Elli Pölhö, Katja Sula, Ida Volotin ja Anne Yli-Karhu

Our teaching experiment is part of the course Opettaja työnsä tutkijana (teacher as a Researcher) which is one of the master’s degree studies. The starting point of the course was to develop and thereby develop our own research approach and increase our digital pedagogical competence (OTT, 2022). In this course, we had to plan, implement and further develop a lesson which was implemented for three different home economics study groups. The second and third teaching groups received a more developed version of the lesson.

Starting points and backgrounds of the teaching experiment

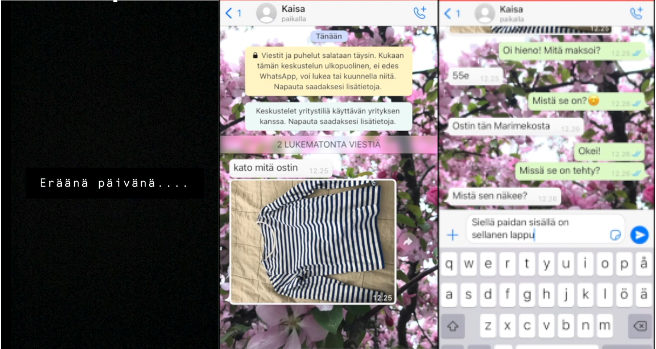

The main theme in our teaching experiment was to teach in another way – we also had to consider hands-on approach and interactivity home economics distance teaching. As we were focusing on hands-on approach, we wanted to look for variation and diversity in work methods and to bring out different ways of learning. Through hands-on approach, we also wanted to increase the interaction between students, because in distance education the interaction between teacher and student is often incomplete (Rantanen & Palojoki, 2015, p. 85.) As distance teachers we strive to be encouraging and activate students despite the distance. In addition to our own goals, the goal of the teaching experiment was to guide pupils to evaluate their own consumption behavior and the development of responsibility for clothing-related choices. Responsibility, both as a value and a goal, is considered important in home economics and is also considered a basic goal of education (POPS, 2014; Wennonen & Palojoki, 2015, p. 18).

Description of the teaching experiment

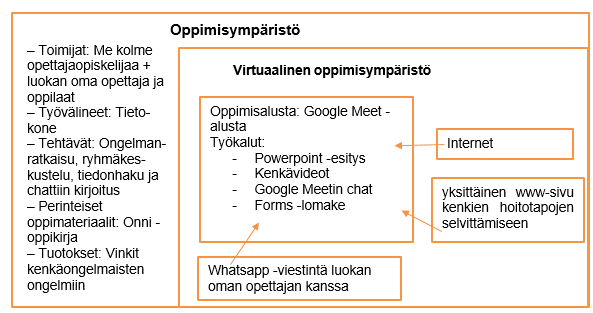

Our pupils were on the 7th grade. The teaching experiment consisted of three lessons which were each 1 x 60 minutes long. The actual distance learning took place as follows: We teachers taught everyone from home and the students were at school with their own teacher. The learning environments consisted of the classroom and e-learning environments. We held the same lesson for three different classes and developed our teaching even better after each lesson.

Our teaching experiment was built on learning approaches such as behaviorism and constructivism. In the lessons, we aimed for an interactive and hands-on distance learning environment through a variety of tasks. In our teaching, we utilized the technological applications Mentimeter and Flinga.

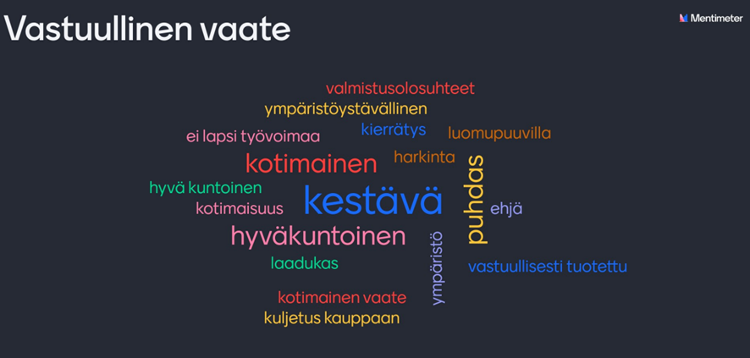

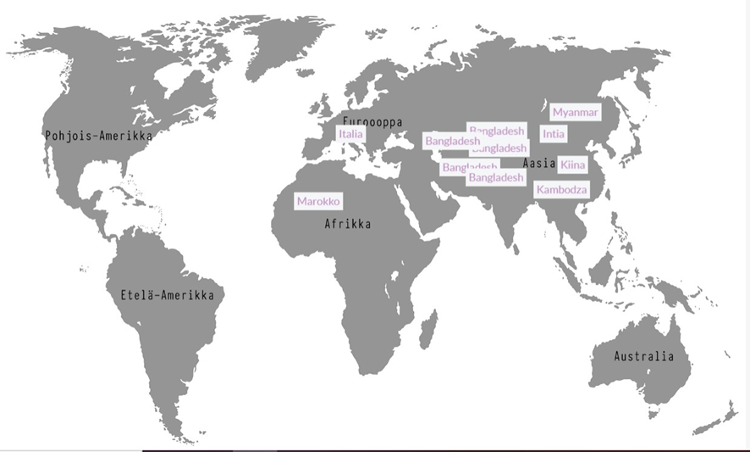

The purpose was to awaken pupils to our actual subject. In the mentimeter, pupils had to think about what they think of the word “responsible clothing”. They were allowed to share their thoughts on responsible clothing anonymously. Flinga was utilized as a stimulus for discussion about the clothing industry. In this way, we were able to get information about the pupils’ current information as well as look at the countries where their own clothes were made. Both tasks sparked a lot of discussion in the groups, and we got some great insights.

In the pair task, pupils memorized sentences they dictated to each other. The sentences dealt with responsible clothing and were in the kitchens. Students searched the sentences in pairs from the kitchens. The purpose of this section was to add interactivity among the students and functionality in the lesson. As students try to memorize relatively challenging and new topics, they must focus on the movement to tune the brain in a different way than when it done statically. This also increases focus, as the thing to remember is the whole sentence. In addition, this section supports the objectives recorded in the curriculum (POPS, 2014).

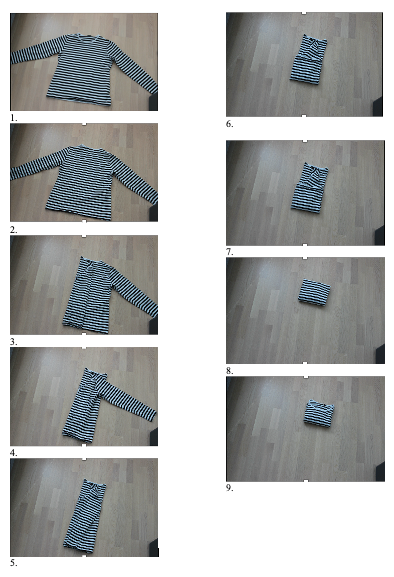

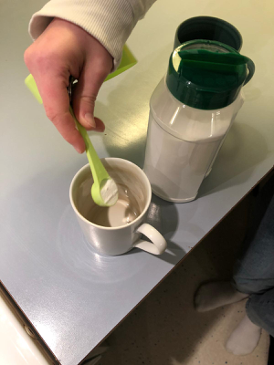

The other hands-on task was interactive group task. In the task, pupils consider together the final disposal of different textiles (torn and dirty). Before that we showed video made by us which dealt with extending the life cycle of clothing. Overall, the lessons were a great success, except for a few remarks we made during the reflection. We believe lessons were succeeded since we had prepared for the lessons by carefully planning and practicing. The lessons were very interesting to implement, and they concretized the whole development tasks well.

References

OTT. (2022). Opettaja työnsä tutkijana. Helsingin yliopisto.

POPS. (2014). Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2014. Opetushallituksen verkkosivut. Saatavilla: www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf#page=437&zoom=100,0,0

Rantanen, M. & Palojoki, P. (2015). Kotitalous verkko-opetuksena. Teoksessa H, Janhonen-Abruquah & P, Palojoki (toim.), Luova ja vastuullinen kotitalousopetus. Creative and responsible home economics education (s. 73–94). Kotitalous- ja käsityötieteiden julkaisuja 38. Helsingin yliopisto. Helsinki: Unigrafia.

Wennonen, S. & Palojoki, P. (2015). Vastuullisuus ja vastuullisuuskasvatus kotitalousopetuksessa. Teoksessa H, Janhonen-Abruquah & P, Palojoki (toim.), Luova ja vastuullinen kotitalousopetus. Creative and responsible home economics education (s. 6–28). Kotitalous- ja käsityötieteiden julkaisuja 38. Helsingin yliopisto. Helsinki: Unigrafia.