Yesterday I attended the inaugural in person meeting of RESET (Resilient and Just Systems) at Helsinki University which aims to bring together different academics toward coproducing research as part of resilient and just socioecological change.

I thought it worth summarizing my experiences of coproduction as an invitation to other researchers to do likewise and hopefully this can help us better coproduce work going forward. Particularly as my current work as part of RESET involves coproduction.

As is noted within, these are not necessarily flagship examples of coproduction or even fully formed examples but instead reflect a few of the different learning points I have encountered toward my intention of coproducing more.

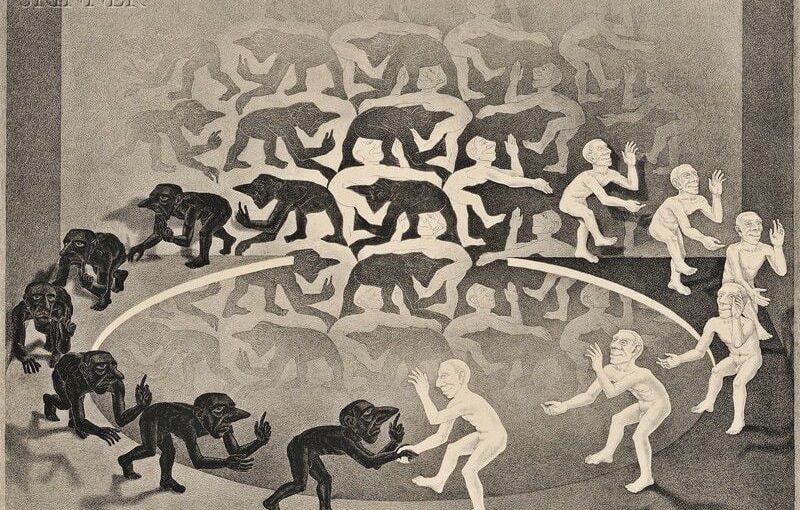

(1) Cocreating art across disciplines:

As an undergraduate my peers and I organised multiple seminar series with fellow students and academics from different backgrounds to explore ‘the elephant in the room’. We were in a university department comprising both anthropologists and wildlife conservationists, however, there did not seem to be as much meaningful cross-disciplinary collaboration as we had hoped. Whilst these seminars, that imitated our academic superiors, involved a lot of learning and were interesting, it was when we turned our hand to art that something really seemed to catalyse. We crafted a sizable elephant in front of the department building that everyone could contribute to creating. We then placed the sculpture in the middle of the department building where people from both disciplines would have to encounter it. It remained there for over a year. Over the following years a funding pot for anthropologists and conservationists was created to support collaboration on mini research projects. In addition the department introduced a new disciplinary branch in the form of Human Ecology and Human Geography, that were intended to bridge the gap we had perceived. I taught Human Ecology as an Associate Lecture as part of this.

What I learnt about coproduction:

Collective creative and playful interventions can provide powerful and memorable moments that manifest the social complexity inherent in collective environments. Specifically in a totemic, iconic and tangible form that represents something ungraspable by tidy, linear and rational argumentation and thus reaches outside of siloed pigeonholes. In sum, icons can say something more than science about science that connects people with science.

(2) Collaborating across opposition

On the side of my doctoral research I developed a hypothesis to do with corvid pest management in my fieldsite, but realised I was not equipped to test the hypothesis by myself. So I approached a friend who was an ornithologist to ask if he would team up with me. He also invited a geneticist from his Faculty in Veterinary Medicine who then also invited one of their students. Together we tested the original hunch I had. Crucially it would also require the organisation I was studying (a hunting federation) to participate with academics that belonged to an organisation (Save the Birds) that was in opposition to it. At the beginning of my PhD I tried something similar and failed in this endeavour as I tried to bring wildlife conservationists and hunters together around a research agenda they did not understand, rather than in this case around a question that required us all and peaked everyone’s interest. At the very least it was focused on pests which was a less contentious topic as it focused on mutually unwanted animals.

What I learnt about coproduction:

Formal plans and intentions might not work, but paying attention to what is possible means initial failures led to successes in co-authored research that had specific policy implications.

(3) Giving Back Research

As is now customary in social anthropology, after I finished my doctorate I created a slimmed down more accessible version of my thesis and gave copies to my informants (mostly hunters) and talked them through it and gathered their feedback and responses.

What I learnt about coproduction:

Informants were interested in things I had not even considered, more in their social dynamics of having research about them introduced to their social milieu and how my work played into local politics of representation. Whilst this was not technically coproduction it taught me to be more aware of how research as an object rather than its content per se, has a kind of agency when introduced to a social context.

(4) Public-Private Partnership Engagement

I was employed alongside another junior researcher to deliver a 2 year project designed by 2 senior researchers, all from disciplines I was not trained in. The project involved producing future scenarios through spinning together a partnership’s different stakeholder insights. Ultimately a report was written, but the partnership were not invested in the project and did not understand its purpose as it was not articulated on their terms, but instead acted as a research trophy on the private sponsor’s wall. In addition the existent partnership we engaged with had not itself developed any meaningful basis itself to engage with researchers.

What I learnt about coproduction:

If you are going to do a coproduced research project then you have to do the groundwork. Either take time to cultivate a shared understanding and interest or be sure to engage with a partnership or set of organisations that has already developed a way of working and to see where they are at and how your contribution as an academic can be of service to them on shared terms.

(5) Supporting existent coproduction

I joined a team producing research and co-directing a film where the protagonists and the researchers had become equal members of the team, particularly in the making of the ethnographic film. Initially I noticed that they were missing a new voice to bounce off and someone to organize engagement with their film so I gently offered to play that role. This led to an ongoing collaboration exploring the social context of tuberculosis outbreak through explicitly coproduced research.

What I learnt about coproduction:

Coproduction can emerge iteratively from what was once an individualized predefined research project. I also learnt that coproducing a narrative can be a very therapeutic endeavour for non academics involved, as often people do not have the facilities, platform or confidence that their stories are worth hearing and have authority.

Hence coproducing a research based film enables this rationalization of messy reality into a somewhat linear narrative, without losing context, whilst also being accessible and with some academic authority.

(6) Supporting organizing

I belong to a union that was approached by migrant care workers facing exploitation. I established rapport by supporting events, cooking, helping with flyers, building a website etc. It was patently clear that without addressing the working conditions of social care workers all of the health challenges they worked on are going to suffer. As an academic working in public health it became obvious that the key determinant of many health conditions is dependent on the working conditions of care workers. So I decided to play a supportive role in helping them organize as a union and fight for better working conditions whilst also reaching out and introducing them to other organisations that could support them in other ways.

What I learnt about coproduction:

Coproduction is not simply about making research outputs together. Instead the question becomes ‘what life is it that we want to coproduce, lets create that, yes its difficult, but that is where we are going to start and to achieve that means getting organized and discovering collective power’. As a researcher it is for me to identify what the research needs are that can be met in this process and bringing an academic perspective and labour to that.

(7) Resisting misuse of coproduction

As part of an underground emergency response committee I was asked if I would provide some key tactical support for a local community who were losing their dental practice. This was not needed in the end but I ended up acting as a spokesperson and running the meetings with the national authority responsible for having shut their dental practice.

What I learnt about coproduction:

As a researcher simply being in these contexts introduces you to the realities of what is happening and enables you to theorize a topic in a grounded way. But most importantly in this context the national authority tried to use the language of coproduction to say they wanted to work with the local community to find a solution. But in fact, because I was there on the ground I could witness that at no point did this authority budge and instead continually expected the community to fit into their criteria, and even when the community did so, they were offered absolutely no innovative ideas or help in return. In this case coproduction was used to make a situation sound better than it was and placate people, which is why it was ultimately rejected by the community, at my suggestion, as a descriptor of what was happening.