Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cobalt and Artisanal Mining

Text by Saara Hurmerinta

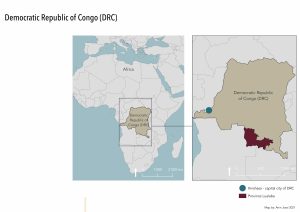

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of natural resources including minerals such as cobalt and copper, hydropower potential, significant arable land, immense biodiversity, and the world’s second largest rainforest (The World Bank, 2021). Mineral extraction is the backbone of DRC’s economy with copper and cobalt alone accounting for 85 percent of its export (Baumann-Pauly & Cremerlyi, 2020). However, this has not made DRC and its people rich, in fact, DRC is one of the poorest countries in the world. Of the 90 million Congolese (Statista, 2021) 73 percent live below the international poverty rate of 1,90 dollars a day and 43 percent of children are malnourished (The World Bank, 2021). It also lacks many basic services with only 16 percent of Congolese having access to clean drinking water, 18 percent finishing secondary school and the electrification rate being only 6 percent (Sovacool, 2019). The heavy reliance on one industry alone, especially one as susceptible to price changes as mineral extraction, makes the economy of DRC extremely vulnerable.

Cobalt

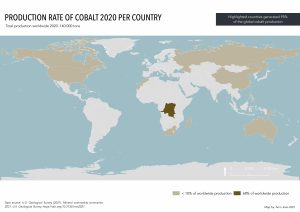

DRC is the largest producer of cobalt in the world currently accounting for 70 percent of the world production and has half of all known reserves (U.S. Geological Survey, 2021) (see map below). Currently about half of all cobalt produced is used in rechargeable batteries of electric vehicles, smart phones, and laptop computers (Banza Lubaba Nkulu, Casas, L, Haufroid, De Putter, Saenen, Kayembe-Kitenge, Musa Obadia, Kyanika Wa Mukoma, Lunda Ilunga, Nawrot, Luboya Numbi, Smolders, & Nemery, 2018). With the advance of green technology and electric cars, the demand for cobalt, an essential mineral for lithium-ion batteries, has increased dramatically and is expected to grow four-fold by 2030 (World Economic Forum, 2020). However, cobalt extraction in DRC is associated with several human rights challenges, including poor and dangerous working conditions, health implications due to pollution, child labour as well as conflicts between artisanal and industrial miners and environmental degradation (Sovacool, 2019).

Artisanal and small-scale mining

Artisanal mining means mining by hand or by basic tools. Artisanal or small-scale mining has become a major part of the local economy with more than two million Congolese relying on it for their income who in turn support a further 10 million people (World Economic Forum, 2020) making it the second largest employment sector in DRC(Banza Lubaba Nkulu et al, 2018). The amount of cobalt produced by artisanal and small-scale miners in DRC is estimated to be somewhere between 15 to 30 percent of the total production (World Economic Forum, 2020). In a country where poverty is rife and employment opportunities scarce, mining has become an important source of income for many. While the work is dangerous and can cause serious health problems, it can also provide higher income than many other types of employment. Income varies, but typically reaches 30 to 50 dollars a month (Sovacool, 2019).

Finland is the second largest refiner of cobalt in the world, right after China (van den Brink, Kleijn, Sprecher, & Tukker, 2020). Cobalt extracted by artisanal miners frequently gets mixed with industrially mined material making it all but impossible to trace the source of cobalt used in the end products (Baumann-Pauly & Cremerlyi, 2020). This means that it is very likely that some of the cobalt brought to Finland for refining has been extracted in questionable conditions. Since DRC produces most of the cobalt required for battery technology, which we all rely on, we are all responsible for finding ways to solve the challenges associated with cobalt extraction.

Key negative impacts of mining in DRC

Artisanal miners operate in appalling conditions. Tools used are crude, protective gear is non-existent and mineshafts are unstable, work is physically demanding, workdays are long and child labour is rife (Sovacool, 2019). High levels of cobalt have been linked to for example lung disease and heart failure and miners have been found to be prone to silicosis and tuberculosis (Watts, 2019).

The mining region of DRC is considered one of the most polluted regions in the world, mainly due to metal mining (Van Brusselen, Kayembe-Kitenge, Mbuyi-Musanzayi, Lubala Kasole, Kabamba Ngombe, Musa Obadia, Kyanika wa Mukoma, Van Herck, Avonts, Devriendt, Smolders, Banza Lubaba Nkulu, & Nemery, 2020). Environmental impacts include biodiversity loss and destruction of natural habitat, deforestation, soil erosion, air pollution, siltation of wetlands, changes in river ecology and land instability (Sovacool, 2019). Environmental degradation has a direct effect on the health of people and for example children in mining areas have been found to be heavily contaminated by cobalt (Banza Lubaba Nkulu et al, 2018).

Artisanal miners are at risk of exploitation by their bosses and the companies they sell the cobalt to and mining companies can also artificially depress prices (Sovacool, 2019). The negotiation power of artisanal miners is weak. There is no nationally representative union, social movements for mining rights are scarce and when opposition occurs, it is often local and suppressed fast (Sovacool, 2019). Another problem is the volatility of cobalt price, it can vary dramatically which directly affects the income of miners and the number of people engaged in artisanal mining.

In the case of DRC, the term resource curse is sometimes used. Despite immense natural resources, or because of it, the country has a long history of poverty, corruption, weak state, conflict, exploitation, and colonialism. The strong reliance on mining alone means that other economic sectors are underdeveloped, and corruption and poor governance means investment in infrastructure, education and healthcare is low (Sovacool, 2019).

Responsibly sourced cobalt

Despite its many problems, artisanal mining is an extremely important source of income for many in DRC. In a country where 80 percent of the population is estimated to be either unemployed or underemployed, artisanal mining provides much needed income (World Economic Forum, 2020). Banning the use of cobalt extracted by artisanal miners would thus be detrimental to the livelihood of a large number of Congolese. It would also be very impractical as with the increasing demand for cobalt, production outside DRC will not be able to meet this demand. However, action should be taken to improve the lot of these artisanal miners.

Common standards

The increased awareness of human rights violations associated with cobalt extracted in DRC has led some companies to source their cobalt elsewhere (Baumann-Pauly, 2020). However, due to the importance of cobalt as a source of income for Congolese, rather than excluding cobalt extracted by artisanal mining from the supply chain a common standard should be created (Baumann-Pauly, 2020). This industry wide standard for mine safety and child labour would define responsible artisanal mining and improve the confidence of both consumers and the industry that when sourcing cobalt from DRC, they are not contributing to human rights violations (Baumann-Pauly, 2020).

Formalizing artisanal mining

Formalization processes of artisanal and small-scale farming have been experimented in some mining sites to regulate mining methods and working conditions (Baumann-Pauly, 2020). Typically, a formalization process involves setting up a cooperative, which miners must join, fencing off mining areas with access control and introducing safety measures (World Economic Forum, 2020). In some cases, the cooperatives work closely with a mining company that may prepare open pits for artisanal miners and hold exclusive rights to purchasing the supply (World Economic Forum, 2020). This arrangement has however raised critique. Corporate-led formalization processes can be seen as a way for companies to shift the risk of price fluctuation and reputational risk from corporations to artisanal miners (Calvão, Mcdonald, & Bolay, 2021). The formalization process may thus benefit mining companies rather than artisanal miners.

Other employment opportunities

Despite its economic importance, it seems unlikely that artisanal mining will improve the quality of life of people in the long run (Perks, 2011). Artisanal mining, as well as child labour, is poverty driven (Perks, 2011) and lack of other employment opportunities drive people to artisanal mining. Therefore, all measures that alleviate poverty will reduce the number of people engaged in artisanal mining and reduce the negative impacts. Due to the heavy dependence on mining in DRC, other economic sectors have been neglected (Perks, 2011) and thus offer few employment opportunities. Investing in economic diversification and providing other employment opportunities, such as farming, manufacturing, and commerce, could greatly benefit the local people and reduce their reliance on artisanal mining for income.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

In DRC, mining is closely connected to many of the sustainable development goals set by the United Nations. Most pressing are perhaps the SDG number 1 ‘No poverty’ and SDG number 8 ‘Decent work and economic growth’. However, the pursuit of economic improvements can have, and has had, detrimental consequences on the environment thus the need for environmental regulation should not be forgotten either. Despite its vast natural resources, the majority of Congolese live in poverty, are unemployed or underemployed and many, even children, work in appalling conditions in artisanal mines. Due to the central role of mining in the economy of DRC and as an employer, addressing the challenges associated with the mining sector are a key in leading the country out of poverty as well as creating decent employment opportunities and securing decent income for the people of DRC.

Conclusion

The cobalt in our mobile phones, laptops and electric vehicles come at a high human cost to the artisanal miners in DRC. It is the responsibility of us all to ensure a living wage and decent working condition to the people making our digital leap and carbon neutral future possible. However, the task is not easy as the challenges associated with mineral extraction in DRC are complicated, wicked problems for which no simple solution exists. Formalization and standardisation processes are only the first step to improve the working conditions of artisanal miners, however, as it is unlikely to yield long-term economic benefits, more comprehensive measures are required to truly achieve a change. These measures would include stronger government institutions and negotiation power, eradication of corruption, diversification of the economy and investment in infrastructure, healthcare and education making it possible for people to make a living outside the mining sector.

References

Banza Lubaba Nkulu, C., Casas, L, Haufroid, V., De Putter, T., Saenen, N.D., Kayembe-Kitenge, T., Musa Obadia, P., Kyanika Wa Mukoma, D., Lunda Ilunga, J.-M., Nawrot, T.S., Luboya Numbi, O., Smolders, E., & Nemery, B. (2018). Sustainability of Artisanal Mining of Cobalt in DR Congo. Nature sustainability 1(9), 495–504

van den Brink, S., Kleijn, R., Sprecher, B., & Tukker, A. (2020). Identifying supply risks by mapping the cobalt supply chain. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 156

Van Brusselen, D., Kayembe-Kitenge, T., Mbuyi-Musanzayi, S., Lubala Kasole, T., Kabamba Ngombe, L., Musa Obadia, P., Kyanika wa Mukoma, D., Van Herck, K., Avonts, D., Devriendt, K., Smolders, E., Banza Lubaba Nkulu, C., & Nemery, B. (2020). Metal Mining and Birth Defects: a Case-Control Study in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lancet Planet health 4(4), e158–e167

Baumann-Pauly, D. (2020). Why Cobalt Mining in the DRC Needs Urgent Attention. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/blog/why-cobalt-mining-drc-needs-urgent-attention

Baumann-Pauly, D. & Cremerlyi, S. (2020). As cobalt demand booms, companies must do more to protect Congolese miners. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/as-cobalt-demand-booms-companies-must-do-more-to-protect-congolese-miners-149486

Calvão, F., Mcdonald, C.E.A., & Bolay, M. (2021). Cobalt Mining and the Corporate Outsourcing of Responsibility in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The extractive industries and society, n. pag.

Perks, R. (2011). ‘Can I go?’—Exiting the artisanal mining sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo Journal of International Development J. Int. Dev. 23, 1115–1127

Sovacool, B.K. (2019). The Precarious Political Economy of Cobalt: Balancing Prosperity, Poverty, and Brutality in Artisanal and Industrial Mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The extractive industries and society 6(3), 915–939

Statista (2021). Democratic Republic of Congo: Estimated Total Population from 2016 to 2026. Retrieved fromhttps://www.statista.com/statistics/1041527/total-population-of-democratic-republic-of-the-congo/

U.S. Geological Survey (2021). Cobalt Statistics and Information. Retrieved fromhttps://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021-cobalt.pdf

Watts, J. (2019). How the race for cobalt risks turning it from miracle metal to deadly chemical. The Guardian. Retrieved fromhttps://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/dec/18/how-the-race-for-cobalt-risks-turning-it-from-miracle-metal-to-deadly-chemical

The World Bank (2021). The World Bank in DRC. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview

World Economic Forum (2020). Making Mining Safe and Fair: Artisanal cobalt extraction in the Democratic Republic of Congo. World Economic Forum White Paper September 2020. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/making-mining-safe-and-fair-artisanal-cobalt-extraction-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo

Cobalt Refining Industry in Finland

Text by Santeri Mikkola

Democratic Republic of Congo is the world’s leading producer of raw cobalt – according to U.S. Geological Survey (2021) approximately 70 percent of the world’s cobalt is extracted in the DRC. After China, Finland is the second largest refiner of cobalt in the world (Statista, 2020). In 2018, Finland’s global market share was roughly 15 percent (Lindström & Rigatelli, 2021). Despite the small-scale cobalt extracting in Finland (as a by-product of other minerals), the refining industry relies heavily on imported cobalt.

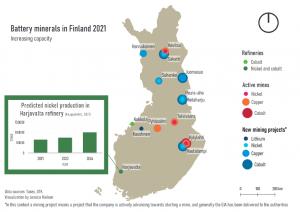

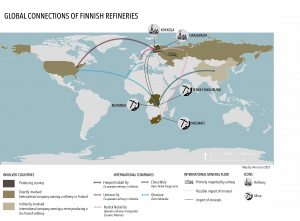

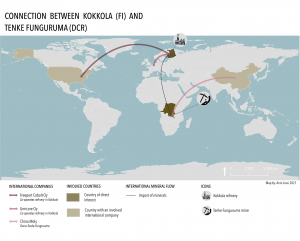

The cobalt refining industry in Finland is concentrated into two industrial parks: Kokkola Industrial Park and Harjavalta Industrial Park (see map above). In Harjavalta, the production is run by a Russian-based company Norilsk Nickel. According to Nornickel representatives, the cobalt refined in Harjavalta is imported primarily from Russia by rail (Gerden, 2020; Jurvelin, 2021; Nornickel, 2021b). Nornickel does also have connections to Africa: it owns 50 percent of South-African nickel mine called Nkomati (Nornickel, 2021a). However, the import destinations of the minerals extracted in Nkomati remain slightly obscure. In April 2021, Nornickel announced that it would increase its production capacity in Harjavalta in the coming years (Nornickel Harjavalta, 2021). Nevertheless, Nornickel’s main product is nickel, not cobalt. If we look solely at cobalt, the largest volume of refining in Finland occurs in Kokkola.

Kokkola Industrial Park has two transnational corporations, who are running the cobalt refining business (see map below). They are the Belgian-based Umicore Oy and American-based Freeport Cobalt Oy (a subsidiary of Freeport-McMoRan). Both companies import cobalt from the DRC. Freeport Cobalt Oy imports from Tenke Fungurume mine, which it previously owned, but sold to China Moly in 2017 (Reuters, 2017). In December 2020, Freeport Cobalt announced that it was granted a recognition by Responsible Minerals Initiatives (RMI), which validates that its cobalt is responsibly sourced (Freeport Cobalt Oy, 2020).

Umicore cobalt sourcing is more diversified than Freeport Cobalt. In their website, Umicore underlines that their cobalt is exempted from artisanally and small-scale mined materials (ASM), and that in 2018, 75 percent of the cobalt used in Umicore’s refineries are received from ”large-scale mining (LSM) activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo” (Umicore Oy, 2021). However, the section of ”Origin of cobalt raw materials” includes only a few short sentences, and leaves questions hanging in the air. For example, where does the last quarter of cobalt come from? In May 2019, Umicore and Glencore (an Anglo-Swiss multinational mining company) entered into a long-term agreement on supply of cobalt from Glencore’s mines KCC and Mutanda, which are located in the DRC (Cooke, 2021; Glencore, 2019). Glencore’s mining practices have been widely accused of exploitation of child labour, human rights issues and environmental destruction (Kelly, 2019).

So the key question is whether the cobalt industry in Finland has any negative spillovers in the Democratic Republic of Congo? Most likely the answer is yes. It’s not solely a problem caused by the multinational companies working in Finland, but it’s rather a larger systematic problem. Because of the complicated and multi-staged supply and production chains, it’s almost impossible to fully trace the origin of the cobalt and ensure its accountability. The World Economic Forum estimated in their report (2020), that 15-30 percent of the cobalt extracted in the DRC is artisanally mined. Artisanally mined cobalt is linked to serious human right risks and violations. Large-scale mining (or ”industrial mining”) products are frequently mixed with artisanally mined cobalt (Baumann-Pauly & Cremerlyi, 2020), and it is therefore very likely that cobalt imported into Finland is also partly artisanally mined. It’s also noteworthy that the companies mentioned above are eagerly proclaiming the sustainability of their production and responsibility, but at the same time they’re very vague on their cobalt sources. This can also just strengthen the hypothesis that even the refineries are not entirely sure where their cobalt comes from.

References

Cooke, P. (2021). The lithium wars: From kokkola to the congo for the 500 mile battery.Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 13(4215), 4215. doi:10.3390/su13084215

Freeport Cobalt Oy. (2020). Conformant letter. Retrieved from https://www.freeportcobalt.com/assets/fc/pdf/ConformantLetter.pdf

Gerden, E. (2020, Russia ready to increase domestic cobalt production – even under the pacific ocean. Retrieved from https://resourceworld.com/russia-ready-to-increase-domestic-cobalt-production-even-under-the-pacific-ocean/

Glencore. (2019). Umicore and glencore develop partnership for sustainable cobalt supply in battery materials. Retrieved from https://www.glencore.com/media-and-insights/news/umicore-and-glencore-develop-partnership-for-sustainable-cobalt-supply-in-battery-materials

Jurvelin, K. (2021, ). Nornickeliltä suurinvestointi: Harjavallan nikkelikapasiteetti liki kaksinkertaistetaan – euroopan akkumarkkinoilla on nyt hirmuinen nikkelin himo.KauppalehtiRetrieved from https://www.kauppalehti.fi/uutiset/nornickelilta-suurinvestointi-harjavallan-nikkelikapasiteetti-liki-kaksinkertaistetaan-euroopan-akkumarkkinoilla-on-nyt-hirmuinen-nikkelin-himo/9d001180-b87f-41ac-adae-c5a3b4b86f1f

Kelly, A. (2019, ). Apple and google named in US lawsuit over congolese child cobalt mining deaths.The GuardianRetrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/dec/16/apple-and-google-named-in-us-lawsuit-over-congolese-child-cobalt-mining-deaths

Lindström, L., & Rigatelli, S. (2021, ). Pimeä akku.YleRetrieved from https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11748022

Nornickel. (2021a). Company profile. Retrieved from https://www.nornickel.com/company/profile/

Nornickel. (2021b). Nornickel – finland. Retrieved from https://www.nornickel.com/business/assets/finland/

Nornickel Harjavalta. (2021). Nornickel harjavalta vastaa sähköautojen akkumetallien kasvavaan kysyntään – tuotanto lähes kaksinkertaistuu. Retrieved from https://www.nornickel.fi/b/nornickel-harjavalta-vastaa-sahkoautojen-akkumetallien-kasvavaan-kysyntaan–tuotanto-lahes-kaksinkertaistuu

Reuters. (2017, ). Freeport, china moly agree to end talks on cobalt assets.ReutersRetrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-freeport-mcmoran-cmoc-idUSKBN1952V5

Statista. (2020). Leading countries based on annual cobalt refinery capacity as of 2017 (in metric tons)*. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/339798/annual-cobalt-refinery-capacity-by-country/

U.S. Geological Survey. (2021). Cobalt.().USGS. Retrieved from https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021-cobalt.pdf

Umicore Oy. (2021). Origin of cobalt raw materials . Retrieved from https://www.umicore.com/en/about/sustainability/origin-of-cobalt-raw-materials

World Economic Forum. (2020). Making mining safe

and fair: Artisanal cobalt extraction in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Making_Mining_Safe_2020.pdf.

Positive links to the SDGs in Tenke Fungurume & Kokkola refinery cases

Text by Hanna Kuivalainen

Like Koivula has very well opened, mining can never be fully sustainable in all three dimensions of being ecologically, socially and economically sustainable. At least one, often all areas, are somehow compromised. Still, many positive spillover effects can be linked to the mining industry especially when looking at the employment effect, which often contributes in terms of well-being to the whole community.

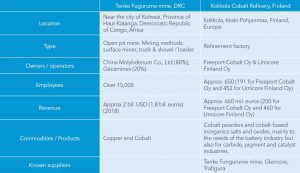

In this text we will take a closer look at the positive spillovers of Kokkola Cobalt Refinery in Finland and Tenke Fungurume Mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo (see map above and table 1 below). These two example cases are selected for the review because the spillover effects of the mining industry are diverse and appear differently in different societal contexts. Kokkola Refinery, therefore, represents a responsible Western actor with strong control of local government and authorities under strict legislation. Tenke Fungurume Mine on the other hand represents a mine in a developing country where stability and inequality of society often challenges the sustainability of acting. In developing countries, where there is no reliable government and enforcement, mining appears to have more far-reaching negative than positive spillover effects on the society. When researching, especially the positive spillovers of mining, we must remember to be extremely critical since the findings are often presented by the mining actors themselves. Therefore, the results might be manipulated to justify the action.

Table 1: Key facts about Tenke Fungurume Mine and Kokkola Cobalt Refinery.

Table 2: Positive links to the SDGs.

Kokkola Cobalt Refinery

One of the biggest Cobalt refineries in the world, share of global cobalt market about 15% (Sajari 2017)

Employment opportunities outside of national growth centres, economic growth & tax revenues

The cobalt refinery employs approximately 650 people in total, making it a major employer in Kokkola, a Finnish provincial city of a bit less than 50 000 inhabitants. The refinery is contributing to the inhabitants’ well-being through creating important employment opportunities. The number of employees in the activities run by Umicore Finland Oy has been steadily growing from 415 people in 2016 to 452 in 2019. The latest numbers including i.e. the effects of the covid-19 pandemic to the annual turnover or number of employees are not yet openly available. (Finder 2019, Hakala 2020)

Following the global trend of increasing urbanization, Finland is projected to have only three growing urban centres by 2040. (MDI 2019) The refinery provides much needed employment to the shrinking provincial centres, of which Kokkola is one.

Refinement activity is considered a part of the secondary sector of the economy, referred to also as the manufacturing or production sector. The secondary sector has traditionally formed a substantial part of the GDP of developed countries and fostered industrialization. Manufacturing industry takes the outputs (raw materials) of the primary sector (such as mining) and uses them to produce a higher value added product, making the sector an important engine of economic growth. Countries exporting manufactured products usually generate higher GDP growth (compared to countries exporting raw materials) which supports higher incomes and tax revenues needed to fund quality-of-life initiatives such as health care and infrastructure. The field is also an important source for engineering jobs. (Gyathri 2016)

Learning opportunities and engaging the youth

The refinery collaborates with the universities, polytechnics and vocational schools of the region in order to raise the industry’s visibility among the youth and promote the different employment opportunities offered. The refinery facilitates many different ways to secure a job, such as internships, apprenticeships and on-the-job training periods. Work tasks are rotated where possible to ensure continuous learning and better job satisfaction. (Hakala 2020)

Keeping up with the requirements of a healthy and just working environment

The refinement activities generate cobalt dust, which is a health hazard and potentially carcinogenic. Protection from the dust is provided through motorized and non-motorized masks of the highest protection class P3. In the future, the more expensive motorized masks will be made available for all employees. Dust levels are continuously measured from the air of the production facilities.

Workspaces tend to be also hot and noisy. Noise is controlled with earmuffs. In the past, the temperature in the production hall could rise to more than forty degrees celsius, but thanks to a new ventilation system the hall now cools down more efficiently.

Eye showers are available throughout the production facility in case of accidental contact of the eye with cobalt chemicals. Workers must wear goggles, a helmet and any other protective equipment where deemed necessary.

The health of the refinery employees is monitored, and workers’ urine is screened to measure cobalt levels.

Labor rights are promoted through i.e. the existence of labor unions as well as workplace stewards, in accordance with the requirements of the Finnish law. (Hakala 2020)

Promoting sustainable production

From the Freeport Cobalt Oy website:

“We are the first cobalt chemical company to achieve Conformant Cobalt Downstream Facility status through the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI)’s Downstream Assessment Program (DAP). The RMI developed the Downstream Assessment Program to assess downstream companies within the cobalt or tin, tantalum, tungsten and old (3TGs) supply chains. It uses third-party auditors to independently assess and verify that companies have systems in place to responsibly source minerals in alignment with OECD Guidelines for Responsible Supply Chain of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas.”

The corporate policies of Freeport Cobalt include sustainability policies and programs, including (but not limited to) Safety and Health, Environmental, Social Performance, and Responsible Sourcing of Minerals. (Freeport Cobalt 2021)

Tenke Fungurume Mine

Largest copper producer in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and one of the largest cobalt reserves in the world (Mining Data Online 2020)

Employment for the local vulnerable population & economic growth and tax revenues for the developing nation

In 2017, the mining sector accounted for 17,40% of DRC’s GDP, 55,16% of total government revenues, 99,3% of total exports and a quarter of total employment (EITI 2021). DRC’s economic growth is mainly driven by the mining industry, which is led by a robust demand from China. The country’s economic growth decelerated from its pre-COVID level of 4.4% in 2019, to an estimated 0.8% in 2020. (The World Bank 2021)

DRC has the third largest population of poor globally (The World Bank 2021). The mining sector represents an important income opportunity for that vulnerable part of the population.

The Tenke Fungurume mine employs more than 15,000 workers. In addition, there are about 110,000 regular artisanal miners in the Katanga region, rising to about 150,000 on a seasonal basis. (Amnesty International 2019)

Promoting workers’ rights and decent compensation

The Tenke Fungurume mine’s large number of employees gives the workers more momentum and makes it harder for the company to just dismiss their claims.

In may 2020 the mine’s workers had a strike that ended in a compromise agreement with the management over compensation for working in isolation for two months due to COVID-19. The agreement addressed the issues of the ‘isolation bonus’, working hours and the conditions under which workers can rotate. (Reuters 2020)

Community projects by mining companies in the lack of state intervention

The Democratic Republic of Congo can be described as a failed state, where the government has been unable to fulfill its responsibility of providing its citizens security and access to basic services, partly due to the combination of decades of civil war and armed violence together with wide-spread corruption (Titeca & De Herdt 2011). Where the state is not capable of taking care of its citizens, private companies have the possibility to step up and take part of the task.

Mining companies should comply with the recently iterated Congolese mining law that requires mining companies to contribute a set percentage of their revenue directly to local development. (International Crisis Group 2020)

Indeed, mining companies have had some development projects in Congo recently: Umicore, for example, has built a school, and Glencore has run summer camps. Companies support agricultural projects to find alternative sources of income to mining. (Yle 2021)

References

Amnesty International (2019, July 1). DRC: Withdraw armed forces from Fungurume mines to avert bloodshed. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/07/democratic-republic-of-congo-fungurume-mines/

EITI: Democratic Republic of Congo, overview (2021). https://eiti.org/democratic-republic-of-congo

International Crisis Group (2020, June 30). Report n. 290. Mineral Concessions: Avoiding Conflict in DR Congo’s Mining Heartland. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/democratic-republic-congo/290-mineral-concessions-avoiding-conflict-dr-congos-mining-heartland

Lindström, L. & Rigatelli, S. (2021, March 14). Pimeä akku. Yle. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11748022

Mining Data Online: Tenke Fungurume (2020). https://miningdataonline.com/property/302/Tenke-Fungurume-Mine.aspx

Reuters (2020, May 24). UPDATE 2-Workers at China Moly’s Congo mine end one-day strike over COVID-19. https://www.reuters.com/article/congo-mining-cmoc-idUSL8N2D6071

Titeca, K., & De Herdt, T. (2011). Real governance beyond the ‘failed state’: Negotiating education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. African Affairs, 110(439), 213-231.

The World Bank: Democratic Republic of Congo, overview (2021). https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview

Finder: Umicore Finland Oy (2019). https://www.finder.fi/Teollisuuskemikaalit/Umicore+Finland+Oy/Kokkola/yhteystiedot/2853400

Freeport Cobalt: Sustainability (2021). https://www.freeportcobalt.com/about/sustainability.html

Gayathri, R. (2016). Role and Importance of Secondary Sector. University of Mysore. https://uni-mysore.ac.in/sites/default/files/content/news_letter15.pdf

Hakala, J. (2020, September 23). REPORTAASI: Koboltin jalostus työllistää Kokkolassa. Tekijälehti. https://tekijalehti.fi/2020/09/23/reportaasi-koboltin-jalostus-tyollistaa-kokkolassa/

Lindström, L. & Rigatelli, S. (2021, March 14). Pimeä akku. Yle. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11748022

MDI: Väestöennuste 2040 (2019, May 16). https://www.mdi.fi/ennuste2040/

Sajari, P. (2017, December 17). Kokkolassa on maailman suurin koboltin jalostamo – sieltä metallia myydään muun muassa Applen laitteisiin. Helsingin Sanomat. https://www.hs.fi/talous/art-2000005493173.html

Finder: Umicore Finland Oy (2019). https://www.finder.fi/Teollisuuskemikaalit/Umicore+Finland+Oy/Kokkola/yhteystiedot/2853400

Hakala, J. (2020, September 23). REPORTAASI: Koboltin jalostus työllistää Kokkolassa. Tekijälehti. https://tekijalehti.fi/2020/09/23/reportaasi-koboltin-jalostus-tyollistaa-kokkolassa/

Lindström, L. & Rigatelli, S. (2021, March 14). Pimeä akku. Yle. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11748022

Mining Data Online: Tenke Fungurume (2019). https://miningdataonline.com/property/302/Tenke-Fungurume-Mine.aspx#Costs

United Nations: Sustainable Development Goals (2020). https://sdgs.un.org/goals