Edit: on 8 Nov 2016 added first paragraph which was not part of the original written talk but improvised on spot

Keynote on Gender and Conflicts at Power Structures, Conflict Resolution and Social Justice Symposium 13-14 October 2016 EU-India Social Science and Humanities Platform (EqUIP) – please check against delivery.

Before I move on to my prepared talk, I want to add: although I am now located in Gender Studies at the University of Helsinki I have not studied a single module/course of so called Western-campus-taught Gender/Women’s Studies. Rather, the induction to me was Indian feminists and women’s organisations that I got to know when I lived in India 1999-2001. I want to raise this point here in the context of the discussion started at this symposium earlier today of the need to decolonialize academia. I want to encourage you all with this example: we can actually do quite a lot ourselves by reaching out to “alternative archives”. This learning process has been very informative for me and I can see traces of that in my research, and teaching.

—

At this particular moment in time, being one of the European keynote speakers at this event, is particularly painful, but I would also say extremely important: turning the gaze towards Europe, Europeaness and the potential violence that these ideas entail.

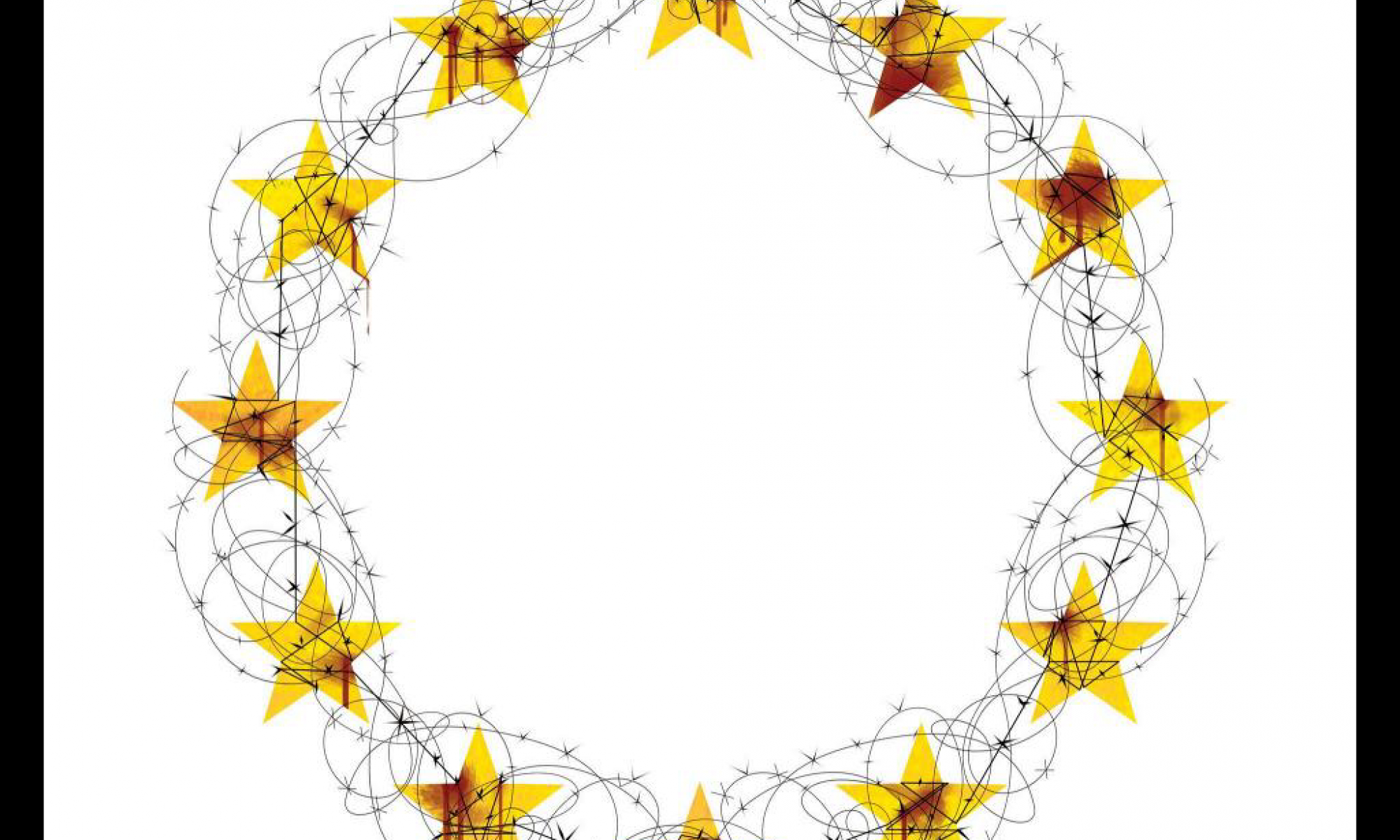

The painfulness stems from the inability of European leaders or European public, along with their global partners to deal humanely the catastrophes that have been unfolding in front of our eyes for years now. Ironically, the European Union (EU) was awarded the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize “for over six decades [having] contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe” and how this contribution is in stark contrast with the realities of post-war European project, such, as

1. Crises that has been unfolding in Syria for too long – the recent broken cessation of hostilities agreement, attacks on humanitarian aid convoys, hospitals and life line services – it truly breaks my heart participating and negotiating the principles and ACTIONS to be taken in the development of the Finnish 3rd National Action Plan on the implementation of UNSCR1325 – when at the same time, so little hope is visible for Syrians in and outside of Syria

2. Building the fortress Europe, and resulting as a crisis of humanity – the inability to address the catastrophe on the shores of the European union in particular related to migration policies and the return to national self-interests and reinforcing the European Union’s external border with a severe humanitarian cost.

3. Gendered Political Economy: Cedaw committee’s reports on Greece in particular, are alarming: the aftershocks of the 2008 financial crises, especially in the Eurozone, that are felt as new structural forms of gender violence: austerity measures that have brought along with them new forms of gender conservatism and discrimination – measures that have been at the heart of the demands of the troika of IMF, European Central Bank and European commission have been at the forefront – making demands to cut social and health services (major employment sector for women) – but also new restrictions to women’s rights such as sexual and reproductive rights as the recent cases from Spain, and Poland, illustrate

4. Growth of populist right wing politics, Islamophobia and racism and violence that takes form – just to give you a few examples from Finland – campaigns to “close borders” and “protect white Finnish women from brown men” entering Finland as asylum seekers from Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and other countries in crises.

5. Sexual politics of peace/post-war reconstruction through images of ‘good and respectable women’: Inability to address history of gendered violence in conflicts internally – I use here 1) the case of “German brides” in Finland, and the demonization of Finnish women who fraternized with German soldiers, and 2) how post-war reconstruction in the aftermath of WWII/Finnish Lapland has meant several decades long oppression of the only indigenous people – Sámi people – in the whole of European Union.

In the words of Skolt Same activist, theatre director Pauliina Feodoroff: Skolt Sáme world ended after the 1930’s. We Skolt Sámi in three post-Second World War countries of Russia, Finland, Norway live in the spatiality and temporality of apocalypse. Hydropower, nuclear weapons, forced displacements of villages in the name of development, mining activity and cultural change accelerated by wars and displacement have been total: fast and extremely fatal, encompassing all spheres of life. Another Sámi feminist scholar Rauna Kuokkanen (Kuokaanen 2007, Knobblock and Kuokkanen 2015) has suggested that indigenizing the Finnish postwar history writing reaquires mourning of loss and victimhood, without which it is impossible to visualize the future and reabuild oneself and reconstruct the debate in Sámi terms: deal with the question of settler colonialism, conflict between indigenous and post-war recovery market economies, and indigenous political agency.

Let’s have a pause here.

Afore mentioned crises are all taking place simultaneously with another set of global agenda making, i.e. the UN Security Council Resolution 1325, and the consequent 7 other resolutions adopted between 2008 and 2015 also known as women/gender, peace and security agenda.

A recent International Affairs journal’s special issue (March 2016) dedicated to the theme made the following observations:

– WPS agenda is not uniform, in theory, concept or practice

– WPS/UNSCR1325 agenda is most successful at a policy document and resolution level – but not as being translated into various fields of ‘practice’

– Although celebrated as a comprehensive agenda to address gendered conflicts, peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction processes, the implementation, and planning for National Action Plans by the member states has been selective: giving stronger focus on violence prevention and protection (from gender and sexual violence) than on women’s participation in peace and security governance.

– Narrowing down the agenda has ambiguous/paranoid political implications: there is a clear need to focus on conflict related sexual violence, however, losing the focus on participation risks losing the critical significance of articulating women as agents of change in conflict and post-conflict environments AS both right-bearers and rights-protectors

– The focus purely on the conflict-related sexual violence closes the feminist scholar’s observation of the ‘continuum of violence’ – in fact, the peace processes, peace settlements can be dangerous fruits for new forms of gendered discrimination in legal, political and economic spheres.

– Special issue editors Laura Shepherd and Paul Kirby make suggestions: an alternative would be to making the links between sexualized violence and participation visible: and in fact pay attention to how sexualized and gender-based violence inhibits women’s (or more widely those subjectification to Gender-based violence) participation in formal and informal politics. Secondly, it would require acknowledgement that WPS agenda cannot be advocated and implemented without more comprehensive focus on reparation and development, connecting protection and prevention of violence to the questions of rule of law, economic, political, social rights and holistic wellbeing

Furthermore,

– Focus on the UNSCR1325, or implementation is on foreign policy oriented, and UNSCR1325 has therefore become a tool for country-branding

– In the case of Finland, this has led into a severe construction of a myth of “achieved gender equality” – that can be experts elsewhere through gender knowhow and expertism – which remains completely unable to tackle domestic intersections of gender with other social inequalities and oppressions, or the aforementioned crises

– in advocating implementation of UNSCR1325 through peace mediation, humanitarian assistance at the same time when the government has in fact cut down its development aid budget, made several revisions that harden the policies towards refugees and asylum seekers and have allowed continuous growth of neo-nazi, racist movements that not only pose verbal but also physical threat to those opposing them.

I suppose the big (research) questions that I have in mind while wanting to juxtapose these parallel phenomena and political processes, is the following:

1. what happens to the feminist and gender theorising and/or activism on peace & conflicts when they become institutionalized into regional, or state-focused foreign policy agenda – that may become handmaidens or essential part of nationalist, populist, and racist agendas?

2. Following from that, is the following question: What new feminist conceptual and analytical tools do we need to study the lack of policy coherence between interior, migration/refugee, humanitarian, development, trade (arms trade in particular), allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the linkages, often silenced, between policy agendas – that have gendered effects.

It is these times that set up a test for Europe, or European states as “promoters of ideas and values” – juxtaposition that is made in comparison to focus on military and economic power. Normative power Europe is in crises, if it cannot deliver the same normative basis of human rights, humanity and principles of wellbeing to people who are being subjected to right-wing politics, guarding and closing borders.

Thirdly, it is necessary to ask the fundamental question of the discriminative threat of the wording in Lisbon Treaty that establishes the aim of the European Union to “to promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples”. Who counts as ’its peoples’? Who is left out from this notion of European well-being? Using sociologist Gurminder Bhambra’s words: ”such social theorists of European crisis fail to address the colonial histories of Europe. This failure enables to dismiss Europe’s postcolonial & multicultural present” (Bhambra 2015)

Finally, these questions, the divide between the “policy talk” and “implementation” and increasing definition of concepts and terminology to serve specific groups and their entitlements in the face of crises that are global, and that require global, not nationalistic solutions. How do we translate them into theoretical-methodological discussions that go beyond ‘discourse’ as texts and speeches and focus on structures, and embodied materiality. What is the real gendered cost of the fortress Europe, or any other attempt to construct post-war/conflict states and identities – and how should we address them?

Non-Linked References

Bhambra, Gurminder K.. 2015. Whither Europe?. Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 18(2), 187-202.

Knobblock, Ina and Kuokkanen,Rauna ‘Decolonizing feminism in the North: a conversation with Rauna Kuokkanen’, NORA—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 23: 4, 2015, pp. 275–81.

Kuokkanen, Rauna ‘Saamelaiset ja kolonialismin vaikutukset nykypäivänä’, in Joel Kuortti, Mikko Lehtonen and Olli Löytty, eds, Kolonialismin jäljet: keskustat, periferiat ja Suomi (Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2007).

Image credits: Cristiano Salgado, Expresso, Portugal