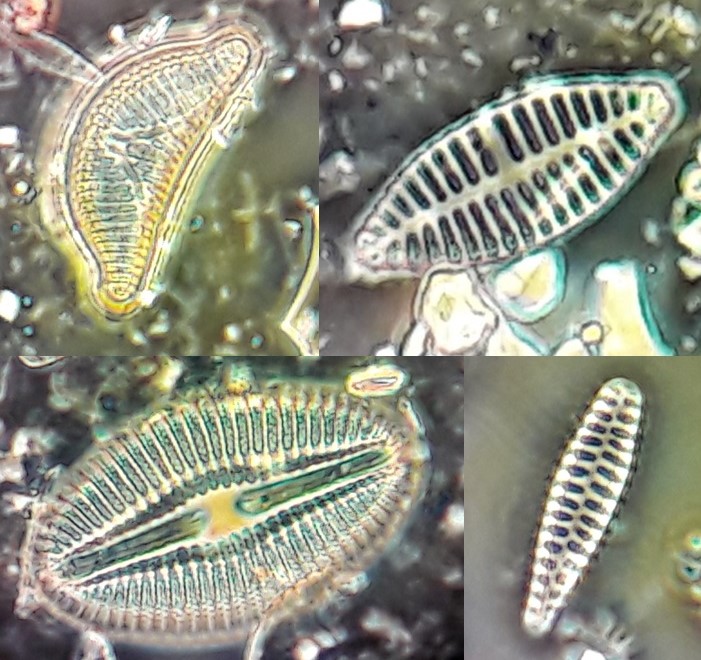

If you take a dive under the surface, you might be surprised to see a lush and vibrant undersea meadow consisting of a diverse range of aquatic plants. As the Baltic Sea is brackish, the biota consists of both marine and freshwater species. This is especially true for aquatic plants, and they are often found growing intermixed, marine seagrasses and freshwater plants side by side.

These aquatic plants form valuable habitats because of many reasons. They produce oxygen, store nutrients and carbon, provide a living environment for many small animals and clarify the surrounding waters. Aquatic plants are found on soft sediments, so where there is enough sunlight reaching the bottom and sandy, muddy or gravelly sediments, there are usually plants around as well. When taking a closer look at these grasses, pondweeds and milfoils, you might see that the different species look quite different. Some of them are tall with ribbon-like leaves and short roots, while others are small with needle or thread-like leaves and long roots. These plant characteristics or traits underlie the effect that these species have on for example, primary production but we do not really know which traits influence production the most. As a plant meadow or community can consist of various species, all with slightly different traits, the functional diversity (i.e. the diversity of traits) can be high.

Different plant species thrive in different environments. Some prefer clearer waters and wave-swept sandy bottoms found in the wind-exposed outer archipelago, whereas others like the calmer waters and muddy sediments found in the sheltered inner archipelago. Therefore, the species and trait composition of plant communities can vary quite a bit depending on if you dive into an undersea meadow in the outer or inner archipelago.

In a recent study, researchers explored which plant traits are important for primary production and whether potential relationships between traits and production change when moving from the outer to the inner archipelago. They visited 30 sites along a wave exposure gradient and used SCUBA diving to sample plant communities and measure different plant traits. The researchers found that one specific trait, plant height, was important for primary production across the archipelago (outer to inner archipelago). This means that no matter what species were present in a community, the taller individuals or species influenced the production to a greater extent. Plants need sunlight to grow and if they grow taller they can access more light and consequently photosynthesize more efficiently.

On the other hand, the study also revealed that the relationship between other traits than plant height and primary production changed in communities when moving from the outer to the inner archipelago. This means that the underlying biological mechanisms that support primary production can vary in different plant meadows and finding out which specific traits are important for production is not always clear-cut.

Not only are lush and vivid undersea meadows beautiful, but these functionally diverse plant communities also play a vital role in the functioning of coastal shallow habitats. With climate change on the rise, it has become ever more so important to recognize that diverse marine habitats such as undersea meadows (whether tall or short!) are important in maintaining ecosystem functioning, increasing the stability of coastal ecosystems and ultimately, contributing to a healthy Baltic Sea.

Read more about the study here: Gustafsson C & Norkko A (2019) Quantifying the importance of functional traits for primary production in aquatic plant communities. J Ecol 107:154-166

Text by Camilla Gustafsson

Photos by Mats Westerbom