Sustainability of cities can be measured in multiple ways, and recently, the limelight has been claimed by environmental sustainability, in particular the role of cities in the forefront of climate change actions. However, the definition of sustainability encompasses also economic, social, and sometimes also cultural aspects, and the role cities play in the two latter roles has been less actively discussed.

Gray and socially isolated cities?

The literature on the social implications of dense urban environments is rather complex and even contradictory – the most classical arguments claim that there is an inherent tension or paradox between the compact city and people’s desire for a spacious, green, and quiet environment. In addition, many sociological classic theories see urban areas as environments with superfluous relationships failing to satisfy people’s social needs.

However, were these theories accurate or not, it is still evident that in the current world with growing urban population, planning for the typically sized hunter-gatherer society is not possible. Thus, for example, the questions of how to combine nature with urban built environments, and what kinds of urban structures support our wellbeing in densifying cities, become ever more relevant.

Studying wellbeing and happiness in cities

Subjective wellbeing, measured by asking people how happy or satisfied they are, is one possible way to compare social sustainability of different types of areas. It is a good candidate for evaluating urban social sustainability as it is known to correlate with many aspects relevant in the spatial scale, such as social equity, accessibility, and safety. In recent years, subjective wellbeing has also aroused interest as a policy goal, that highlights the need for research around the subject.

For the urban dwellers, the conclusions made in the realm of geography of wellbeing can be a bit depressing. It has been often reported that urban dwellers are less happy than their rural counterparts. This seems to hold true especially in the biggest cities and largest urban centres. However, there are also more unambiguous results and contradicting views on the density-happiness relationship.

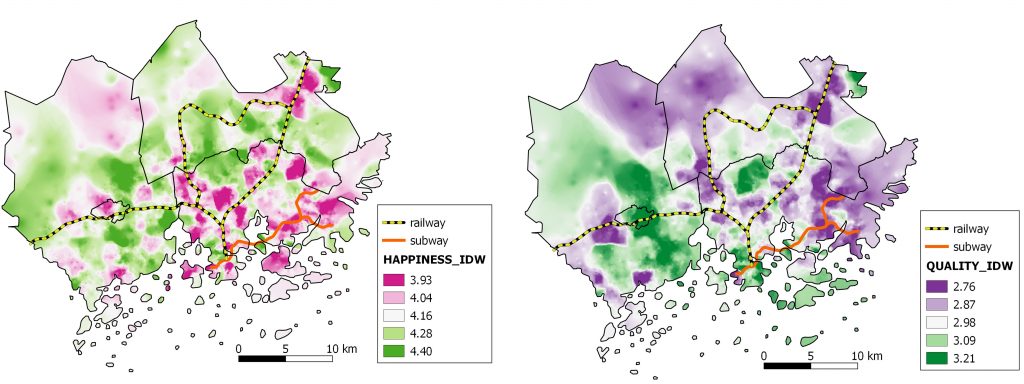

Our recent results about the perceived happiness and quality of life of urban dwellers in Finland are also intriguing: for example, central pedestrian zones were related to higher quality of life, but to lower on average happiness. Happiness, on the other hand, was highest in the car-oriented zone, which is the least urban, or in other words, the most suburban and least dense of the zones studied in our paper. Thus, the measure of wellbeing used had a salient role in how the relationship between density-wellbeing appears to be.

The question about the happiness or unhappiness of urbanites requires further research. New results have for example claimed that happiness in cities is a question of generation: in US, the Millennials are happier in cities while earlier generations are happier outside cities. The underlying reason for this can be speculated to be in different values, calling for further research also on the value differences between different living environments.

Is happiness a relevant urban policy goal?

Focusing on density-subjective wellbeing relationship is a good start, but urban areas are more than densities, and same density can manifest itself in many forms. Other factors found to enhance wellbeing that can be affected by urban policies include for example accessibility, safety, commuting time and air pollution. Furthermore, many of these have also direct health implications, making them ever more important targets when aiming to impact the wellbeing of urban dwellers. It is also rather universally agreed that social capital, and social trust in particular, are more important for subjective wellbeing than spatial variables per-se, and thus it is also essential to think how policies can leverage these especially in the urban environments.

However, all studies based only on subjective measures have their problems, be they related to methods and their use or people’s biases when answering such surveys. Thus, even though maximizing happiness of city dwellers might sound a tempting goal for policies, it should be treated with some caution and the actual choices of people, in addition to their opinions, need to be kept in mind – these two can be radically different.

Sanna Ala-Mantila

Sanna Ala-Mantila is Assistant Professor in Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science (HELSUS) and in the Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences in the University of Helsinki.

References and further reading

Ala-Mantila, S., Heinonen, J., Junnila, S., & Saarsalmi, P. (2018). Spatial nature of urban well-being. Regional Studies, 52(7), 959-973.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., & Valente, R. R. (2019). No urban malaise for Millennials. Regional Studies, 53(2), 195-205.

Bramley, G., & Power, S. (2009). Urban form and social sustainability: the role of density and housing type. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 36(1), 30-48.

Photo by: Ilja Smelich