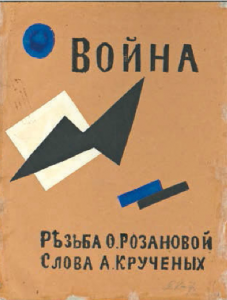

Olga Rozanova and Aleksei Kruchenykh’s work Voina (War, 1914)

The Slavonic Library of the National Library of Finland houses material on Futurism that contains rarities from the early 20th century. This material has now been conserved and digitised for customer use with support from the Autogenetic Russian Avantgarde research project. The material contains works by internationally famous Futurists, such as Vladimir Mayakovsky, Elena Guro and David Burliuk. In addition, the collection features previously unknown works, such as an anthology by a Neo-Futurist group from 1913 and Poèma poèm (“The poem of poems”, 1920), an erotic urban poem by Aleksandr “Sandro” Kusikov.

By Tomi Huttunen, Professor of Russian literature and culture at the University of Helsinki.

Counter reaction to modernism

Kusikov’s booklet was illustrated by artist Boris Èrdman. One of the special features of the Futurism collection is that it contains not only literary but also artistic rarities, such as works by Wassily Kandinsky and Pavel Filonov. Many of the Futurists were educated as artists, and the later avant-garde groups also comprised artists and poets.

In addition to text and illustration, the experimental nature of avant-garde art was evident in the printing techniques. As the books were self-made from start to finish, they had a handmade look to them. This is why the originals of Russian avant-garde literature are considered rare and valuable collectors’ items today.

Produced with lithographic printing techniques, the first Futuristic books – Aleksei Kruchenykh’s Starinnaja ljubov (“Antique love”), Mirskonca (“Of the end of the world”) and Igra v adu (“The hell game”) – were published at the end of 1912. They represented so crude a counter reaction to fin-de-siècle modernist aestheticism that contemporary artists often denounced the Primitivistic illustrations of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova as the daubs of a lunatic.

Better at distilling the Russian national character than Pushkin

Aleksei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov’s collection of poems Tè li lè (1914) was illustrated by artists Olga Rozanova and Nikolai Kulbin in a way that makes every published volume unique; one of them is housed in the National Library’s Futurism collection.

Kruchenykh was the one who wrote most of the works in the collection. This was no coincidence, for he was a skilful organiser among the Futurists; in fact, it was he who came up with the idea of a group of experimental prints. A drawing teacher from Odessa, Kruchenykh was also educated in the fine arts. He is best known for a small poem that makes no sense at all:

Дыр бул щыл

убѣшщур

скум

вы со бу

р л эз

Composed of words of an unknown language, the poem Dyr bul štšyl is featured in Kruchenykh and Khlebnikov’s collection, though it was first published in 1913 in a booklet produced with lithographic printing techniques and illustrated by Olga Rozanova. In his numerous comments on the poem, Kruchenykh emphasised that it is both transrational, composed of an unintelligible language, yet unquestionably Russian.

“There is nothing like it in European avant-garde, even though it has often been compared to Dada.”

According to him, the small poem says more about the Russian national character than all the poetry of Pushkin. Its transrational language, or zaum, was one of the specialities and peculiarities of Russian avant-garde literature. There is nothing like it in European avant-garde, even though it has often been compared to Dada. The Dadaists, however, had their Russian counterparts in a group that called themselves the Nichevoks.

Denying everything that went before

To deny the previous culture was very important in Russian Futurism. This was the idea behind the manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (1912), which appears in an eponymous book in the National Library’s collection. In the Slap, the Futurists declare that

We alone are the true face of our Time. Through us the horn of time blows in the art of the word.

The past is too tight. The Academy and Pushkin are less intelligible than hieroglyphics.

Throw Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy etc., etc. overboard

from the Steamer of Modernity.

Slap in the face of other -isms

The movement gave resounding slaps in the faces of 19th-century Realists, fin-de-siècle Symbolists and other Futurists. It comprised a discordant group of poets competing against each other in experimentation, oddity, madness and courage. As a result, Russian Futurism split into several subgroups. The avant-garde poet had to be unique as well as the first and the best of his or her time. Ego-Futurist Igor Severyanin was a typical example of such thinking. He loudly proclaims his own magnificence by declaring that

I, the genius Igor Severyanin

am in rapture over my own triumph:

I am screened in every city!

I am affirmed in every heart!

A struggle for a place in the sun

There was also a group called the Centrifuge, which included future greats such as Boris Pasternak. The less well-known Konstantin Bolshakov was also a Centrifuge, and his collection of poems Solntse na izljote (“The Sun at the end of its flight”, 1916) has found its way into the National Library’s collection. A Muscovite group called the Mezzanine of Poetry, in its turn, brought together disconnected Ego-Futurists and future Imaginists. Their main objective was to resist the dominion of Mayakovsky and co., who had already become popular. For this reason, they responded to the Slap by writing A Slap in the Face of Cubo-Futurists in 1914:

They intend to throw “overboard from the Steamer of Modernity” those who had heretofore steered it, even though they do not yet know the way to the stars or have not understood the structure and aims of the simplest of navigational instruments, the compass.

From this point on, the history of Russian avant-garde literature was characterised by a chain reaction of novel and increasingly smaller literary groups, movements and “–isms” as well as by a struggle for a place in the sun. The Imaginists, who had attacked the Futurists, became the most visible writers of the chaotic years following the revolution. Life was good for them, as they consorted with the ruling Bolsheviks.

The golden age of literary groups

In the early 1920s, more mutually competing experimental literature groups emerged, many of which were very small “–isms” consisting of two or three writers who nevertheless industriously published their own manifestos and anthologies. The New Economic Policy (NEP) of the 1920s made it possible for literary groups to engage in small-scale entrepreneurship; by March 1922, Moscow alone boasted 143 publishing houses. Since then, Russia has never enjoyed so many literary groups.

The text samples are from Venäläisen avantgarden manifestit (Helsinki: Poesia, 2014).