We eat, drink and game for a number of reasons: in order to fill up time, to manage stress, to dampen emotions, to punish ourselves – or just to create space for fun activities in our lives. This is our prerogative as prosperous people in consumer society. Our behaviour is supported by commercial promises, by a seemingly endless availability of products and consumption opportunities, by the attractions of defining and understanding ourselves through acts of consumption. At the same time, these very same societies are involved in a process of negotiating the limits for what are defined as excessive and problematic variants of these behaviours. This is the research focus of the University of Helsinki Centre for Research on Addiction, Control and Governance (CEACG) – a research group founded by professor Pekka Sulkunen.

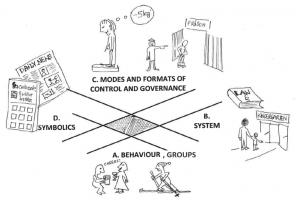

Figure 1. below is a simplified illustration the CEACG-research in four overlapping dimensions. These dimensions are basic building blocks for understanding governance of people and behaviour distinguished as matters to be transformed, normalized or prevented by (collective) interventions of some sort. Dimension A. concerns behaviours and people viewed as ‘the governed’; B. concerns system structures and institutions in which we operate when we address these matters; C. concerns the modes and formats of control and governance aimed to prevent or change behaviour; and, D. concerns the symbolic articulation of what the problems are all about and how they should be dealt with.

In the CEACG-research, all dimensions of Figure 1. are seen as connected, even if research tasks have typically come to emphasize the different dimensions to different degrees. Comparisons between countries and systems have been of special importance as these offer explanations to different types of setups and relations. Many times, the cross-country comparisons have been decisive for drawing conclusions regarding what the different policy and governance alternatives offer.

Figure 1. The construction of (A) ‘the governed’, through (B) frameworks of a system, its (C) modes and formats of governance and control, and all of this as part of a space provided by (D) cultural constructs of realities (Hellman 2015).

HABITS AND ADDICTION

In its simplest everyday sense, the concept of habit refers to action that is common practice, custom, convention, mannerism or routine. These are some of the words in the first two lines of the definition provided by the Collins Compact Thesaurus online dictionary. The third line lists synonyms with a more negative ring to them: ‘addiction, dependence, fixation, obsession, weakness’. The word ‘habit’ is interesting precisely because it covers both of these aspects: habit as ‘habitual’, as repetitive action, as a typical way of doing and being, but also habit as in repetitive behaviours that are often viewed as problematic in one way or another. This latter cluster of significations is often attached to social and health-related potentially problematic behaviour such as drinking, smoking, eating disorders, drug use and gambling (see e.g. Fraser et al. 2014).

Substance use, smoking, food intake, gambling, and other potentially addictive and problematic repetitive practices are interesting behaviours, not the least because they often start out in joyful, pleasurable and stimulating leisure activities but are known to cause problems in their widespread, excessive or compulsive variants. Thus, a shift in signification occurs along the way as the habit intensifies and accumulates — a shift which Pekka Sulkunen has framed as a shift in semiosis (Rantala & Sulkunen, 2012; Borch 2013)

Habits are thus understood as both voluntary and involuntary, changeable and constant. In the signification of voluntary choices, habits are viewed as preferred among other kinds or modes of activities by autonomous people in consumer society. Seen as versatile the habits automatically also entail ideas of adjustments, ways of controlling or restraining them. By some sort of decision-making and power exercising outside or inside the concerned individual the behaviour is envisioned as normalized or neutralized in a desirable direction (Jager 2003). At the same time, habits very much confine autonomy: habits control perceptions by limiting what we are exposed to and what we integrate into our ways of thinking. They are destined by cultural and consequential circumstances and based on interaction of experience, human proclivities, and the social and natural environment that are also affected by social processes (Todorova 2014). Some problematic habits are difficult to control as they are strongly conditioned and upheld in cultural grammar and societal rationales.

GOVERNANCE AND GOVERNMENTALITY

The study of lifestyle-related policies in a welfare state framing presents researchers with many tensions regarding societal priotitisations between different worths and principles. In welfare societies, typically, prosperity is high enough both for the exercise of grand consumption and for the existence of systems and institutions for preventing and dealing with the problems that arise from grand consumption.

The crossing of the grey area in the middle of Figure 1. in terms of tying rationales and ideas to social interventions would not be possible without discerning the ways in which governance is integrated in humans, institutions, culture, and, the organized practices (mentalities, rationalities, and techniques) through which subjects are governed (see Shah et al. 2007). One of the most crucial theoretical links for this purpose has of course been the Foucauldian concept of governmentality.

The governmentality literature has been important in facilitating a conceptual bridge between conceptions of what individuals and populations do in relation to logics of adherent modes of control and governance. Governmentality theories allow for a manifestation of the fact that habits and lifestyles cannot be understood without an understanding of the rationales underpinning their regulation. The accountability of collective action must be formulated within certain understandings of what the problems imply for society.

Traditionally, when patterns of behaviour are tagged as societal problems an orientation back onto the right path is envisioned through the exercise of some sort of pastoral power that guides people’s conduct as members of a population organizing them as a political and civil collective in the same way as a shepherd who cares for his flock (see Foucault 1982). Strategies such as warning texts on packs of cigarettes or alcohol taxes are typically justified and carried out with a view of a collective responsibility of the health and social well-being of the flock.

A crucial claim in the governmentality literature has been that modes and rationales of pastoral governance are changing. The governmentality research has continued to develop its core theoretical concepts related to lifestyle governance, for example in terms of technologies of self, lifestyle politics, biopolitics, and neuropolitics – all highly topical in a digital and global era (see e.g. Mayer 2015; Rose 2009).

THE MEANING-MAKING OF LIFESTYLES

In order to become a target of prevention and policy strategies, habits and behavioural patterns must become widely recognized and tagged as problems. The concept of lifestyles holds great relevance for understanding his approach to the study of cultural signification. Lifestyle is ‘a style of life’, a typical way of being and acting over time. The ‘style’ may depend on any possible relevant circumstance, but what it means needs to be spelled out. And the ways in which it is spelled out will inevitably attract the interest of a semiotician.

One can perhaps say that in the social sciences the most important meaning-based logic of how ‘style’ is articulated has thus far been the one of uneven resources attached to status and power in society. Roughly speaking one can see two main social scientific research domains concerned with the focus of unequality dimensions of lifestyles. The epidemiological paradigm typically maps socioeconomic factors correlating with alcohol use, while the dominating sociological traits are concerned with consumption and status in the field of consumption, culture and leisure.

The closest concept that I find that could describe the focus of inquiries concerned with a cultural grammar of lifestyles illustrated in Figure 1, is the Foucauldian term of dispositif (Foucault, 1980). It refers to a sort of network of institutional, physical, and administrative mechanisms and knowledge structures, which enhance and maintain the governing ontologies and adherent exercise of power in different matters. In the question of lifestyle politics, the dispositif can be seen as tied to master narratives of what contemporary life should contain and bring about (see e.g. Fraser et al. 2014; Mayes 2015). The dispositif changes with different emphasis on its different parts in line with changes in attitudes, societal prioritisations and preferential explanations on the concerned matters.

PUBLIC HEALTH AND PUBLIC SECTOR RESEARCH

Public health and epidemiology – and lately also psy sciences — are the knowledge resources and frameworks most often applied in policy-making concerning addictions and lifestyles. These have typically exposed associations between certain habits such as smoking, nutrition, alcohol, on the one hand, to health status, levels of mortality, and societal costs of ill health, on the other. Globally speaking, this kind of research can be seen as the mainstream knowledge production underpinning societal action aimed at reducing lifestyle-related burden of disease and encouraging wellbeing among populations (Hellman et al. 2016). It is simply not possible to perform social scientific research in the area of addictions and lifestyles without being familiar with this literature.

As a concept public health functions both as a descriptor of a status of health among populations (‘the health of the public’), and as a descriptor of an approach (‘seeing health issues on the level of populations’). The latter connotation especially embeds the field’s aims to deal, prevent and manage diseases, injuries and other health conditions through surveillance and through promotion of healthy behaviours, communities and environments. The institutionalized and publicly funded so called ‘sector research’ concerning lifestyle problems have in the Nordic countries been a natural part of the welfare project. In Finland, the most famous public research-based public health project has no doubt been the flagship North Karelia Project, which was launched in 1972, in order to reduce the exceptionally high coronary heart disease mortality rates in the North Karelia by adjustments of nutrition, smoking, physical activity, use of alcohol and psychosocial stress.

The new uses of psy-concepts in significations of societal phenomena, such as the addiction concept, has invited social scientists to incorporate a view on societies as organisms plagued with ‘social pathologies’ (see Furedi 2004). From the point of view of lifestyles that violate social norms and have a negative effect on society the meltdown of a system serves as a justification for controlling and adjusting breakages with normal and normative ways/styles of life. In their extension the social pathologies typically connote some sort of risky transgression such as in the case of illicit drug use, or a moral decay of society caused by pathological debt or overweight. Something is wrong in parts of the organism and it needs to get fixed in order for the entity to work.

REFERENCES

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical inquiry 8(4), 777–795.

Fraser, S., Moore, D., & Keane, H. (2014). Habits: remaking addiction. Palgrave Macmillan.

Furedi, F. (2004). Therapy culture: Cultivating vulnerability in an uncertain age. Psychology Press.

Hellman, M., Berridge, V., Duke, K. & Mold, A. (2016). Ownership of addiction: variations across time and place. Concepts of Addictive Substances and Behaviours Across Time and Place, 1.

Jager, W. (2003). Breaking bad habits: a dynamical perspective on habit formation and change. Human Decision-Making and Environmental Perception–Understanding and Assisting Human Decision-Making in Real Life Settings. Libor Amicorum for Charles Vlek, Groningen: University of Groningen

Mayes, C. (2015). The Biopolitics of Lifestyle: Foucault, Ethics and Healthy Choices. London: Routledge.

Rantala, V. & Sulkunen, P. (2012). Is pathological gambling just a big problem or also an addiction? Addiction Research & Theory 20(1), 1–10.

Rantala K. & P. Sulkunen (2006) Projektiyhteiskunnan kääntöpuolia. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Shah, D. V., McLeod, D. M., Kim, E., Lee, S. Y., Gotlieb, M. R., Ho, S. S. & Breivik, H. (2007). Political consumerism: How communication and consumption orientations drive ‘lifestyle politics’. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 611(1), 217–235.

Todorova, Z. (2014). Consumption as a Social Process. Journal of Economic Issues 48(3), 663–678.