Jakob Grandin, Sanna Gunnarsson and Sara Andersson

Centre for Environment and Development Studies, CEMUS

Uppsala Centre for Sustainable Development, CSD Uppsala

Uppsala University

Once I found inside a forest, an ax cut down in the ground all the way to the hammer.

It was as if someone there had wanted to cleave the whole earth in two pieces in a single stroke.

The will had not been lacking, but the handle had broken off.

Harry Martinson, 1958 (translated by Jakob Grandin)

Courses in sustainable development often introduce and discuss daunting, complex, and urgent problems that have no simple solutions. For us, this implies a special responsibility when education for sustainable development is designed. To the best of our knowledge, none of our students has been so frustrated after a course at CEMUS that they have attempted to cleave the Earth in two. At the same time, many have definitely left the courses overwhelmed as they feel responsible personally to move the whole world to sustainability. A partial explanation for this sometimes disheartening result is that sustainability problems are often framed in abstract, global ways that obscure responsibility and impede local agency (Head & Gibson, 2012; Hulme, 2010). But it is just as problematic that the discourse on sustainability in both education and society has a predominant focus on problems, and that solutions, opportunities, visions and pathways are not as widely examined. The discussion in the Helsinki principles on action competence, transgressing boundaries and developing an “ability to create new possibilities and solutions where none formerly seemed to exist” is hence urgently needed.

To live and act sustainably in this world calls for adequate tools, but also skills to use these tools with grace so that they do not break or cause harm. Therefore, we created a five week long course with the title “Processes for Change: Leadership, Organization and Communication”. While the course has a solid foundation in social theories on change and transformation, our approach was deliberatively normative: to explore the practical potential of various theories for change, to learn from successful change movements, to co-create a toolbox for change and – not the least – to create a space for our students to develop their own capacities as change leaders. Created in 2012, the course was significantly reimagined 2014–2016 as a result of conversations in the ActSHEN group.

Which students are invited to co-design their education?

Since the beginning with Humanity and Nature in 1992, CEMUS courses have been student run in the sense that students are hired as course coordinators to design, facilitate and administrate the education. This has led to courses based on active, critical and pluralistic pedagogies that resonate well with the Helsinki principles on pedagogy and learning outcomes. The “Processes for Change: Leadership, Organization and Communication” course of 2012 was no exception: designed around seminars, workshops and a group projects, where students played an important role in co-creating an understanding of what theoretically founded and practically oriented processes and tools for change might imply. However, early feedback from our ActSHEN colleagues also highlighted significant room for further innovation. A pivotal question that came up in the conversations leading up to the Helsinki principles was: which students do, in fact, actively participate in their education, and which students are invited to co-design their education? In the CEMUS model, the course coordinators have the most to say. The course content and the pedagogy is mostly decided before the course starts and there is usually only limited space for the students that actually take the course to influence its core content.

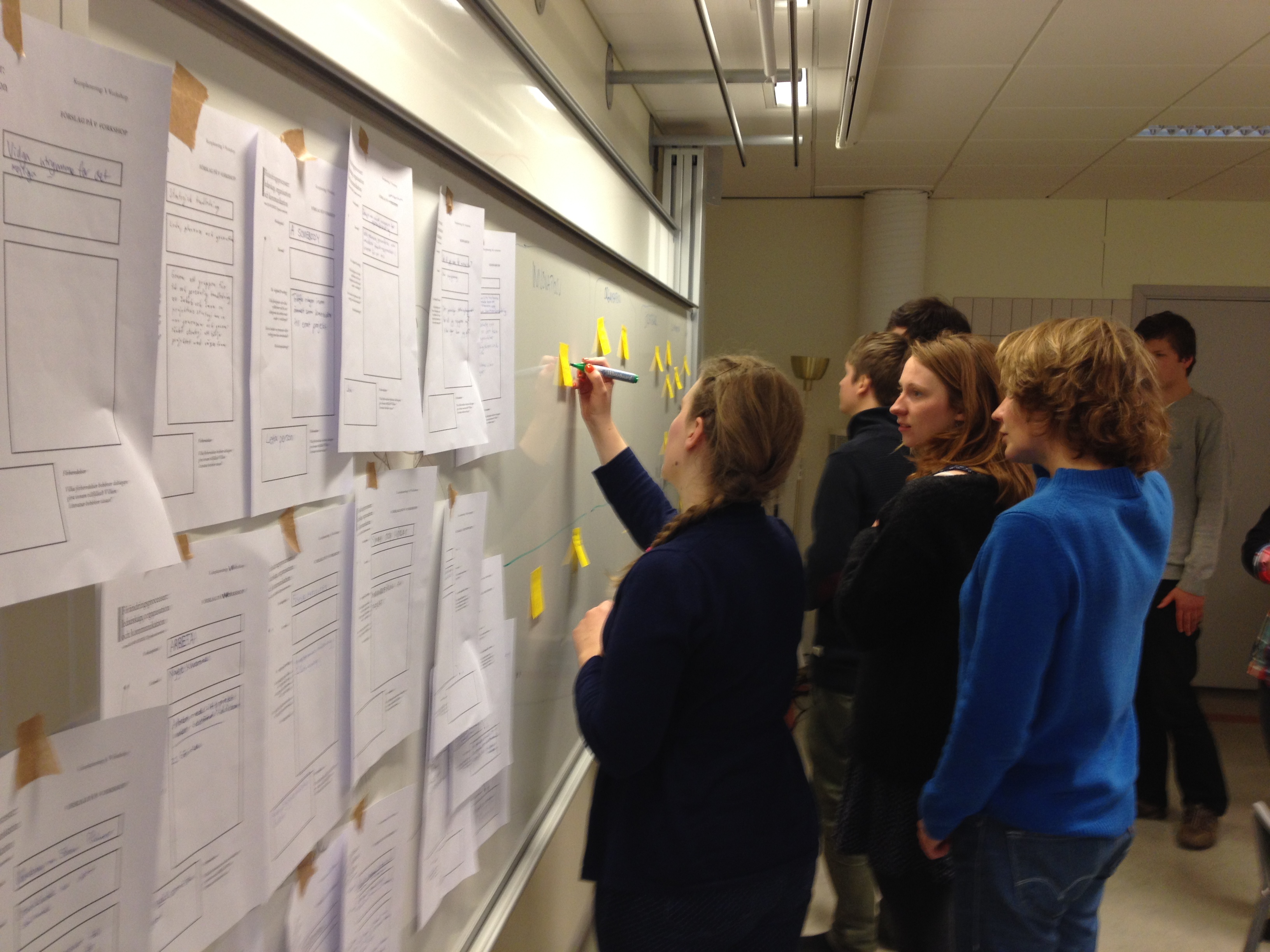

Taking on this challenge from the ActSHEN group, we decided to radically redesign the course 2014–2016. We wanted to involve the students taking the course in decisions regarding content, assessment and pedagogy. We went for an approach that was somewhere at the middle of the road. As course coordinators, we decided about fifty percent of the course content and assessment before the course started. The other fifty percent was up for the students to decide. The course began with an intensive week where social theory, historical examples and practical approaches to social change was discussed. As conclusion of that week, we facilitated a 3 hour workshop where the students were invited to co-design the rest of the course using the learning outcomes and constructive alignment theory (which calls for the alignment of learning outcomes, assessment and teaching in a course) as guiding principles for what was to be included and what was not. Students brainstormed what types of theoretical content and practical tools they wanted to explore and learn more about in the course – and also discussed and suggested how they wanted to be assessed. To get them started, we provided them with a “menu” of different possible course modules that they build on and redefine – but the students were encouraged to bring completely new ideas to the table as well. Students were then asked to write first drafts of assignments (in bullet points), define content of seminars and workshops, prioritize between different ideas, and then, finally, co-create a course schedule that was adopted in consensus. The outcomes from the workshop were processed by the course coordinators and integrated into the course.

Pluralism, iteration and lessons from arts education

We will soon discuss the outcomes of this workshop, how it affected the course and what our students thought about it, but let us first briefly touch upon a second area of inspiration from the ActSHEN process. In the “Processes for Change: Leadership, Organization and Communication” course, we built on a critical and pluralistic approach to learning in order to “enlarge the space of the possible” (Osberg, 2009) and unlock the opportunities and choices available in different epistemological framings (Healy, 2003). We were inspired by J. K. Gibson-Graham’s (2008, p. 615) assertion that “to change our understanding is to change the world, in small and sometimes major ways” and built on her three “performative practices” that may open up “other worlds”: ontological reframing, re-reading for possibility, and creativity. At the same time, we kept asking ourselves how to actually translate these somewhat abstract ideas into pedagogy and build them into the learning process. We discovered a possible way forward when one of us visited the Iceland Academy of the Arts as part of an ActSHEN meeting. Here, the arts, design and architecture education was based on the “iterative processes of continuous learning and refinement of concepts and ideas” that is now enshrined in the Helsinki principles. Could we use a similar process for our course on leadership and strategies for change?

Inspired by the education at the Iceland Academy of the Arts, we created an iterative project process, parallel to the student co-designed sessions described above. Students developed change projects to be run throughout the semester. To facilitate the process, students were asked to critically assess their theories of change, strategic plans, and project aims in a series of design critique sessions (“crits”). The aim of these sessions was to involve the students in continually giving and receiving critical feedback from each other, and to continually learn and improve both their understanding of their world and the strategies used to create change. It turned out that our students found this process overly complex. They considered both the crits and the iterative project process stressful. As facilitators, however, we observed how students in the crits took roles both as critical interrogators and creative problem solvers and that these continuous meetings did improve the quality of the projects. We are therefore still convinced that education for sustainable development in general has a lot to learn from how arts and design education attempts to develop students’ creative capacities and explore divergent possibilities. At the same time, we admit that it takes significant time and effort from both students and facilitators to understand how to make the most out of these pedagogies, and that they require proper translation to work in new contexts.

Conclusions: From self-deceptive simulations to true participation

Looking back at the course, we see that the process of opening up for co-designing of the course together with students had both strengths and weaknesses. Perhaps most importantly, the workshop where the course was co-designed turned out to be an important occasion in the course that was highly regarded by the students. The workshop provided a space where students were encouraged to, and supported in, reflecting on different learning-styles, pedagogy and how to balance both content and form in the remaining weeks of the course. Some students also noted that the process helped them develop a more reflective approach to their learning: “It was fun to think in terms of ‘learning outcomes’” as one student put it in the course evaluation. The course evaluations also indicated that students felt increased ownership of their learning process. One student wrote: “Being an active part of the process made participation more motivated” Another quote: “I can’t fully grasp that I have been a part in deciding [the content of the course]. [It] feels almost surreal.”

On a more critical note, we also encountered challenges with opening up the course for co-creation. For instance, some important content from the course of previous years was lost in the process. In the course evaluations, one student noted: “It was interesting, but if we had not been a part of the planning, the workshops and seminars might have been more connected to the literature and I think that would have been good for the learning” Students are, naturally, conditioned by what they have experienced previously in their education. This resulted in a repetition of themes that had already been discussed in the course, rather than an exploration of more novel issues. This in turn raises the question of how the process of co-designing a course impacts the content of the same, and whether the content may be compromised by a co-designing process. A student (who admittedly did not attend the workshop) also raised concerns that “students that are more vocal might influence the course planning more than those that are not as comfortable with arguing for their point of view”.

Læssøe (2010) discusses the risk that participation in education becomes a “self-deceptive simulation” that reinforces dominant discourses and power relations in society rather than challenges them. This is a challenge that we need to take seriously when we invite students as co-creators and co-designers of education. It is therefore essential to prepare and design the process of co-design in a way that allows students to participate in a real and meaningful way, and which gives room for creative, novel, and divergent ideas.

So in the end, this brings us back to Harry Martinson’s poem that introduced this essay. As the enthusiasm and initiative in the ActSHEN project has shown, the will to involve students as co-creators in education is certainly not lacking. That achieving true participation is difficult does not mean that we should lower our ambition. But it does mean that we need to develop appropriate tools and methodologies for action for sustainability in higher education, and use them in sound ways.

References

Gibson-Graham, J.-K. (2008). Diverse economies: performative practices for `other worlds’. Progress in Human Geography, 32(5), 613-632. http://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508090821

Head, L., & Gibson, C. (2012). Becoming differently modern: Geographic contributions to a generative climate politics. Progress in Human Geography, 36(6), 699-714. http://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512438162

Healy, S. (2003). Epistemological pluralism and the “politics of choice.” Futures, 35(7), 689-701. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(03)00022-3

Hulme, M. (2010). Problems with making and governing global kinds of knowledge. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 558-564. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.005

Læssøe, J. (2010). Education for sustainable development, participation and socio‐cultural change. Environmental Education Research, 16(1), 39-57. http://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504016

Osberg, D. (2009). “Enlarging the space of the possible” around what it means to educate and be educated. Complicity: an International Journal of Complexity and Education, 6(1).