Summer is just around the corner alongside with the new season of Finnish baseball championship league Superpesis. This year the first pitch won’t be thrown on Finnish soil, but the season will start in Stockholm on April 22. Finnish Baseball Goes Stockholm event is a part of Finland’s centennial celebrations and aims to promote Finnish baseball, pesäpallo, as well as Finnish culture internationally. Pesäpallo is the national sport of Finland and it has been argued to be the only sport that is truly Finnish. As a cultural export, pesäpallo is very suitable for its role since it is a part of the collective memory and identity of Finns.

Jonne Kemppainen from Joensuun Maila studying pesäpallo vocabulary in Swedish (Photo credit: FBGS2017/Instagram)

On contrary to pesäpallo’s strong connections to Finnishness, the sport also has global dimensions worth observing. Pesäpallo is sometimes referred as the strange cousin of American baseball and is indeed a unique derivative of America’s favorite pastime. The father of pesäpallo, sports philosopher Lauri “Tahko” Pihkala was a former track-and-field Olympian as well as a physical educator. When Finland was still under the Russian rule in the early 20th century, Pihkala visited the United States several times and got to know American baseball. He saw many similarities with American baseball and local bat-and-ball outdoor games, such as “king ball” (kuningaspallo) played back home. Pihkala found American baseball interesting, yet a bit slow and boring. He started to develop a new sport which would be faster-paced and introduced the rules of pesäpallo finally in 1922.

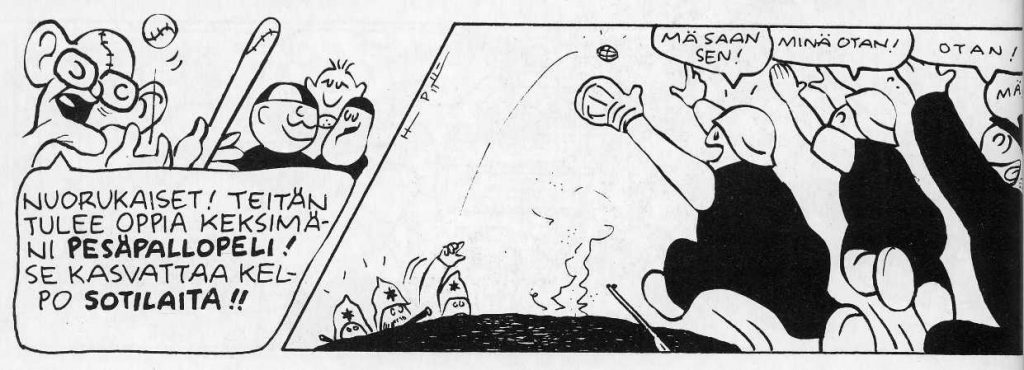

Pesäpallo is an exceptional sport in the sense that it wasn’t only evolved but it was intentionally created. It is a prime example of cultural import mixed with Finnish traditions – a hybrid cultural product. Despite its international roots, pesäpallo was created for nation building purposes not only to unify Finnish people and boost their self-esteem, but also to strengthen their physical condition and therefore increase their ability to defend their country. Pihkala also saw the sport as a means for Finland in its struggle for independence – at the time pesäpallo was introduced the era under Russian rule had just ended. In its early years, pesäpallo gained popularity especially in military schools and it was seen as means to develop fighting skills. This ideology can still be seen in the pesäpallo terminology, where players are eliminated from play either by being “wounded” (haavoittuminen) or in earlier rules “killed” (kuolema), which indeed reminds more of a field of battle than sports. Later pesäpallo was introduced in schools as part of physical education, which gradually made pesäpallo the nation’s game.

Tahko Pihkala introduces pesäpallo as means of growing young boys into proper soldiers, but the outcome isn’t as expected. (Photo credit: Hannu Pyykkönen/Jurpo)

After the mid-century a rapid urbanization process began in Finland. In the expanding cities pesäpallo’s nature changed into more goal-oriented and professional, and at the same time the sport began to be identified more with rural culture and small towns. As a part of the urbanization process, a mass migration of baby boomers also flowed abroad – mostly to Sweden, where a total of 240 000 Finns have been estimated to have settled permanently. Pesäpallo was played quite actively by the migrant Finns in Sweden until the 1990s, therefore its role in maintaining the collective Finnish memory and identity needs to be noted. As the game had unified the young Finnish nation earlier, it also created bonds and group cohesion among Finns in Sweden.

Some recreational pesäpallo is played in Sweden still today, but also on a small scale in e.g. Australia and Germany, where it is also played by Finnish migrants or their descendants. In addition to creating group cohesion in Finnish migrant communities, pesäpallo has also had an important role in connecting expatriate Finns around the world and therefore creating transnational group cohesion on some level. Since 1992 the Pesäpallo World Cup tournament has been played every now and then, and it brings the Finnish expatriate teams around the world together to compete against each other. In the first tournaments, a Japanese pesäpallo team also participated, but it has been left somewhat a mystery how pesäpallo had been introduced to the baseball-loving Japanese. The next Pesäpallo World Cup tournament will be played in Turku this summer.

“I downloaded videos online and studied the game”, says the Tahko Pihkala of India, Chetan Pagawad. (Source: YLE)

The Superpesis season start in Stockholm is just one page of the global story of pesäpallo. Instead, the Internet era has started to write a whole chapter of its own and opened up a completely new dimension to pesäpallo. The Finnish Broadcasting Company YLE reported in late 2016 that pesäpallo has mysteriously appeared in India without any Finnish migrant or expatriate connections. The local Tahko Pihkala, Chetan Pagawad told the YLE reporters that he had found pesäpallo videos on YouTube, studied the rules of the game and started to spread the knowledge around. Today there are many thousands of pesäpallo players around India and the sport is planned to be introduced in schools at some point – just like in Finland in the early days. It remains to be seen if India can someday challenge Finland in its own national sport.

TUIRE LIIMATAINEN is a PhD student at the Centre for Nordic Studies (2016- ). Her doctoral research studies identity among third generation Sweden Finns with her main research interest being minorities, marginality and identities in the Nordic context.