Kenen rauha? Turvavyöhykkeen ulkopuolelta

Toivon repaleet Tikkurilassa 14.-27.8.: Aceh calling – globaali punksolidaarisuus

(For English scroll down)

Maanantaina 14.8. alkaa kaksiviikkoinen työrupeamani Tikkurilan kirjaston musiikkiosastolla (1.krs, avoinna ma-pe 8-20, la-su 10-16). Yhteistyö Vantaan kirjaston musiikkiosaston ja Vantaan Muuntamon kanssa esittää Scraps of Hope/Toivon repaleet -lyhytdokkareita jotka liittyvät kaupunkietnografiseen tutkimukseen Acehin rauhan 1.vuosikymmenestä Banda Acehin kaupungissa. Yhtensä 13 lyhytdokkaria pyörivät non-stoppina musiikkiosastolla kahden viikon ajan.

Tapahtumaan liittyy kaksi video-keskustelutilaisuutta, joista ensimmäinen ma 14.8. klo 18-20 keskittyen joulukuussa 2011 tehtyyn punkpidätykseen, sen jälkeiseen globaaliin punksolidaarisuuteen ja katupunkkareiden arkeen Banda Acehin kaupungissa.

Videokeskustelu (joka on samalla samalla banda acehilaista punk-skeneä ja konfliktinjälkeistä maskuliinisuutta käsittelevä kirjan luvun luonnos) etenee seuraavien acehilaisten punkbiisien johdattelemana: Illiza bastard, Our Wound (Luka kita), Prison of thoughts (penjara pemikiran), Cheap film (film murahan), Difference is not a war (pembedaan bukan perang), ja A.C.A.B.

Tervetuloa Tikkurilaan!

On Monday (14th August) starts my two weeks long worksession in Tikkurila. It is a collaboration with the city library and popup office of City of Vantaa, Muuntamo. Over the two weeks Scraps of Hope short documentaries, narrating stories from the first decade of peace in Aceh, Indonesia, are screened non-stop (music section, ground floor, open on weekdays 8am-8pm, Sat-Sun 10am-4pm).

I organise two video-talks (14th/21st at 6pm) )at the library and one longer session on the overall book project at popup office Muuntamo (Sat 26th Aug 10am-2pm).

The first one on 14th at 6pm focuses on the punk arrest of December 2011, global punk solidarity in its aftermath and everyday lives of the Tsunami Museum street punk community. Video talk unfolds in the order of the punk songs:

Illiza bastard, Our Wound (Luka kita), Prison of thoughts (penjara pemikiran), Cheap film (film murahan), Difference is not a war (pembedaan bukan perang), ja A.C.A.B.

Join me in Tikkurila!

Etnografisesta kaupunkitutkimuksesta etnografisesti Tikkurilassa

Tässä ensimmäinen postaus Tikkurilasta, jossa työskentelen seuraavat viikot (14.-27.8.) yhteistyössä Tikkurilan kirjaston musiikki-osaston ja Vantaan Muuntamon kanssa.

Näillä kaupunkitilaan sijoitetuilla työpäivillä on tarkoitus tuoda etnografista, ja feminististä, politiikantutkimusta lähemmäs elettyä ja koettua arkea. Työskentelytapa sopii minulle, sillä olenhan samaan tapaan tehnyt töitä Banda Acehin kaupungissa viimeisten 11 vuoden ajan tutkiessani Suomessa tutuksi tulleen Acehin rauhansopimuksen elettyä ja koettua arkea. Kaupunkitilassa työskentely, hengailu, keskustelu ja kirjoittaminen ovat olleet osa tutkijanarkea.

Aikataulutettuja tapahtumia on seuraavasti:

Lyhytdokumenttielokuvia (yht. kesto 94 min) 14.-27. elokuuta

Tikkurilan kirjaston aukioloaikoina, musiikkiosasto (1.krs)

Keskustelutilaisuudet:

Ma 14.8. klo 18-20

Aceh calling – globaali punksolidaarisuus

Ma 21.8. klo 18-20

Kenen rauha? Aktivisti Zubaidah Djoharin runoja Acehin rauhasta

La 26. elokuuta klo 10-16

Elävä kirja: tapaa tutkija työssään

Muuntamo, Tikkurilan tori, Asematie 3b

Esitykset ja keskustelu: 10-12, 12-14, 14-16

Lisätietoa lyhytdokumenteista ja etnografisesta kaupunkitutkimuksesta

22 December – On motherhood, populist nationalism and peace-time body politics of political economy

22 December 1928 – forgotten day of women’s activism

Hari Ibu, mother’s day, celebrated today in Indonesia has an intriguing, yet often forgotten, feminist history. Originally the day was chosen to commemorate the First Congress of Women held in 1928 in Mataram just few months after the historic Youth Congress that is considered as one of the culmination point for demands for decolonialization and formation of Indonesian nationalism.

The women’s congress focused on questions of right to education, child marriage, divorce and secular marriage law, but also Western influence on women. During the authoritarian presidency of Suharto also known as the ‘New Order’ turned the day into Hari Ibu (Mother’s day), with the focus on state ideology on motherhood (state ibuisme), being a good wife and mother. The day has been since celebrated through competitions and quizzes that test women’s abilities to be good mothers and wives.

Scraps of Hope video ‘MoU Helsinki – Reclaiming back History’ is a reflection of the gendered impacts of the Aceh peace process, sexual politics and focus on morality of women, but it also importantly, brings back to the peace table (video is shot at the location of signing of the peace settlement in Finland) the discussion on exploitative peace time political economy and gendered impacts of natural disasters. It provides an alternative vision for the celebration of Hari Ibu in ways that reclaims back the history and addresses some of the most burning questions on economic justice and wellbeing.

Populist reclaiming of history – the case of Cut Meutia and new banknotes

Indonesian government has released new banknotes on Monday. New 100,000, 50,000, 20,000, 10,000, 5,000, 2,000 and 1,000 Rupiah banknotes feature an interesting selection of historic figures, nationalists, and civilian and military participants in anti-colonial movement: president Sukarno, prime minister and signatory of proclamation of independence Mohammad Hatta, the last prime minister Djuanda Kartawidjaja (after whom the post was abolished allowing greater powers for the president), member of Volksraad (Dutch East Indie’s Parliament) and preparatory committee for Indonesian independence Sam Ratulangi, Papuan pro-Indonesia politician Frans Kaisepo, politician and chairperson of Nahdlatul Ulama Idham Chalid, member of Volksraad and advocate of plantation labour rights Mohammad Hoesni Thamrin, politician I Gusti Ketut Pudja, colonel of Indonesian national revolution TB Simatupang, founder of socialist Indies party Tjipto Mangunkusumo, professor (rural technology) Herman Johannes and last but not least, Acehnese female military commander Cut/Tjut Meutia (1870-1910) who fought in the war against the Dutch.

The 1.000 Rupiah banknote with Cut Meutia has caused debate in Aceh. Not because Cut Meutia is only the third Acehnese national hero to be featured in the Indonesian banknotes after Teuku Umar and Cut Nyak Dhien a couple who fought against the Dutch. Or that it was the lowest nomination given to a woman in the group of eleven men. Instead, Acehnese legislative assembly member Asrizal H Ansnawi (PAN) has questioned the right of the Bank of Indonesia for picturing Cut Meutia without Islamic headscarf and asked the banks in Aceh not to circulate the new banknote in Aceh.

Few days into this request, a number of emerging Acehnese scholars such as Raisa Kamila and Herman Syah have responded to this demand. In their response to this attempt to ‘reclaim history’ they illustrate that from the sources available (photographs, illustrations and narrations in books), Cut Meutia in fact did not wear a headscarf and like many of the female military commanders and elites of her time, her dress did not consist of what is these days considered as ‘traditional’ Acehnese, or modest Islamic, dress.

Raisa Kamila further suggests, that the case of the banknote is a continuation of a longer Acehnese and Indonesian history in which the female body becomes the battleground for politics and violence, but a one that is not controlled by women: Gerwani women were stripped in 1965 in search of communist tattoos, Chinese women were raped during the Jakarta riots in 1998 and women were shaved and publicly paraded in the streets of Banda Aceh in 2001 when the legislation on Islamic dress code was brought up in Jakarta.

Reprint of the talks held at the First Congress of Women of 1928:

Susan Blackburn (2008) The First Indonesian Women’s Congress of 1928. Monash Asia Institute

-“- (2007) Kongres Perempuan Pertama. KITLV-Jakarta.

Read my earlier analysis (Jauhola 2010) of the celebration of Hari Ibu and gendered uses of national emblem Garuda, bird-like creature.

Turning the gaze at European post-war project

Edit: on 8 Nov 2016 added first paragraph which was not part of the original written talk but improvised on spot

Keynote on Gender and Conflicts at Power Structures, Conflict Resolution and Social Justice Symposium 13-14 October 2016 EU-India Social Science and Humanities Platform (EqUIP) – please check against delivery.

Before I move on to my prepared talk, I want to add: although I am now located in Gender Studies at the University of Helsinki I have not studied a single module/course of so called Western-campus-taught Gender/Women’s Studies. Rather, the induction to me was Indian feminists and women’s organisations that I got to know when I lived in India 1999-2001. I want to raise this point here in the context of the discussion started at this symposium earlier today of the need to decolonialize academia. I want to encourage you all with this example: we can actually do quite a lot ourselves by reaching out to “alternative archives”. This learning process has been very informative for me and I can see traces of that in my research, and teaching.

—

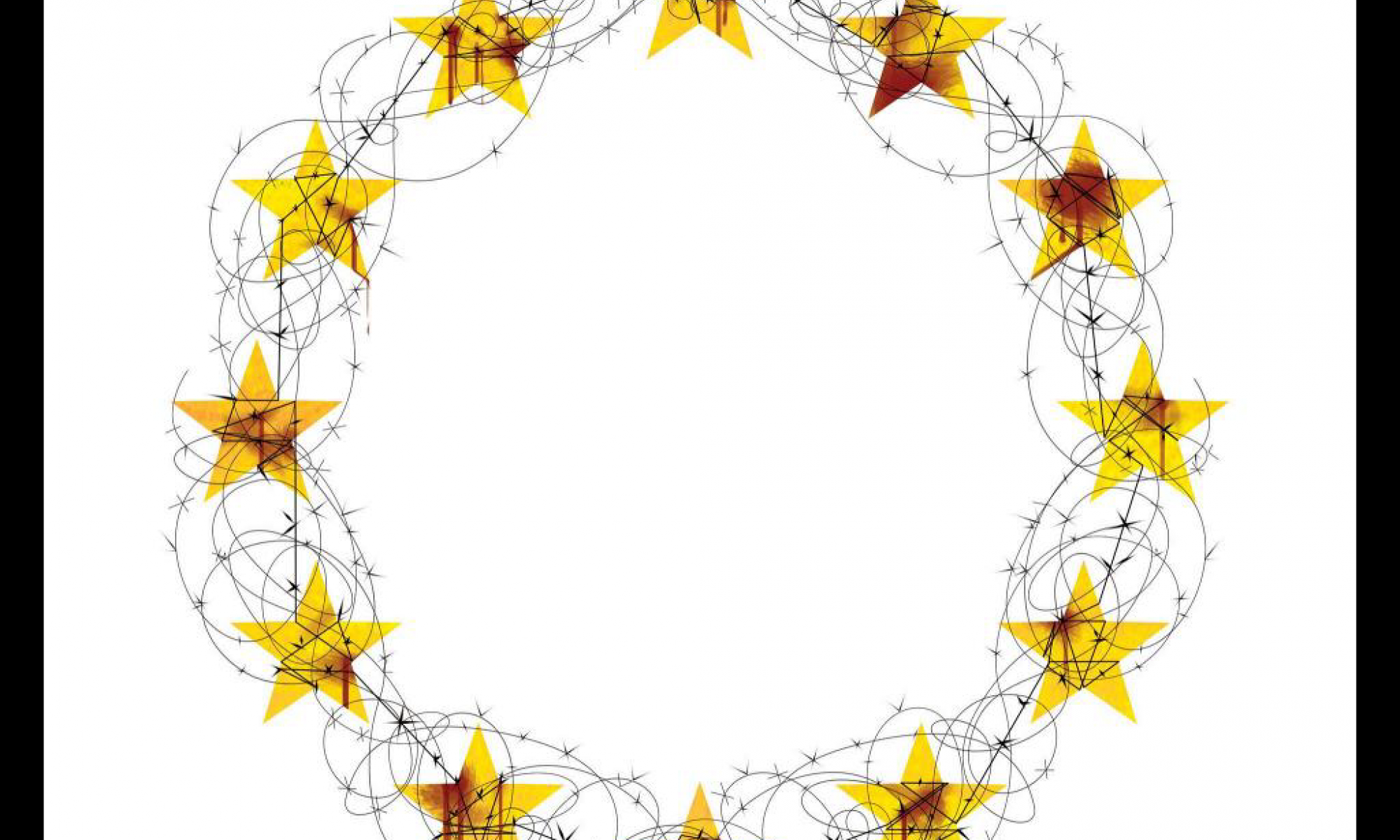

At this particular moment in time, being one of the European keynote speakers at this event, is particularly painful, but I would also say extremely important: turning the gaze towards Europe, Europeaness and the potential violence that these ideas entail.

The painfulness stems from the inability of European leaders or European public, along with their global partners to deal humanely the catastrophes that have been unfolding in front of our eyes for years now. Ironically, the European Union (EU) was awarded the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize “for over six decades [having] contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe” and how this contribution is in stark contrast with the realities of post-war European project, such, as

1. Crises that has been unfolding in Syria for too long – the recent broken cessation of hostilities agreement, attacks on humanitarian aid convoys, hospitals and life line services – it truly breaks my heart participating and negotiating the principles and ACTIONS to be taken in the development of the Finnish 3rd National Action Plan on the implementation of UNSCR1325 – when at the same time, so little hope is visible for Syrians in and outside of Syria

2. Building the fortress Europe, and resulting as a crisis of humanity – the inability to address the catastrophe on the shores of the European union in particular related to migration policies and the return to national self-interests and reinforcing the European Union’s external border with a severe humanitarian cost.

3. Gendered Political Economy: Cedaw committee’s reports on Greece in particular, are alarming: the aftershocks of the 2008 financial crises, especially in the Eurozone, that are felt as new structural forms of gender violence: austerity measures that have brought along with them new forms of gender conservatism and discrimination – measures that have been at the heart of the demands of the troika of IMF, European Central Bank and European commission have been at the forefront – making demands to cut social and health services (major employment sector for women) – but also new restrictions to women’s rights such as sexual and reproductive rights as the recent cases from Spain, and Poland, illustrate

4. Growth of populist right wing politics, Islamophobia and racism and violence that takes form – just to give you a few examples from Finland – campaigns to “close borders” and “protect white Finnish women from brown men” entering Finland as asylum seekers from Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and other countries in crises.

5. Sexual politics of peace/post-war reconstruction through images of ‘good and respectable women’: Inability to address history of gendered violence in conflicts internally – I use here 1) the case of “German brides” in Finland, and the demonization of Finnish women who fraternized with German soldiers, and 2) how post-war reconstruction in the aftermath of WWII/Finnish Lapland has meant several decades long oppression of the only indigenous people – Sámi people – in the whole of European Union.

In the words of Skolt Same activist, theatre director Pauliina Feodoroff: Skolt Sáme world ended after the 1930’s. We Skolt Sámi in three post-Second World War countries of Russia, Finland, Norway live in the spatiality and temporality of apocalypse. Hydropower, nuclear weapons, forced displacements of villages in the name of development, mining activity and cultural change accelerated by wars and displacement have been total: fast and extremely fatal, encompassing all spheres of life. Another Sámi feminist scholar Rauna Kuokkanen (Kuokaanen 2007, Knobblock and Kuokkanen 2015) has suggested that indigenizing the Finnish postwar history writing reaquires mourning of loss and victimhood, without which it is impossible to visualize the future and reabuild oneself and reconstruct the debate in Sámi terms: deal with the question of settler colonialism, conflict between indigenous and post-war recovery market economies, and indigenous political agency.

Let’s have a pause here.

Afore mentioned crises are all taking place simultaneously with another set of global agenda making, i.e. the UN Security Council Resolution 1325, and the consequent 7 other resolutions adopted between 2008 and 2015 also known as women/gender, peace and security agenda.

A recent International Affairs journal’s special issue (March 2016) dedicated to the theme made the following observations:

– WPS agenda is not uniform, in theory, concept or practice

– WPS/UNSCR1325 agenda is most successful at a policy document and resolution level – but not as being translated into various fields of ‘practice’

– Although celebrated as a comprehensive agenda to address gendered conflicts, peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction processes, the implementation, and planning for National Action Plans by the member states has been selective: giving stronger focus on violence prevention and protection (from gender and sexual violence) than on women’s participation in peace and security governance.

– Narrowing down the agenda has ambiguous/paranoid political implications: there is a clear need to focus on conflict related sexual violence, however, losing the focus on participation risks losing the critical significance of articulating women as agents of change in conflict and post-conflict environments AS both right-bearers and rights-protectors

– The focus purely on the conflict-related sexual violence closes the feminist scholar’s observation of the ‘continuum of violence’ – in fact, the peace processes, peace settlements can be dangerous fruits for new forms of gendered discrimination in legal, political and economic spheres.

– Special issue editors Laura Shepherd and Paul Kirby make suggestions: an alternative would be to making the links between sexualized violence and participation visible: and in fact pay attention to how sexualized and gender-based violence inhibits women’s (or more widely those subjectification to Gender-based violence) participation in formal and informal politics. Secondly, it would require acknowledgement that WPS agenda cannot be advocated and implemented without more comprehensive focus on reparation and development, connecting protection and prevention of violence to the questions of rule of law, economic, political, social rights and holistic wellbeing

Furthermore,

– Focus on the UNSCR1325, or implementation is on foreign policy oriented, and UNSCR1325 has therefore become a tool for country-branding

– In the case of Finland, this has led into a severe construction of a myth of “achieved gender equality” – that can be experts elsewhere through gender knowhow and expertism – which remains completely unable to tackle domestic intersections of gender with other social inequalities and oppressions, or the aforementioned crises

– in advocating implementation of UNSCR1325 through peace mediation, humanitarian assistance at the same time when the government has in fact cut down its development aid budget, made several revisions that harden the policies towards refugees and asylum seekers and have allowed continuous growth of neo-nazi, racist movements that not only pose verbal but also physical threat to those opposing them.

I suppose the big (research) questions that I have in mind while wanting to juxtapose these parallel phenomena and political processes, is the following:

1. what happens to the feminist and gender theorising and/or activism on peace & conflicts when they become institutionalized into regional, or state-focused foreign policy agenda – that may become handmaidens or essential part of nationalist, populist, and racist agendas?

2. Following from that, is the following question: What new feminist conceptual and analytical tools do we need to study the lack of policy coherence between interior, migration/refugee, humanitarian, development, trade (arms trade in particular), allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the linkages, often silenced, between policy agendas – that have gendered effects.

It is these times that set up a test for Europe, or European states as “promoters of ideas and values” – juxtaposition that is made in comparison to focus on military and economic power. Normative power Europe is in crises, if it cannot deliver the same normative basis of human rights, humanity and principles of wellbeing to people who are being subjected to right-wing politics, guarding and closing borders.

Thirdly, it is necessary to ask the fundamental question of the discriminative threat of the wording in Lisbon Treaty that establishes the aim of the European Union to “to promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples”. Who counts as ’its peoples’? Who is left out from this notion of European well-being? Using sociologist Gurminder Bhambra’s words: ”such social theorists of European crisis fail to address the colonial histories of Europe. This failure enables to dismiss Europe’s postcolonial & multicultural present” (Bhambra 2015)

Finally, these questions, the divide between the “policy talk” and “implementation” and increasing definition of concepts and terminology to serve specific groups and their entitlements in the face of crises that are global, and that require global, not nationalistic solutions. How do we translate them into theoretical-methodological discussions that go beyond ‘discourse’ as texts and speeches and focus on structures, and embodied materiality. What is the real gendered cost of the fortress Europe, or any other attempt to construct post-war/conflict states and identities – and how should we address them?

Non-Linked References

Bhambra, Gurminder K.. 2015. Whither Europe?. Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 18(2), 187-202.

Knobblock, Ina and Kuokkanen,Rauna ‘Decolonizing feminism in the North: a conversation with Rauna Kuokkanen’, NORA—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 23: 4, 2015, pp. 275–81.

Kuokkanen, Rauna ‘Saamelaiset ja kolonialismin vaikutukset nykypäivänä’, in Joel Kuortti, Mikko Lehtonen and Olli Löytty, eds, Kolonialismin jäljet: keskustat, periferiat ja Suomi (Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2007).

Image credits: Cristiano Salgado, Expresso, Portugal

What are we mainstreaming when we mainstream gender?

Gender mainstreaming has become one of the most important policy tools for promoting gender equality and women’s rights globally. Even Security Council, in its resolutions to promote gender equality and women’s rights in peacebuilding, calls for action through gender mainstreaming (UNSCR 1325, 1888, 1889, 1960, 2106, 2122, 2422). Resolutions also specifically request gender expertise, gender analysis, and gender-sensitive training to ensure capabilities for implementing gender mainstreaming.

Since the formal acknowledgement of gender mainstreaming principle in 1995 at the Fourth UN World Conference on Women in Beijing, I’ve had number of roles as a) an advocate for the integration of gender equality policies in Finnish development cooperation and overall Finnish government policies b) gender trainer in European civilian and military crisis management operation and UN military observer pre-departure trainings, c) evaluator of the effectiveness of the gender mainstreaming programme in post-conflict statebuilding context of Bosnia-Herzegovina; and d) gender advisor of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

During those years, however, I was getting more and more troubled that concepts such as ‘gender mainstreaming’ or ‘gender equality’, or ‘women’s empowerment’ are political concepts: they carry meanings that are results of negotiation processes, although when turned into policy advocacy or tools, they often appear as neutral and natural.

From 2005 onwards, when I began my PhD studies, instead of asking how well gender mainstreaming is implemented, I became more interested in understanding what gender mainstreaming does. Thus, rather than seeing gender mainstreaming as something that has been already been set in stone, i.e. we always already know what it is, my research aimed at arguing, illustrating with the examples from Aceh, Indonesia, that it is an active process of negotiating norms: gender norms, but also importantly other norms, such as nationalism, religious identity, class, socio-economic status, sexuality and so on.

Here are the slides of a lecture I gave on gender mainstreaming on 28 September 2016 at the Gender, Conflicts and Security in a Globalised World course organised by Valpuri, Faculty of Social Sciences Gender Studies Teaching Basket at the University of Helsinki.

My 2010 PhD thesis (International Politics, University of Aberystwyth, Wales) ‘Becoming Better ‘Men’ and ‘Women’: Negotiating Normativity through Gender Mainstreaming in Post-Tsunami Reconstruction initiatives in Aceh, Indonesia was funded by European Community Marie Curie Host Fellowship for Early Stage Researchers Training, 2006-2009 and Academy of Finland funded project ‘Gendered Agency in Conflict: Gender Sensitive Approach to Development and Conflict Management Practices’, 2007-2010.

An edited version was published in 2013 by Routledge as Post-Tsunami Reconstruction in Indonesia: Negotiating Normativity through Gender Mainstreaming Initiatives in Aceh.

Suomen 1325-politiikka – tehotonta maabrändäystä vai mistä onkaan kysymys?

Syys-lokakuusta on tullut, sitten vuonna 2000 YK:n turvallisuusneuvoston hyväksymän päätöslauselman nro 1325 (aka UNSCR1325, naiset, rauha ja turvallisuus -päätöslauselma), kiireinen kansainvälisen tasa-arvo- ja ihmisoikeuspolitiikan näyttämö.

Myös tänä syksynä tapahtuu, presidentti Niinistö osallistuu YK:n yleiskokoukseen ja isännöi syyskuun lopussa illallisen osana He for She -kampanjaa, jonne kutsutaan 30 ns. impact championia. Indonesiasta kuuluu huhuja, että Indonesian presidentti Joko Widowo on yksi korkea-arvoiseen tehtävään valituista. Indonesialaisen median jälkeen puheenvuoron ottivat indonesialaiset feministit ja naisaktivistit: mitä Widowo oikeastaan tietää naisten aseman tai tasa-arvon edistämisestä ja mitkä konkreettiset teot tätä vaikuttavuuden mestaruus -nimitystä tukevat?

Suomessa tulevat viikot ovat myöskin merkittäviä. Ulkoasiainministeriö on nimittäin luovuttanut kaksi 1325-toimintaohjelman vuosiraporttiaan (2014,2015) Eduskunnan Ulkoasiainvaliokunnan (UVA) käsiteltäväksi, vuosille 2012-16 laaditun toimintaohjelman mukaisesti. Raporttien käsittelyaikataulu ja -tapa herättää kysymyksiä: miksi raportit käsitellään yhdessä ja kuinka on mahdollista, että vuoden 2014 raporttia ei ole vielä syksyyn 2016 mennessä käsitelty? Onhan ulko-, turvallisuus- ja maahanmuuttopoliittisessa ympäristössä tapahtunut merkittäviä muutoksia viime vuosien aikana. UVAn viikkoaikataulu ei myöskään anna osviittaa siitä, että valiokunta kuulisi ulkopuolisia asiantuntijoita raportin käsittelyn yhteydessä.

Miksi tämä on ongelma, siitä tähän muutama havainto:

Olen kirjoittanut artikkelin Suomen 1325-politiikasta ja maabrändäyksestä International Affairsin (92/2) teemanumeroon “The futures of women, peace and security” jossa tuon esille usean esimerkin avulla mitä ongelmia syntyy, kun kansainvälinen normisto, tai em. päätöslauselma ja sen toimeenpano otetaan ulkopoliittisen maabrändäyksen käsikassaraksi. Se politiikan lohko, jota artikkelini ei käsitellyt, on maahanmuutto- ja turvapaikkapolitiikka. Pohdin tätä “hiljaisuutta” artikkelia luonnostellessani luvaten itselleni, että siihen on palattava.

Kulunut vuosi on tuonut tämän hiljentämisen politiikan valitettavalla tavalla esille. Samaan aikaan kun Suomen hallitus kirjaa 1325-politiikan toteuttamisen olennaiseksi osaksi globaalia vastuuta (hallitusohjelma s. 35), 1325-politiikka esitetään puhtaasti ulko- ja turvapolitiikan kehittämisen työvälineenä (raportti 2015, s. 2). 1325-tematiikan näkyvyyttä kiitellään erityisesti Suomen ulkopolitiikassa ja kansainvälisessä profiilissa (raportti 2015, s. 3). Suomen harjoittamaa turvapaikka- tai maahanmuuttopolitiikkaa ei tämän logiikan mukaan nähdä osana globaalia vastuuta, tai globaalia turvallisuutta. Ei vaikka, Suomen kansallinen toimintaohjelma vuosille 2012-16 toteaakin:

Suomi on sitoutunut kansainvälisen humanitaarisen oikeuden täysimääräiseen toimeenpanoon. Aseellisten konfliktien aikana sovellettavan kansainvälisen humanitaarisen oikeuden mukaan naiset ja lapset ovat erityisen haavoittuvassa asemassa. Naisten oikeuksien suojelussa kansainvälinen humanitaarinen oikeus painottaa erityisesti naisten asemaa lasten äiteinä ja huoltajina. Konfliktista kärsivien naisten tarvetta erityissuojeluun, terveydenhoitoon ja apuun on myös kunnioitettava (toimintaohjelma 2012-16, s. 33)

Jään odottamaan miten Ulkoasiainvaliokunta raportteja käsittelee. Tämä on merkittävää myös siksi, että tänä syksynä käynnistetään 3. kansallisen toimintaohjelman valmistelu.

Scraps of Hope videos & talks @Porthania, University of Helsinki

Scraps of Hope video screening, meet & greet talks

5-19 September

Porthania, Yliopistonkatu 3, 00100 Helsinki

https://www.facebook.com/events/1059538470806668/?ti=icl

Video screenings daily at 11.45am, Unicafe video screen plus Mondays & Fridays Lehtisali (2nd floor)

Meet & greet talks on Mondays and Fridays at 12.30-13.30 Lehtisali (2nd floor)

Meet and greet programme:

Mon 5 Sept

10 Years of Gender and EU Civilian Crisis Management Missions: From Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM) onwards

Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM) was among the first EU civilian crisis management missions. Through it the EU and five ASEAN Member States monitored the peace settlement between the Indonesian government and Free Aceh Movement in 2005-2006. How did AMM incorporate gender concerns of armed conflict and peace agreements, mandated by the UN Security Council resolution 1325? How has the EU crisis management instrument evolved since the AMM? What has that meant for gender equality and justice concerns?

Docent, Academy of Finland Research Fellow Marjaana Jauhola talks with Dr. Leena Avonius, Researcher, Crisis Management Center Finland, former AMM Reintegration Co-ordinator (2005-6)

Fri 9 Sept

The use and abuse of history: Post-authoritarianism, Regime Change and Democratization in Indonesia

Following the exit of President Suharto in 1999, Indonesia has gone through a series of democratizing measures such as decentralisation, freedom of press, political parties, amendments to constitution and new state institutions. What role have these played in the settlement of armed conflict in Aceh, and what are its consequences for gender equality concerns? How has Indonesia come to terms with its violent history and atrocities of its citizens during the massacre of 1965-66 targeting members and suspects of affiliates of Indonesian Communist Party? The Aceh peace process included provisions for human rights court and truth reconciliation process. Is there scope for justice in Aceh peace process?

Docent, Academy of Finland Research Fellow Marjaana Jauhola talks with Dr. Ratih Dwiyani Adiputri, University of Jyväskylä a former legislative expert in the Indonesian parliament (2000-9) and advisor of USAID parliamentary project in Aceh (2006-7).

Mon 12 Sept

Complex emergencies and humanitarian assistance: what has gender got to do with it?

Every year, conflicts and natural disasters cause suffering for millions of people – usually for the poorest, marginalized and vulnerable populations. Humanitarian assistance aims to provide life-saving assistance, reduce human suffering and maintain dignity during and aftermath of crises. How well do these efforts address gendered vulnerabilities and capabilities? What would gender mainstreaming of humanitarian assistance look alike?

Docent, Academy of Finland Research Fellow Marjaana Jauhola talks with Satu Lassila, Senior Adviser for Humanitarian Assistance and Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs, former World Food Programme (WFP) Gender Adviser & Programme Adviser 1999-2004, Emergency Officer and Head of Sub-Office of WFP tsunami operation, in Aceh 2005 and Senior Adviser for Assistant-Executive Director of UN Women (HQ) 2014-15.

Fri 16 Sept

Videos on Book (VoB) – new format for media enriched e-publishing

Scraps of Hope, with the support from Finnish Cultural Foundation, has developed devise responsive hybrid/media enriched electronic publishing platform Videos on Book (VoB) – one of its first kinds in Finland (http://vob.fi/, soon available in English!).

The first demo version was released in 2015 of Marjaana Jauhola’s peer-reviewed article ‘Scraps of Home’ and the first book ‘Five women, hundred lives’ – focusing on the lived experiences of dissociation – in June 2016.

Digital designer Seija Hirstiö will introduce the VoB platform and tell how the book ’Five women, hundred lives’ came about (dissociation.fi).

Mon 19 Sept

Visual ethnography – collaboration with an ethnographer and digital designer

How to turn ethnographic life history method into documentary films or short videos? How to tackle ethical considerations of documenting lives of non-elites in a complex post-conflict context? Docent, Academy of Finland Research Fellow Marjaana Jauhola and digital designer Seija Hirstiö reflect upon their experience in shooting the Scraps of Hope videos in Indonesia in December 2015.

For more information:

scrapsofhope.fi

Facebook: Scraps of Hope

Marjaana Jauhola, (marjaana.jauhola(at)helsinki.fi, 02941-24228)

Scraps of Hope: Ethnography of Peace in Aceh

To mark the 11th anniversary of the signing of Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on the 15th of August in 2005 in Helsinki in Finland, four new videos were released last week as part of the Scraps of Hope – ethnography of peace in Aceh (2012-16).

Scraps of Hope is urban ethnography of peace, post-disaster and post-conflict reconstruction politics in Aceh, Indonesia by Academy of Finland Research Fellow Marjaana Jauhola – and collaboration with digital designer Seija Hirstiö, funded by Finnish Cultural Foundation and Academy of Finland.

More events will be announced this week!

Follow Scraps of Hope in Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/scrapsofhopeaceh/

Visual portfolio of Scraps of Hope: http://scrapsofhope.fi/aceh

Photo: CMI/Jenni-Justiina Niemi