Among every 100,000 babies born, approximately 3 will be affected by Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis, or LCA. These babies will often suffer from a severe loss of vision at birth, affecting their quality of life right from the very beginning. LCA is an inherited form of blindness, meaning that both parents must be carriers of the gene in order to pass it down to their child. Presently, there is no cure for LCA. However the genetic nature of the condition makes it a perfect candidate for gene therapy trials. In a study conducted by University College London, researchers took on this task.

All new treatments need to undergo clinical trials in order to ensure their efficacy. For this study, the researchers conducted what is known as a “phase 1-2 open label trial”. This might seem a bit complicated to you at first, but it’s really quite a simple and efficient way to categorize clinical trials. There are up to 5 different phases in a trial, but we only need to focus on the first 2 for now. In phase 1, the treatment is administered in a very small dose to healthy volunteers. They are closely monitored for any adverse side effects, and if few are observed, the trial will proceed with a higher dose. This phase is mostly for researchers to become familiar with the treatment and how it affects the body, as well as to find the best possible dosage, length of treatment, and to determine the general safety of it. In phase 2, the treatment is re-administered to a larger group of actual patients using the predetermined safe dosages. In this phase less common side effects will often show themselves. As for the “open-label” part, this just means that no information was withheld from the participants, and they are well informed about what treatments they are receiving.

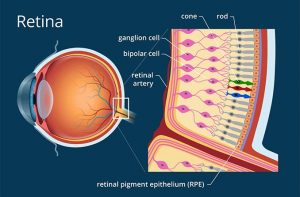

The study was conducted on 12 participants, aged 6 – 23. All patients suffered from early onset LCA, specifically with the mutation being on the gene that’s responsible for ensuring normal vision in humans. Officially, this is known as the Retinal pigment epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein, but we’ll call it the RPE65 gene. They were injected with virus vectors, which are biological tools used to administer genetic information to cells. These vectors carried the complementary RPE65 gene. 4 of the patients received a low dose of treatment, while the other 8 received a higher dose. As all good studies need to have a control, the eye that had lower vision was treated while the one that was better was used as a control, therefore left untreated. Over a 3 year time period, the participants were monitored by means of electroretinography, or ERG. This simply means that the electrical responses of different types of cells in the retina were measured. The retina is the layer of cells in the back of the eye, responsible for detecting light and sending signals to your brain in order for you to be able to see.

The studies found that in 6 of the participants, there was significant improvement in retinal sensitivity to varying degrees. This improvement only lasted 3 years, peaking at anywhere between 6 – 12 months before decreasing again. In terms of actual retinal function, there was no real improvement. 3 of the participants experienced intraocular inflammation, and 2 others experienced some other immune response. All 5 of these individuals had received the higher dose. 6 patients experienced a reduction in retinal thickness. This could potentially lead to even lower visibility in the patients. The older participants were more responsive to treatment, and the reasons for this are still unknown.

Although the results may seem inconclusive in terms of the effectiveness of the treatment on humans, I failed to mention earlier that the researchers conducted a parallel trial on dogs. Although highly dose dependent, the dogs experienced substantial improvement in their retinal functions. If you look at the improvement that patients experienced in the beginning of the trial together with the improvement in the dogs, you might see that there is true potential in this treatment. Gene therapy in general is just in it’s beginning stages and we should remain hopeful that one day it can be the cure for LCA and many other diseases like it.

Source:

James W.B. Bainbridge, Ph.D., F.R.C.Ophth., et al. Long-Term Effect of Gene Therapy on Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis. New England Journal of Medicine 372, no. 20, 1887-1897 (2015) DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414221

Images:

https://www.allaboutvision.com/resources/retina.htm

Nina – this is a great description of how an experimental trial works – I hope that this treatment is indeed improved and becomes more effective!

-Edie