January 24, 2019

Disciplinary Cannons Still Immune to Gender History?

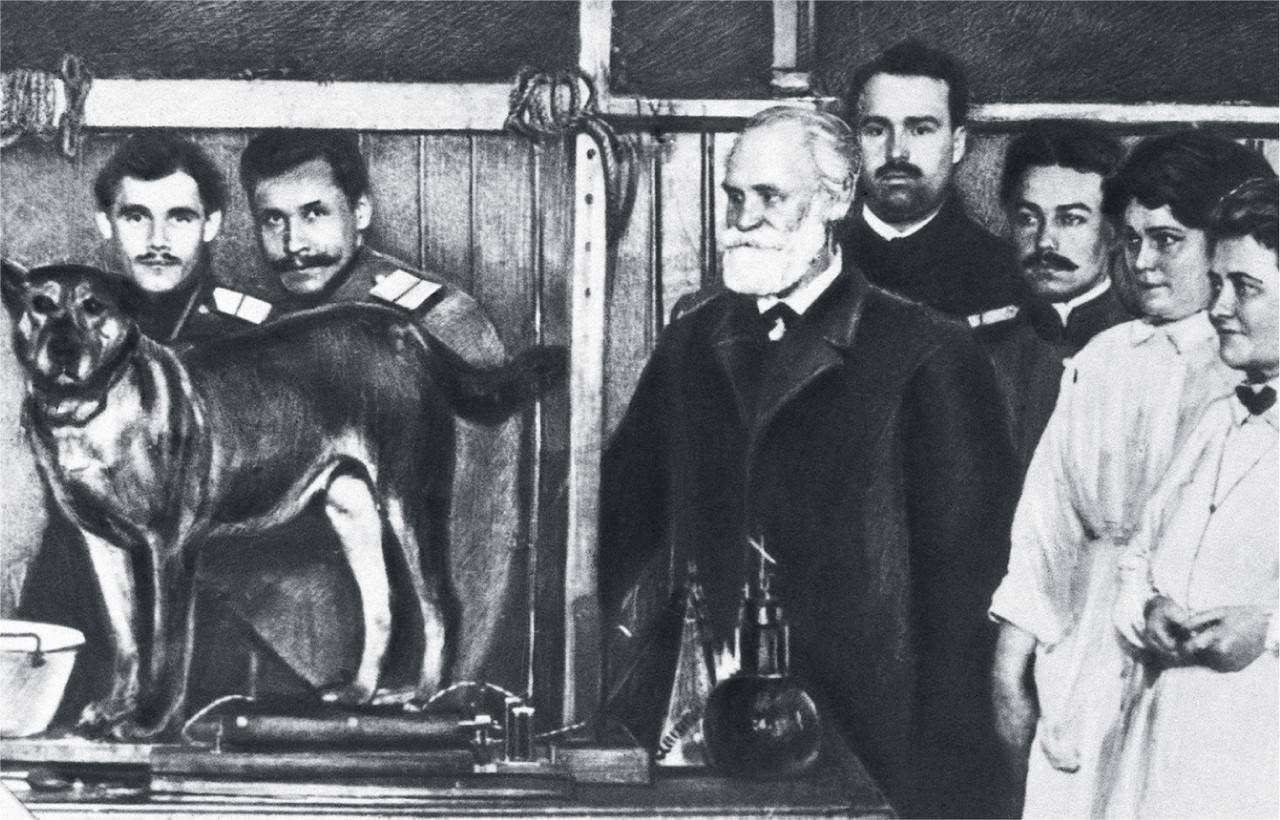

In our recent guest lecture (16.01.2019), Darryl B. Hill, PhD, Professor of Psychology at the College of Staten Island and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, discussed research stemming from his recent publication from the Journal of Research in Gender Studies, “Androcentrism and the Great Man Narrative in Psychology Textbooks: The Case of Ivan Pavlov” (2019).

The lecture and preceding discussion looked at the existence of androcentric narratives in the disciplinary history of Psychology in American psychological textbooks. By surveying contemporary American psychology textbooks and investigating how the Russian Psychologist, Ivan Pavlov, was presented, Hill argued that there is a tendency to perpetuate a ‘great man narrative’, privileging male figures in the history and cannon of Psychology. He similarly surveyed Russian Psychology textbooks, beginning in the 1950’s, and was able to corroborate this argument.

Hill presented his case by arguing that some of Pavlov’s scientific breakthroughs on conditioning and involuntary reflexes, which won him the 1904 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, were due in large part to the work of female scientists, not Pavlov. Hill continued to paint a wider picture of Pavlov’s lab in Russia as one of a kind, immense in its size, often being referred to as a ‘factory’ in mnemonic accounts. Within this context of a multitude of scientific thinkers and with the direction of archival sources, Hill puts forward the argument that female participation in Pavlov’s larger scientific movement is often underrepresented, if not ignored.

The proceeding conversation focused on the idea that women being equally written into history may be influenced by culture. Hill mentioned in his presentation that for the majority of the Soviet period, ¾ of doctors were women, while in the US this was closer to 1/4. This then raised thoughts about how practice influences cultural perceptions of gender, and thus how the memory of academic disciplines is written to appease these cultural conceptions. Though Hill presented that Russian psychology textbooks had similar narratives of androcentrism, participants of the lecture who grew up in the Soviet Union offered the counter point that many women were present in Soviet school lessons (For a broader discussion see: Novikova & Muravyeva 2014).

From a mnemonic perspective, this raised an interesting point of how textbooks as a particular cultural product may have a tendency to levitate toward simplification and popularization of histories to coincide with how these narratives already exist in the collective memory. Hill acknowledged this point, stating that like all history, psychology and the recantations of the history of psychology are limited by time and place. As such, Hill’s work shows that the history of different disciplines could greatly benefit from an investigation of their cannons from the perspective of gender. This may offer new perspectives on not only our perceptions of the past, but also disciplinary understandings of how gender and sexuality influenced the environments in which scientific thought developed.

Bibliography

Hill, Darryl B. “Androcentrism and the Great Man Narrative in Psychology Textbooks: The Case of Ivan Pavlov,” Journal of Research in Gender Studies. 9(1)(2019): 9–37.

Novikova, Natalia & Muravyeva, Marianna (eds.). Women’s History in Russia: (Re)Establishing the Field. (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014).

January 16, 2019

Gay American Dream?

Moving abroad is an experience that can sometimes revel uncertain paths. For some people, such a move is structured by possibilities of eventual return. What if one leaves her home for good? What other structures come into play when people flee their countries looking for a safer place? Law is one of these structures. People may flee from hostile legal environment in their countries of origin and look for a better legal protection in new destinations. This is the case of LGBTQ asylum seekers from post-Soviet states heading towards a ‘dream future’ in New York City.

In our recent guest lecture (9.01.2019), Alexandra Novitskaya, a PhD candidate in Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Stony Brook University, SUNY and a visiting scholar at the Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia, New York University, introduced her ongoing research project. Novitskaya’s work focuses on ethnographic research of the Russian-speaking LGBTQ migrant community in the US. Since 2015, she has conducted over 20 interviews with Russian-speaking LBGTQ asylum seekers from various post-Soviet countries, comparing the narratives of immigrant experiences derived from their oral testimonies.

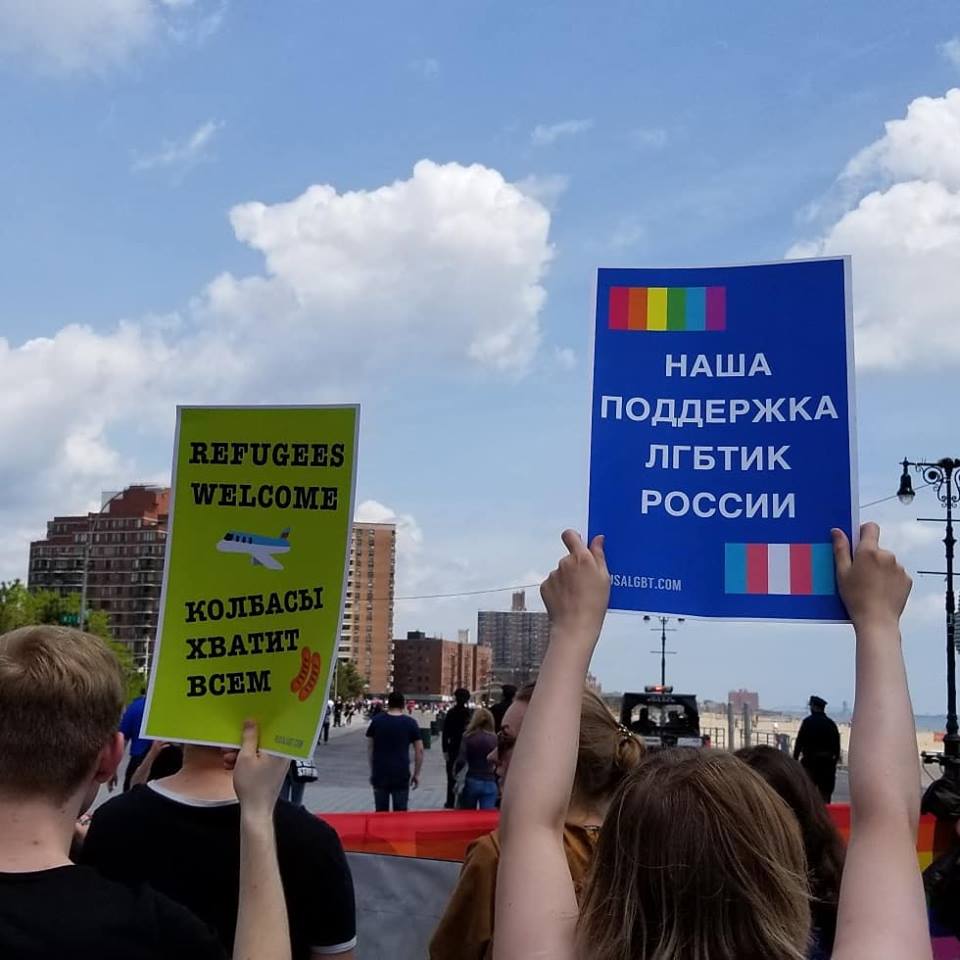

Novitskaya placed her work within the context of the ‘Gay Propaganda Law’ in Russia, introduced by the Russian Duma in 2013. Various academic and activist studies registered growth of violence against LGBTQ populations in Russia after 2013 (Kondakov 2017; HRW 2014). Novitskaya subsequently argued that the ‘Gay Propaganda Law’ created an environment where anyone who did not fit the dominant narrative of Russian ‘traditional values’ began to be ostracized from society. Growing violence against the LGBTQ community in Russia has also purportedly lead to an increased exodus, and what Novitskaya’s research in New York proposes as an increase in asylum seekers in the US. These claims are also proposed by Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty, though corresponding statistics cannot directly be validated by US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). That being said, there has been a continually increasing number in asylum applications in the US since 2014 (RFE/RL 2018).

One of the interesting findings that Novitskaya presented was the idea of a ‘gay American dream’, which many of her interviewees alluded to or commented on directly in their narratives. Novitskaya argued that this image of America as a gay friendly paradise may have been influenced by the rise of homo-nationalism conveyed by Hillary Clinton during her time as Secretary of State, as well as the Obama Presidency. This period of homo-nationalism in American domestic and foreign politics was characterized by increased funding for LGBTQ support abroad. Novitskaya argued that American homo-nationalism only incorporated the ‘gay American dream’ into already narrowly defined life narratives that American society associates with achieving success, utilizing the positive liberal image associated with LGBTQ rights for political points. Regardless, Novitskaya highlighted the increased public presence of the Russian speaking LGBTQ communities in the U.S., specifically RUSA LGBT – Russian-Speaking American LGBT Association in NYC, Boston, Chicago, and other large urban centers.

Novitskaya argued that many of her interviewees continued to have faith in America even while the Trump Administration remains unapologetically anti-immigration and anti-LGBTQ. Regardless of this populist turn in American politics, Novitskaya’s research participants continued to profess faith in the U.S. as a state based on the rule of law and checks and balances, considering Trump’s exclusive nationalism only temporary.

In the discussion that followed Novitskaya’s presentation, ideas were presented steaming from migrant studies literature, considering why many of these Russian asylum seekers had such a positive vision of America and the gay American dream. One participant commented that in the literature, there is an argument stating that regardless of how hard life in a new country may be, migrants are unlikely to return to their country of origin because that would be admitting failure in their quest to build a new life. Additionally, this may also lead to the perceptions of viewing the power of the American legal system through rose tinted glasses. Thus, the presentation left many open contemplations of which imagined communities Russian speaking LGBTQ asylum seekers participate in, and what America subsequently comes to signify for these communities.

In sum, the first 2019 lecture in the series New Perspective on Russia and Eurasia offered interesting thought and continued cross-Atlantic discussion on gender, migration, Law, and Russia in a global context. Follow us on Facebook or look at our events page for future events.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict (1983) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism.

Human Rights Watch (2014, December). License to Harm: Violence and Harassment against LGBT People and Activists in Russia, 2014. Human Rights Watch. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/12/15/license-harm/violence-and-harassment-against-lgbt-people-and-activists-russia#. Accessed 14.01.2019.

Schreck, C. (2018, May). Russian Asylum Applications in U.S. Hit 24-Year Record. Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty. Available from: https://www.rferl.org/a/russian-asylum-applications-in-u-s-hit-24-year-record/29204843.html-. Accessed 11.01.2019.

December 12, 2018

Development of Russian Law XI: Concluding Thoughts

Access to Justice in Eurasia: From Regional to Global, 11th Development of Russian Law Conference

The 11th annual Development of Russian Law Conference marks the continued development of one of the only annual international gatherings of experts on Russian Law. The conference, held in Helsinki on November 19-20 this year, assembled a variety of experts of different disciplinary backgrounds, including Legal Studies, Social Anthropology, Sociology, Social Science and History. They covered a wide range of themes, such as human rights, business, neo-liberal theory and the interaction of political and legal cultures. Even with the regional and thematic focus on ‘access to justice’ in Russian and Eurasia, the 11th annual Development of Russian Law Conference truly fostered an interdisciplinary cross pollination of academic thought, continuing to show the potential for ongoing growth and cooperation.

Access to justice has become an important issue in many justice systems around the world. Access to justice enables individuals to protect themselves against infringements on their rights, to remedy civil wrongs, to hold executive power accountable and to defend themselves in criminal proceedings. The popular image of the Russian judicial system is dominated by two contradictory narratives. One emphasizes its dysfunctional elements, focusing on the public’s distrust of the courts. This narrative delights in presenting high-profile cases in which the outcomes are blatantly dictated by the desires of the Kremlin as representative. The other looks more at the day-to-day reality of the courts and stresses the burden judges carry, caused by the avalanche of cases brought before them. There is a logical inconsistency to the two images. Remarkably, both have more than a kernel of truth to them. To a considerable extent, they feed on one another. Overworked and exhausted Russian judges make mistakes that contribute to low public esteem for courts. Yet court administrators continue to push judges to absorb ever-greater numbers of cases as a way of proving the value of courts. Among other things, e-justice has been seen by the administration as an effective remedy against backlog and inability to provide efficient access to justice. Similar narratives are applicable to other post-Soviet countries, many of whom have been undergoing a wide range of changes in an attempt to integrate into a variety of regional and global legal orders.

Experts from Russia, Finland, the EU and the US came together to examine how access to justice is provided in a variety contexts, be it neoliberal economics, businesses and consumer rights in Eastern Europe, access to justice for social groups or international frameworks for justice institutions. The main debates focused on the problem of ‘if access to justice constitutes the main component of the rule of law’ or, in other words, what kind of access to justice proves rule of law workable. There is an agreement among experts that in Russia, access to justice is well organized: it is cheap, egalitarian and direct. However, another point of heated discussion is if these factors truly lead to transparency and the actual reception of justice in terms of satisfaction with the justice system. The majority of academics and practitioners are skeptical about the current situation in Russia, pointing out that there are major problems within the justice system and legal profession, continuing to dwell on Soviet institutional heritage. In addition to legal argument, politics plays a crucial role in ‘who can’ and ‘how to’ receive justice, as well as ‘who can’ and ‘how to’ administer it.

In sum, the Development of Russian Law conference produced another year of fruitful conversations and academic synthesis. After eleven years, the project has established itself and now organizes a wider international community of experts. Rooted in the Finnish tradition of expert knowledge of Russia and the interdisciplinary academic prospective of the University of Helsinki, Development of Russian Law has a positive outlook for the future, with the next step of promoting further interaction among scholars of all disciplines.