What were the technical and other hurdles in the digitisation project of the old Royal Academy of Turku dissertations? And how were they solved?

By Juha Hakala, Senior adviser, the National Library of Finland

Digitising for perpetuity and maximum accessibility

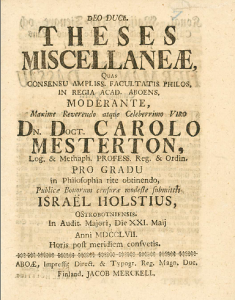

Royal Academy of Turku was the first university in Finland. It was established in Turku in 1640. In 1809 Finland became part of Russian empire and the university became The Imperial Alexander University of Finland. After the Great Fire of Turku in 1827 the university was relocated in Helsinki, where it was renamed once more after Finland became independent; since 1919 the name of the institution has been University of Helsinki.

Any project digitising old and valuable collections should design the process in such a way that it will never be necessary to digitise the documents again. But the digitised collection should also be widely available – unless there are legal or other constraints preventing open access. Therefore the digitised documents must be submitted both to a digital asset management system available to the public, and to secure digital archive. And users should be able to find all these materials and tell them apart, which means that some cataloguing enhancements must be made.

With private funding the National Library of Finland has digitised all the 4609 Royal Academy dissertations in its collections. Both the documents themselves and all related metadata will be made available under CC0 license when the project is completed in autumn 2015. Therefore digitisation will help the library to preserve the original documents, and at the same time improve access to the information. This article presents the technical and other hurdles this project – called TAV for short – faced, and solutions that were found.

The collection

Royal Academy of Turku dissertations form an important part of the historical national collection. The National Library’s collection is the most complete one in Finland, and with few exceptions the titles missing have vanished completely (they may have existed only as manuscripts). However, in order to create as complete a collection as possible, the library has in the past microfilmed publications missing from the collection. TAV continued this tradition by digitising books from other libraries’ collections when these items held content – dedications etc. – missing from the item(s) held by the National Library. This process would not have been possible without prior knowledge of Royal Academy of Turku collections in other libraries.

The most significant programmatic change was the addition of rights metadata.

Since the National Library’s collection often contains two or even more items of dissertations, digitisation process began by analysis of the collection in order to select the item(s) to be digitised. If all items were more or less identical, the best preserved one was digitised. But if there were differences in the intellectual content, all dissimilar items were selected.

Each printed and digitised item was treated as an independent manifestation of the work and catalogued separately. Bibliographic records were enriched so that if several items were processed, the differences between them became apparent. But other improvements were required as well. Some of these were made manually, some programmatically. Changes of the former kind concentrated on authority control. For instance, the roles of authors and other agents are now included:

700 1# $a Dahlsteen, Andreas, $d n. 1715-1771, $e piirtäjä.

700 1# $a Mennander, Carl Fredrik, $d 1712-1786, $e preeses.

700 1# $a Seeliger, Johan Henrik, $d 1704-1763, $e kaivertaja.

710 0# $a Kämpe, Johan (kirjapaino, Turku, 1729-1753)

Cataloguing language is Finnish, so for a foreign user it may be difficult to see that in this example Johan Seeliger is the engraver, and the book was printed in Johan Kämpe’s printing house. 700 and 710 subfield $e is repeatable, but at least for now we use just Finnish. If and when the policy changes, it is easy to add these terms in e.g. Swedish and English programmatically.

The most significant programmatic change was the addition of rights metadata. Traditionally national bibliographic records have provided the Web addresses of catalogued resources, but no information about license has been provided. This is a problem, since a user can retrieve an electronic resource without having any idea of how the document can be used. The project added rights metadata like this to the records in order eliminate the problem:

506 0# $a Aineisto on vapaasti saatavissa; $f Unrestricted online access $2 star

540 ## $c Public domain $u https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.fi

Any resource free of copyright and digitised by the library could in principle get similar 506 and 540 tags. No details are included in the metadata record; only a link to the Finnish summary of the Creative commons Public Domain dedication is provided. The cataloguing experts group in Finland has recently decided that this approach should be used with all well-known licenses such as CC0 1.0 or CC BY 4.0.

In this instance MARC 21 provides poor multilingual support. In 506 only two languages can be used, and another one must be English. Moreover, the term list provided by STAR vocabulary is rather short. 540 $a-$d are non-repeatable, so if no generic term such as “public domain” can be used, there is a problem. 540 $u can be repeated, so it is possible to provide links to the CC Public Domain dedications in multiple languages. So far, only a link to the Finnish version is given, but from that page users can find links to the text in other languages.

MARC 21 conversion programmes were designed in close co-operation between the collection specialist / cataloguer hired by the project and a programmer in the library’s network services department.

Digitisation

The National Library did not need to purchase any additional software or hardware to digitise the dissertations in house or to make them available to the public. The Library’s Centre for Preservation and Digitisation has used docWORKS and Finereader for several years, and the TAV project did not have any requirements these applications would not have been able to meet, with one exception: FineReader module for Latin grammar was purchased in order to improve the OCR results.

The first step of the digitisation process was harvesting of the enriched MARC 21 records to the docWORKS application which manages the digitisation process. Such management means that all metadata needed for e.g. long term preservation of digitised resources must be created. Administrative metadata plays a vital role in this, and a large amount of it is created. For instance, all scanner settings are stored as technical metadata to images, and if images are modified by e.g. cropping them, all changes are stored as preservation metadata. As regards descriptive metadata, new bibliographic records, based on those of printed dissertations, were programmatically created to the digital surrogates. These MARC 21 records and those describing printed manifestations of dissertations are interlinked in library’s bibliographic databases.

“The benefits of digitising resources in-house are considerable.”

The benefits of digitising resources in-house are considerable. From the point of view of the project manager the main thing is that the project had full control of literally every aspect of the digitisation process. This is vitally important, not least because digital preservation is a process which begins when the documents are created. If there are mistakes made early on, it may be impossible to fix the problems later. For instance, if check sums are not calculated immediately after the files have been created, it is not possible to check if the files have been changed inadvertently (or maliciously). Or, if the technical details about the scanning process are not preserved in technical metadata, it may be difficult or even impossible to reproduce the images correctly later.

In most respects the digitisation process was typical for old printed materials. The exception was the cases when two or more items of a dissertation were digitised. Initially digital hybrids were created, combining content from two or more printed original documents. But we decided to abandon this approach to maintain 1:1 relationship between printed originals and digital surrogates. This approach is also eminently suitable for future FRBRization and most likely also easier to understand for the users.

The end product of the digitisation process is a METS container containing rich descriptive and administrative metadata about the resource, and the digital resource itself in various formats: uncompressed TIFF and compressed JPEG page images for archival and public use, and METS/ALTO encoded full text with “lightweight” page encoding. These containers are used for exchange of metadata and documents between the National Library’s productions systems.

Access

The National Library has DSpace-based digital asset management system, Doria, which has been in production for eight years. Approximately half of the dissertations have been available in Doria as the Dissertations of the Royal Academy of Turku -collection since 2011.

The test load of the dissertations digitised in the second part of the project in 2014 was done in May – June 2015. Production load will be done when problems revealed by the test have been fixed.

Doria load processes begin by migration of metadata from MARCXML used in docWORKS to Dublin Core supported by DSpace. In order to capture all relevant metadata, the project developed its own DC application profile. This can be done because DSpace allows tuning of indexing and user interface at the collection level.

“The biggest change is that the library intends to make the entire collection available as open data.”

The National Library has cooperated with researchers in all stages of the project in order to guarantee that the search capabilities and user interface design meet the requirements. The GUI designed in the first phase of the project has served the users well, but has deteriorated slightly as a result of DSpace version updates. However, we do not anticipate that major enhancements are needed. The biggest change is that the library intends to make the entire collection available as open data. Since both metadata and the documents will be available for free, anyone interested may harvest the material from Doria using OAI-PMH, and make it available via a database, or publish the dissertations as printed books.

Doria is not the only place via which the dissertations will be available. Bibliographic records (but not the dissertations themselves) will be loaded into the national union catalogue Melinda from which they will be harvested to Fennica, the national bibliography. This requires for instance the – in principle – simple migration from MARCXML to MARC 21.

Both the bibliographic data and the documents themselves will also be sent to Europeana. And if other libraries want to add the Royal Academy’s dissertations to their collections, such projects should be technically easy if the potential partners are familiar with e.g. METS and MARCXML.

Preservation

Libraries have a lot of experience of making documents available on the Web. Digital asset management systems have been in production for about 15 years, and libraries know how to use them. But applications like Dspace are not suitable for digital preservation, and even if they were, systems freely available in the Web are not safe enough for digital archiving.

The National Library is one of the founding partners of the National Digital Library (NDL) initiative, alongside the Finnish National Archive and the Finnish Board of Antiquities. The project, funded by Finland’s Ministry of Education and Culture, has created the shared basis for preservation of digital cultural heritage in Finland. The project has created several guidelines for digital preservation, including specification for Submission Information Packages (SIPs, as specified in the OAIS model and recommendation on file formats suitable for long term preservation.

“Any Finnish project digitising cultural heritage resources can achieve long term preservation of its digitised documents by following the NDL requirements, and avoid re-inventing the proverbial wheel.”

Because of this, any Finnish project digitizing cultural heritage resources can achieve long term preservation of its digitized documents by following the NDL requirements, and avoid re-inventing the proverbial wheel. For some organisations the changes required were substantial and even the National Library had to adjust its digitisation processes.

Like most projects dealing with digital preservation, NDL has decided to use Open Archival Information System (OAIS) model as the starting point. Preferred SIP container standard is METS, and PREMIS is used for preservation metadata. Technical metadata selections were MIX for images, textMD for texts, VideoMD for moving images and AudioMD for sound.

Meeting the NDL specifications may be difficult unless the organisation has acquired suitable tools and developed appropriate production processes. An advanced digitisation programme such as docWORKS is a must, but not sufficient unless it is accompanied by suitable work routines.

For instance, a version of the document suitable for end users is usually not suitable for preservation. Lossy JPG image will meet the requirements of most users, while digital preservation mandates lossless image, in (for instance) TIFF or JPEG2000 format. So when a resource is digitised, both TIFF and JPEG images must be produced. And every file sent to the digital archive must be accompanied by rich technical metadata so that the image can be rendered and migrated correctly.

The dissertations digitised by TAV project are encapsulated in METS containers as required by NDL. Within these containers there is all administrative metadata mandated by NDL, and much more. Meeting the NDL requirements makes it possible to preserve the documents for the long term in the shared NDL digital archive, once it has been established (which is expected to happen in 2017). As an intermediate measure, the documents will be archived in IDA service maintained by the Finnish IT Center for Science (CSC), which will also be responsible of the fully functional archive.

“Thanks to the NDL project, TAV initiative did not need to develop an internal solution to the hardest problem of any digitisation project – preservation.”

Although IDA is not a complete digital preservation system, incoming SIPs are fully validated in order to make sure that they meet the NDL requirements. This guarantees not only the safe storage of bits, but smooth transfer to the digital archive in the future. Thanks to the NDL project, TAV initiative did not need to develop an internal solution to the hardest problem of any digitisation project – preservation.

Conclusion

Although TAV project dealt with old dissertations, many of the solutions developed can be applied in other digitisation processes as well. Anything worth digitisation is valuable now and most likely also in the (distant) future. Since it is never practical to digitise the same document twice, digitised resources must be preserved for long term. And this is only possible if preservation is taken into account from the beginning. This has a significant impact on work processes, and if there are no supporting preservation initiatives such as NDL, the additional cost of guaranteeing long term preservation may be prohibitive. But if there is an opportunity for such cooperation, it should be utilised. Digital preservation may be expensive, but losing our digital cultural heritage is even more costly.