Anthropology of randomisation: Randomisation in cross-cultural perspective

RODOLFO MAGGIO

Introduction

In this blog post, “randomisation in cross-cultural perspective” and “anthropology of randomisation” are ideas to play with. As I do so, I am trying to get a concrete feel of the theoretical potential of these ideas, encourage imagination and creativity, and provide an opportunity to work together in a pretend scenario. The anthropology of randomisation does not exist as a subject in its own right, and in that sense, it’s a scenario that is not here yet. But let us go there as if it was, as a first engagement with a new topic, and see what we can find.

© Roger von Oech’s A Whack on the Side of the Head.

What randomisation is and why it matters

Randomisation is a procedure by which a given number of items are arranged randomly, i.e., in such a way as to give each of them the same probability of being selected. It matters, in general, because it provides us with a way of reducing the influence of the observer when evaluating a situation with many variables that are beyond our ability to control. More specifically, it matters for anthropologists: we have always been concerned with the conditions that make knowledge production possible, the interplay between subjective and objective, and the rationality of different modes of knowledge production in various cultures. And yet, randomisation has seldom, if ever, been a subject of anthropological investigation. Hence, with this brief blog post, I would like to initiate a discussion about randomisation from an anthropological perspective.

Structure of the argument

After a very brief review of the anthropological literature that mentions randomisation, but never really engages with the concept in any meaningful depth, I will compare five ways in which different human societies make use of randomisation methods. Such a comparison results in the identification of a common procedure that involves three phases. The three phases also have something in common, i.e. an alternation between two extremes: arbitrariness and non-arbitrariness. Identifying these two extremes leads me to argue that randomisation is a technology of collective anticipation that humans apply to cope methodically and systematically with the cyclical repetition of anxiety and reassurance. In other words, although randomisation is used to make the unpredictability of life and unattainability of knowledge more manageable somehow, it works more because it is a shared practice than because it fully succeeds in attaining knowledge or making life more predictable. Of course, this is a tentative argument, one that is put forward solely to be thoroughly examined, constructively criticised, hopefully validated, and possibly strengthened. The structure of the argument too, with its tidy series of decreasing numbers (5 cases – 3 phases – 2 extremes – 1 function), is intended to make the argument as easy as possible to understand and discuss, not to deny the possibility of a multiplicity of other cases, phases, or functions. Done with the disclaimers, now let’s dive into this fascinating topic!

Literature review

Randomisation can be observed in different cultural contexts. However, it is not the object of much anthropological attention. Searching Google Scholar for “anthropology” and “randomisation”, the results seem to suggest that the relationship between the two is mostly one of antagonism.(1) Despite some attempts at drawing the anthropologists’ attention towards the methodological compatibilities between their own procedures of knowledge production and those that apply some form of randomisation, including my own (Maggio, 2018), these attempts mostly failed “to inspire anthropologists to randomise their observations” (Kelly, 2008: 4).

Randomisation has sometimes become an object of anthropological investigation when it is used in Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT). In these cases, which became increasingly frequent in social science broadly speaking (Brives, 2016: 2), the purpose of the investigation has usually been that of a critical reflection on the negative aspects of RCTs: for RCTs have many “unexamined assumptions” (Mark 2000: 134), “place an increased burden on small non-governmental organisations” (Adams, Craig, & Samen, 2016: 1), and, which I think is the most critical aspect for anthropologists, “present a distinctive particular biopolitical view both of the patient as research subject and of subject populations.”(Adams and McKevitt, 2015: 140).

However, randomisation is far from being solely the product of the biomedical tradition. Much to the contrary, it has been around for millennia. For example, anthropologists have, indirectly, dealt with randomisation every time they analysed divination practices, hardly a subject no anthropologist has ever endeavoured to study (Espírito Santo, 2023). Gambling, obviously, is another object of anthropological attention in which randomisation plays a crucial role, and the anthropological literature is full of ethnographically-informed studies of this very human activity (Pickles, 2016). The recent development of the anthropology of algorithms (Seaver, 2018; Schinkel, 2023) promises to draw increasing anthropological attention to randomisation as a subject of anthropological attention in its own right. For the moment, though, randomisation remains an object of study that anthropologists mostly approach indirectly, i.e. as a component of another object of study, such as the Chinese I-Ching, the Caroline Islands knot divination, the Yoruba Ifa, the Malagasy Sikidi, and the RCTs, which we are going to compare in the following section.

Randomisation in cross-cultural perspective

What do the Chinese I-Ching, the Caroline Islands knot divination, the Yoruba Ifa, the Malagasy Sikidi, and RCTs have in common? I was inspired to ask this question as I took part in the activities of our research team in the research project entitled “Properties of Units and Standards”. In the past two months, we have been reading and discussing Crump’s The Anthropology of Numbers, Asher’s Mathematics Elsewhere, and other publications relevant for the project. Three of the above-mentioned practices that involve the use of a randomizing procedure were mentioned in the first chapter of Asher’s book, whose argument is partly based on a cross-cultural comparison between them. I noticed a commonality between them that Asher did not single out, which I thought worth mentioning instead, and extended the comparison to I-Ching and RCTs. So, what do they all have in common?

The ombiasy performs Sikidi ©haddadToni

5 different methods of randomisation and their commonalities

The brief answer to the above question is that they all have at least one thing in common: randomisation. Randomisation, as mentioned above, is a procedure by which a given number of items are arranged randomly. In RCT, research participants touch the screen of a tablet and are randomly assigned to either a treatment or control group; in Sikidi, the expert in Malagasy divination (ombiasy), “takes a fistful of seeds from his bag and randomly lumps them in four piles” (Ascher, 2002: 16); in Ifa, the diviner “beats the nuts together with both hands and then grasps a handful in his right hand, leaving only one or two nuts in his left hand” (11); in knot divination, “the diviner splits the young leaves of coconut trees into strips, and then they or the client makes a random number of knots in each strip” (8); and in I-Ching the diviner throws three coins, each coin having the same chance of being head or tail, obviously (although there is a tiny chance a coin lands standing on its edge).

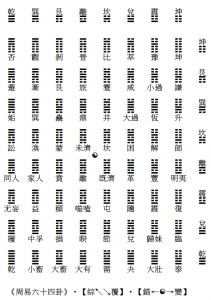

The 8 trigrams and 64 exagrams of I-Ching – Source: Wikimedia commons

What I find fascinating about these randomisation processes is that, despite being governed by chance, they are intended to produce certainty -or, at least, reassurance. People who seek the assistance of a diviner are usually confronted with a question that is practically impossible to answer, because ‘only time will tell’. Is that substantially different from what scientists do when agencies ask them to test the effectiveness of socio-economic policies? Although there is no unfailing method to ensure that the numerical operations will yield objective results, these different technologies of collective anticipation provide a certain degree of confidence by virtue of which they become standard practices in their respective human communities.

The choice of which specific technology to use is, thus, arbitrary: it is a personal choice based on familiarity with Chinese tradition, Caroline Islands tradition, Malagasy tradition, Yoruba, or the biomedical paradigm applied to socio-economic contexts narrated as pathological (such as when RCTs are used to the test the effectiveness of socio-economic policies on in the same way as they are used to test the effectiveness of biochemical therapies). The choice of which specific technology to use is arbitrary, but what fascinates me is how we humans in different cultural contexts try to reduce the level of arbitrariness by means of randomisation. Of course, there are many other ways in which randomisation can be interpreted: as symbolising the idea of relinquishing control to a higher power; as a reflection of the historically specific values, beliefs, and context of a particular culture; and to provide seemingly objective answers and deal with uncertainty.

3-phasic structure of collective anticipation

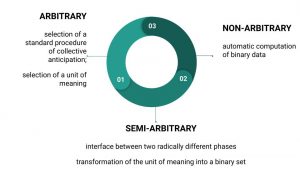

3 phases and 2 extremes

The sense of objectivity is possible because humans use randomisation to channel “data” through the invariable procedures of a binary computation: the two I-Ching trigrams, the two pairs of knotted strings in Caroline Islands, the two columns of Ifa trials, the two sets of Sikidi trials, and the two groups of RCT participants, namely control and treatment group. Once the data are absorbed into the processes of automated computation inherent in each of these technologies, all arbitrariness is suspended, precisely because of the systematic, immutable, and transparent character of their procedures (in that sense, they are considered as standards). It follows that the randomisation process takes place at the interface between a radically arbitrary condition and a radically non-arbitrary condition.

When humans in different contexts make an arbitrary selection of a method or randomisation -or, as defined above, a standard technology of collective anticipation- they arbitrarily choose a non-arbitrary procedure. In so doing, we are making a conscious step into a semi-arbitrary condition (between arbitrary and non-arbitrary) in which our question is translated from a radically arbitrary ‘thing’ (for example, a question about the future) into a radically non-arbitrary ‘thing’ (for example, a couple of trigrams). That question is a unit that we created by arbitrarily selecting some elements of the universe and rejecting others. In the semi-arbitrary phase, our question is broken down into a binary set of items (binary selection of participants, binary set of trigrams, binary set of knots, binary set of seeds, binary set of data). It is no longer arbitrarily formulated, and not yet non-arbitrary. The automatic computation of the binary set of items automatically produces a response. Such a response is as non-arbitrary as the phase in which it was generated, thi third. It is objective.

However, another common feature of these standard technologies of collective anticipation is that they all require an interpretation of the response, an interpretation that is necessarily arbitrary, i.e., subjective. (1) The arbitrary nature of the interpretation of the results makes the results less than objective (or more). Hence, even with these technologies, the search for a definitive answer about the future is eternally unattainable. That is why the non-arbitrary character of the third phase necessarily requires and activates another arbitrary phase. Hence, in conclusion, a third common element between these technologies of collective anticipation is that they are all expressions of our human need to know, the search for an answer that can never be found, and a cyclical repetition of anxiety and temporary reassurance.(2)

A Close-up of the traditional tablet of the Ifa Divination – Source: Wikimedia Commons

The anthropology of randomisation

As mentioned at the beginning of this blog post, although randomisation is not the subject of direct anthropological attention, indirectly it is. To take an example, randomisation plays a major role in some forms of divination, and divination has been one favourite topic of anthropological investigation; if anything, for its relevance in the general debate about human rationality (Lévy-Bruhl, 1938; Eliade, 2022). After all, “All known peoples on earth have practised some form of divination”, as Tedlock wrote (2001: 189). That seems to be a good reason to develop a direct form of anthropological attention for randomisation, rather than an indirect one. However, is randomisation really a core component of some forms of divination? If that was not the case, maybe it is not worth placing it at the centre stage of our attention. However, maybe it is.

Divination is not only randomisation

Diviners do not necessarily make use of the kind of sortition that we can, for all intents and purposes, describe as randomisation. Divination is a much wider category that encompasses other technologies. In addition to forecasting, divination can be diagnostic and interventionist, “in the sense of changing the receptor’s destiny” (Espiritu-Santo 2023). It might even not involve any technology at all: it can also take the form of inspiration that does not seem to be predicated upon any learned, or learnable, technique. This is the classic distinction that Cicero drew between Divinatio Naturalis and Divinatio Artificialis (Cicero, De Divinatione). Arguably, the 5 forms of divination mentioned above fall within the latter category, for they involve relatively advanced knowledge and manipulation of technical objects.

The advanced nature of this technical knowledge well serves an argument against the supposed absence of rationality in divination practices, although not only that. Regardless of divination being taken in its “natural” or “artificial” form, it can be explained as a rational means of exploring and/or explaining reality, but also as a way of making reality, of world-making (Matthews, 2021), to use a term that ontologically-oriented anthropologists often keep in their conceptual toolkit (cf. Bessire & Bond, 2014: 441). Both forms are, thus, equally valuable and potentially useful for an argument about different forms of knowledge production. However, the “artificial” form of divination is mostly relevant here, for randomisation is not the kind of practice that can be expected to be incorporated in spontaneous forms of divination that require no training or advanced manipulation of special tools.

This is a major distinction to draw, for several reasons. A focus on tools means a de-focus on the body, in this case. Trigrams, knots, seeds, bones, shells and tea leaves, all lend themselves to be used in the randomisation process, for they are separated from the individual bodies of the diviner and, as a consequence, eliminate or limit the influence of their individual subjectivity. However, it is interesting to note that the body of the expert is, nevertheless, involved in the sorting phase, at least to some extent. More specifically, the hands. As mentioned above: research participants touch the screen of a tablet, the ombiasy takes a fistful of seeds; the Ifa diviner “beats the nuts together with both hands and then grasps a handful in his right hand, leaving only one or two nuts in his left hand” (11); and in knot divination, “the diviner splits the young leaves of coconut trees into strips, and then they or the client makes a random number of knots in each strip” (8); and in I-Ching the expert throws three coins. These are all different ways of randomising.

In this sense, “artificial” forms of divination also involve the body, although not to the same extent as other, more “natural” forms of divination. Somehow, these relatively more body-dependent forms of divination attracted the interests of anthropologists more than techniques of divination that mostly rely on technical objects. One might well argue the opposite, for the literature is full of studies of “artificial” divination, such as those by Joseph Needham. However, if that was really the case, why the expression “anthropology of randomisation” has never been used before? It seems to be due to the relatively less attention anthropologists pay to the technical aspects of divination. Or can it just be a random turn of events?

Random anthropology

This is a question that I have been pondering upon, recently, as a result of drawing the above, kind of “Frazerian-style … uncontrolled comparison” (Sahlins, 2011: 2) between the components of different “techniques of collective anticipation”, as I have been, tentatively, referring to the various practices that incorporate a randomising method.(3) This comparison belongs to a series of, rather random really, thoughts that I have been trying to connect to the theme of the project “Properties of Units and Standards”. Hence, this short blog post too is, in a tong-in-cheek kind of fashion, a sort of random anthropology: it is a logos that moves randomly among anthropological objects such as divination, gambling, and other practices that, explicitly or not, include some forms of randomisation; and asks: does the absence of an anthropological interest towards randomisation mean that randomisation indeed ought not to be of interest for anthropologists?

If that were the case, such a lack of anthropological saliency would be a rather unique case. It is, indeed, very hard to come up with an object of study that, especially nowadays, ought not to be of interest to anthropologists. Anthropologists study anything, including objects that require a considerable effort of imagination, not to say of technical expertise, to consider as worthy of anthropological interest, such as metagenomics labs (Raffaetà, 2023), biology textbooks (Martin 1991), or dogs’ dreams (Kohn, 2007). If these have become objects of anthropological study, shouldn’t randomisation be an object of study too?

And, if the answer is that, yes, randomisation ought to be an object of anthropological study, what would such a study look like? Presumably, at this stage, that would be a novel theoretical study based on the secondary analysis of ethnographic accounts of randomisation practices observed in different parts of the world. In other words, that would be the kind of comparative analysis presented in this blog post as a tentative way to kick off the discussion, but in a much more methodologically rigorous and literature-rich fashion. Hopefully, this kind of theoretical discussion will produce the kind of conceptual tools that one could use to compare and differentiate the characteristics of different forms of randomisation in different cultures. Or maybe not? Maybe it would just be a random exercise of sterile intellectualism that will lead nowhere. It is possible, and I seriously considered that before I started to write. But, what if, by looking at randomisation from an anthropological perspective, we discover something of value? This seems to be a sufficient reason to try and explore randomisation cross-culturally.

After all, it is estimated that a large proportion of all scientific discoveries are mostly random.

Notes

- I discussed why this might be the case, and why this antagonism might be unwarranted, in Maggio, Rodolfo. 2018. Experimental ethnographies of early intervention: a new ‘gold standard’? Narrare i gruppi. 13(2): 275-298.

- Although it might be argued that, from an ontological perspective, the first phase is non-arbitrary and the third phase is arbitrary, that does not seem to alter the fundamental structure of the model, for the two phases are invariably mediated by randomisation.

- The expression “techniques of collective anticipation” has been used in a publication by Olivier Servais (2018), although it seems to be unrelated to randomisation and even divination more broadly.

References

Adams, M., & McKevitt, C. (2015). Configuring the patient as clinical research subject in the UK national health service. Anthropology & Medicine, 22(2), 138-148.

Ascher, M. (2002). Mathematics elsewhere: An exploration of ideas across cultures. Princeton University Press.

Crump, T. (1992). The anthropology of numbers (No. 70). Cambridge University Press.

Eliade, M. (2022). Patterns in comparative religion. U of Nebraska Press.

Espírito Santo, Diana. (2019) 2023. “Divination”. In The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Felix Stein. Facsimile of the first edition in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Online: http://doi.org/10.29164/19divination

Kelly, A. (2008). Pragmatic evidence and the politics of everyday practice. How do we know, 97-117.

Kohn, E. (2007). How dogs dream: Amazonian natures and the politics of transspecies engagement. American ethnologist, 34(1), 3-24.

Lévy-Bruhl, L. (1938). L’expérience mystique et les symboles. Félix Alcan.

Matthews, W. (2021). Cosmic coherence: a cognitive anthropology through Chinese divination (Vol. 13). Berghahn Books.

Maggio, R. 2018. Experimental ethnographies of early intervention: a new ‘gold standard’? Narrare i gruppi. 13(2): 275-298.

Marks, H. M., & Bouillot, F. (1999). La médecine des preuves: histoire et anthropologie des essais cliniques (1900-1990). (No Title).

Martin, E. (1991). The egg and the sperm: How science has constructed a romance based on stereotypical male-female roles. Signs: journal of women in culture and society, 16(3), 485-501.

Raffaetà, R. (2023). Metagenomic futures. How metagenomic is reconfiguring health and what it means to be human.

Seaver, N. (2018). What should an anthropology of algorithms do?. Cultural anthropology, 33(3), 375-385.

Servais, O. (2018). Deviner son prédateur, trouver sa proie: Des pratiques cynégétiques et divinatoires dans le jeu vidéo World of Warcraft. Anthropologie et Sociétés, 42(2), 307-329.

Sahlins, M. (2011). What kinship is (part one). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 17(1), 2-19.

Schinkel, W. (2023). Steps to an Ecology of Algorithms. Annual Review of Anthropology, 52.

Tedlock, B. (2001). Divination as a way of knowing: Embodiment, visualisation, narrative, and interpretation. Folklore, 112(2), 189-197.