By Florencia Quesada Avendaño (Core Fellow, HCAS)

It was a blue-sky day at the beginning of February in Guatemala City, our last day of fieldwork in the community of Arzú (Photo 1) – named after Alvaro Arzú, former Guatemala City mayor and former president of Guatemala (1996–2000). Arzú is a slum located in a high-risk area in zone 18, which is the largest and most populous zone in the northern part of the city. The municipality of Guatemala is divided into 22 zones, with the greatest number of precarious settlements being located in zones 3, 7 and 18 (SEGEPLAN 2015).

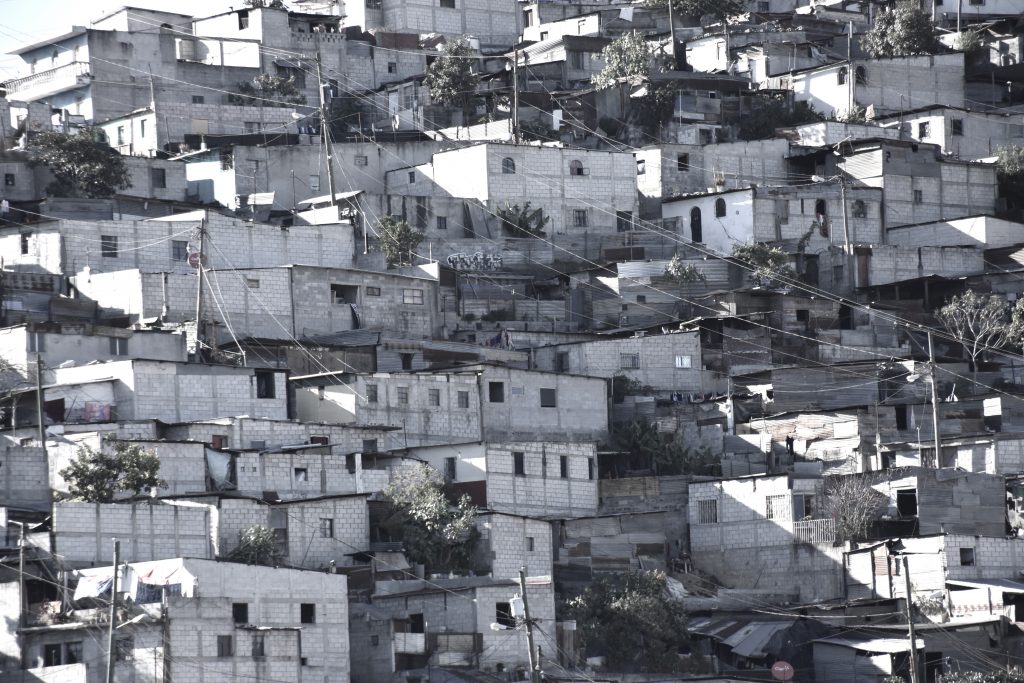

Photo 1: Panoramic view from the community of Arzú (Photo: Florencia Quesada) Many slums in Guatemala City are built in vulnerable places, like the ravines that surround the capital.

(Photo: Florencia Quesada) Many slums in Guatemala City are built in vulnerable places, like the ravines that surround the capital.

The fieldwork, conducted in cooperation with our local partners – a local NGO called “Perpendicular” – was both challenging and difficult.[*] The main goal was to conduct interviews in precarious settlements about the daily life, struggles, problems, organisation and perceptions of the inhabitants with respect to violence, insecurity and environmental risks. Local contacts with community leaders and the previous and recent experiences of our local partners working in the communities of Arzú and 5 de noviembre opened the doors rather quickly to a complex urban space.

Guatemala City is the largest city and capital in the Central American Isthmus. Its metropolitan area has a population of 2.8 million inhabitants, distributed over 2189 km2 (SEGEPLAN 2015). At the same time, the metropolitan area accounts for the largest concentration of poor people by square metre in the country, with an estimated 412 precarious settlements (SEGEPLAN 2015).

In these unequal and unjust urban spaces, insecurity and fear are the daily bread of the urban poor especially in Guatemala City. Nevertheless, nobody escapes from violence in the country. Guatemala is one of the most unequal countries in the world. This extreme social urban segregation, characteristic of Latin America’s urban landscape, is well represented in zone 18. A high percentage of the population lives in poverty and extreme poverty. Some of the slums are located in high-risk areas prone to landslides, flooding and earthquakes. Precarious settlements are characterised by self-built housing, with very limited and insufficient public services and infrastructure (Photo 2). Over the years, and through the organisation of the community, the limited aid of the municipality, the State and NGOs like TECHO, some of these precarious settlements have improved their living conditions and services, but always still working from a marginal and excluded position.

Photo 2: Precarious settlements built in high-risk areas, Guatemala City (Photo: Florencia Quesada)

(Photo: Florencia Quesada)

As part of the same complex urban panorama, these communities are also very insecure and violent. Certain parts of zone 18 have the reputation of being the most dangerous in the city. Especially in the lower-class areas, youth gangs like ‘Mara 18’ (18th Street gang) and other minor gangs control territory by extorting money from local businesses and public buses and taxis. Doubly stigmatised because of its poverty and the bad reputation of zone 18, daily life in both communities is a day-to-day struggle, as was evident in all of the interviews.

Paradoxically, the violence has been normalised: it is now perceived as a central and inevitable part of society. One of the reasons for the trivialisation of violence has to do with being bombarded with sensationalist TV news on a daily basis. Shootings, homicides, kidnappings, assaults and rapes dominate media; they are presented as the norm, the tragic reality that feeds paranoia – a big business for some – exacerbating those imaginaries of fear. Most of the interviewees highlighted how insecure and dangerous the city was by referencing their first-hand experiences, but they especially mentioned their perceptions being influenced by the television news.

In a post-war society such as Guatemala (after a civil war that lasted for thirty-six years), the expressions of violence originate from and overlap with a multiplicity of reasons, like State violence, high rates of impunity and corruption, social and economic exclusion of broad segments of the society, to name just a few. Citizens’ sense of insecurity is closely related to the failure of the State to ensure the basic needs and rights of its citizens and to offer security to a majority of the population. Violence is a direct expression of exclusion and inequality and has a devastating impact on the daily life of the urban poor.

One of the interviewees, a blacksmith in his late 30s, is at the same time a good and sad example of such structural and daily violence. His self-built house is located on a steep hillside. To reach his dwelling at the bottom of the hill, you must first descend the concrete stairs built by the community. Ironically, he earns his living by selling iron fences for the protection of such dwellings. Three years ago, he was shot by a member of Mara 18, the gang that rules the area. The gang member came to recruit his cousin by force, who was working at the time in the man’s workshop. His cousin escaped, he was not so fortunate. The young marero turned to him and started shooting without mercy: four bullets hit him in the arms (two in each arm). While trying to escape, the last one hit his spinal cord; the bullet is still there. He can no longer walk and is condemned to life in a wheelchair. Now his life is limited to a 5×5 space, disabled, without any support or economic aid from the State; his possibilities are quite limited. His extended family – parents, wife and two adult sons – are the only support he has. He seldom goes out of the house since the logistics of going up the steep hill are complex (Photo 3). He has diabetes, which affects his eyesight. His steady gaze is gloomy.

Photo 3: Looking down the hill in the community of Arzú  (Photo: Florencia Quesada)

(Photo: Florencia Quesada)

Nevertheless, although the gangs are directly associated with high levels of urban violence, they are not the only ones to blame in the multifaceted panorama of urban violence. Gangs are easy scapegoats for the State, helping it to avoid facing the main causes of violence in the region, such as poverty, unemployment, inequality, exclusion and the lack of possibilities to earn a decent living. Through this research project, we aim to understand and analyse the dynamics of these complex processes of violence and environmental risks in order to rethink alternatives and offer possibilities for these fragile urban communities, which only keep multiplying in Central American cities (Photo 4).

Photo 4: Precarious settlements in Guatemala City (Photo: Florencia Quesada)

(Photo: Florencia Quesada)

[*]This research is part of a project funded by the Academy of Finland: ‘Fragile cities in the global South: societal security, environmental vulnerability and representative justice’, coordinated by Anja Nygren. The project aims to analyse the roles of new city-authority coalitions, organised civil-society groups and informal network-actors engaged in seeking new ways to manage societal insecurity, environmental vulnerability and representative justice in the fragile cities of the global South. Guatemala City is one of the case studies focused on violence and environmental risks, along with Villahermosa in México, Bogotá in Colombia and Calcutta in India.