and some herds may disappear in the future.

Herders facing the changing environment

To cope with the changing environment, herders need to create successful coping strategies that ensure the economic and cultural viability of their livelihood. Examples of strategies could include intensifying pasture use and diversity, using supplementary feeding, using enclosures, or increasing control over their herd to ensure herds’ safety, and this also helps to limit the damage done by predators. Repellants and anti-parasite medication will also be necessary to ensure the survival of the populations.

The future of reindeer herding in Kilpisjärvi

Reindeer population has a significant impact on its environment. A unique area like Kilpisjärvi draws the interest of many different groups of people with different points of view on reindeer. For some actors, herding is an important traditional livelihood, whereas for some it is seen as a potential threat for plant diversity and endangered large carnivores. What is the future of reindeer herding, when for example climate change induces changes in pasture conditions? Will indigenous people be able to continue their activity? To help communities to adapt to changing conditions, regulation policies should ensure profitability and diversification of the herding livelihood. Policies should help to protect the culture and traditional knowledge, reorganization of the management systems and support herding practices to be more sustainable. Currently, the Kilpisjärvi community is, for example, lacking a consensus on the effects of grazing on regional vegetation. More objective research would be needed to support the local community to work together for a sustainable solution that acknowledges the socio-cultural and biological diversity of the area. Decisions must be taken now, and all the voices should be heard.

References:

Rantanen, M., Karpechko, A. Y., Lipponen, A., Nordling, K., Hyvärinen, O., Ruosteenoja, K., Vihma, T. & Laaksonen, A. 2021. The Arctic has warmed four times faster than the globe since 1980. Physical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-654081/v1

Horstkotte, T., Utsi, T. Aa., Larsson-Blind, Å., Burgess, P., Johansen, B., Käyhkö, J., Oksanen, L. & Forbes, B. C. 2017. Human-animal agency in reindeer management: Sami herders’ perspectives on vegetation dynamics under climate change. Ecosphere. 8(9): 1–17. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.1931

Paliskunnat. 2022. Kilpisjärvi. Reindeer herders’ association. Online document. https://paliskunnat.fi/reindeer-herders-association/cooperatives/cooperatives-info/kasivarsi/

Metsähallitus. 2019. Käsivarren erämaa-alueen ja Annjaloanjin suojelualueen hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma. https://www.metsa.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Kasivarsi_hks_vahvistettavaksi-1.pdf

Rasmus, S., Kojola, I., Turunen, M., Norberg, H., Kumpula, J., et Ollila, T., 2020. Mission impossible? Pursuing the co-existence of viable predator populations and sustainable reindeer husbandry in Finland. Journal of Rural Studies, volume 80, p. 135-148

Turunen, M., Soppela, P., Kinnunen, H., Sutinen, M.-L. & Martz, F. 2009. Does climate change influence the availability and quality of reindeer forage plants? Polar Biol. 32: 813–832. doi: 10.1007/s00300-009-0609-2

Turunen, M., Rasmus, S., Bavay, M., Ruosteenoja, K & Heiskanen, J. 2016. Coping with difficult weather and snow conditions: Reindeer herders’ views on climate change impacts and coping strategies. Climate Risk Management 11:15-36 https://www-sciencedirect-com.libproxy.helsinki.fi/science/article/pii/S2212096316000036?via%3Dihub