By Lois Watt

The terms reciprocity, collaboration and inclusion are being used with increasing frequency in the discourse on research ethics. Yet, the practicalities of implementing such ideas can quickly become muddled. For many newly starting ethnographers, the question of how one should approach these ethical conundrums can become enervating. But what do the seasoned pros have to say? I sat down with three HCAS fellows (Cris Shore, Nina Öhman, Wasiq Silan) to discuss what aspiring to such changing research ideals means for them and how they position these ideals against their own ethnographic research. The result is an interesting intersection of different perspectives, one which exemplifies the lack of clear answers to many of the ethical questions that we are facing today.

Online/Onsite?

Picture this. July 7th, 2022. It is officially a ‘post’ pandemic time, and we are only just warming up to the outside world after two years of social distance and virtual connections. I have just sat down, coffee in hand, at my laptop, which is opened to the livestream of an online seminar series hosted by the Royal Anthropological Institute (RAI), entitled Before and After Malinowski: Alternative Views on the History of Anthropology. This year marks a full century since Bronisław Malinowski’s canonical work Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922) was published. Malinowski is often cited as being the father of British anthropology, having been largely responsible for cementing functionalism within British anthropological thought, and – with Argonauts in particular – of leaving a huge mark on the legacy of how anthropologists should go about doing immersive, long-term study in ‘peripheral’ places, otherwise known as ethnography.

Contact print made from the original Malinowski photo-negatives of the Trobriand Islands, undated. Bronislaw Malinowski Papers (MS 19). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

Yet, here we are – half-listening as we fold laundry and daydream – at ‘Home’: after two years of mandatory isolation. Many of us who use ethnography as a research tool have struggled to ‘go’ anywhere. Indeed, many scholars who use ethnography are increasingly turning inward. In epistemological textbooks, you frequently spot key phrases like multi-sited, ‘at Home’ and digital ethnographies. So, when listening to these scholars discuss what makes a text canonical, one cannot help but reflect on how much ethnography has changed since its early days, under the influence of figures like Malinowski.

Today, ethnographic methods have extended beyond anthropology to include a host of different disciplines. Yet, the principle often remains the same: you should be there in order to get a sense of what is really going on.

Photo: Andrea Piacquadio, pexels.com

This reflection is also linked to the question of why we consider texts like Argonauts to be disciplinary cornerstones. In the case of Malinowski, one cannot escape the dark past that lingers between the lines of his published works. In his posthumously published field diaries, his observations and assessments become more convoluted. As such, the legacy of ethnography often gives rise to a certain amount of unease for researchers. Yet, we still admire and acknowledge the feats of many early anthropologists despite their ties to the colonial project and orientalist gaze (Said, 1979).

Over time, notes of resistance to the legacy of these early ethnographers have become more vocal (Smith, 1999; DeCastro, 1998). In this century, the rise of indigenous studies, the various anthropological ‘turns’ (literary, critical and ontological) as well as the advocacy for anthropologists to do multi-sited ethnographies has reshaped our relationship to ethnography as a tool and to our participants. These critical voices have raised a pivotal question: Who has the right to study whom?

The answer is often not at all clear. Ethnographers must grapple with such demands in their own way. But how have scholars finessed their way through this moral maze to continue doing fruitful ethnographic research?

Nina Öhman, Wasiq Silan and Cris Shore (left to right)

To try and gain some clarity on the matter, I interviewed three current HCAS fellows, anthropologist Cris Shore, ethnomusicologist Nina Öhman and Wasiq Silan, a scholar of indigenous studies, each of whom actively uses ethnographic methodologies. Despite similarities in their methodologies, the way in which they execute the methods varies greatly. I became curious: How do they navigate this troubled terrain, and how do they relate to ethnography?

Cris: I say that I’m agnostic about ethnography. It is supposedly the crown jewel of anthropology’s tool kit. Yet we have created a bit of a fetish around ethnography, and it’s become something that defines what anthropologists do and what distinguishes them from other disciplines. People say that ‘We [anthropologists] do ethnography! We do fieldwork! We do long-term fieldwork and participant observation!’ But my own feeling about that is that it’s only one of many methods, and it’s not the be all and end all. I don’t buy into the idea that there’s an ontological imperative to always ‘be there’ because I see the world very much in terms of the wider, bigger forces that shape local events – history, politics, economics … these are important as well. To put it simply, the ‘truth’ (if you can use that word anymore) does not necessarily lie at the level of empirical reality. If you confine or conflate anthropology with ethnography, then you’re not going to get the bigger picture. And if anthropology is defined by its method, then it means that certain key areas, the areas that I love to research, would be out-of-bounds because you could only really do anthropology in the areas where you could do direct participatory observational fieldwork ethnography. I can’t pitch my tent in the board room of IBM!

Cris Shore is a professor of social anthropology at Goldsmiths University, in London. His current work is concerned with shifting forms of university management, tentatively titled Metricised Management, Market-Making and University Futures. In dealing with ‘elite’ institutions, Cris frames his work as a form of studying ‘Up’. Unlike many of the classic ethnographers, who can safely be said to have studied ‘Down’, Cris reflects on how he is often in a more marginalised position when entering the field. In that way, his research context is different from that of Nina Öhman, who works with various musical communities, and Wasiq Silan, who works with more disadvantaged groups.

Nina Öhman is an ethnomusicologist who studies women’s roles in music cultures. She holds a particular specialisation in American popular music – with her most recent work focusing on African American gospel music in a project entitled Audible Subversion: African American women singers and gospel vocal expression. This is what she had to say about her relationship with ethnography.

Nina: Ethnography is central to my work. Since I am an ethnomusicologist, for me ethnographic methods are very important, as well as the study of musical sound. In my work these approaches are closely connected, along with historical research. One can of course listen to music and analyse music digitally, which I do as well, but I think it is crucial to speak with people who are making music or engage with music in other ways and take what they say seriously. Therefore, ethnography has a real value to science.

But whilst there is this value, one cannot escape the ‘troubled past’ that ethnography holds. Thinking of, for example, these famous classic monographs. As someone who actively uses ethnographic methodologies, there is constant reflection and thinking about the ethical implications of doing ethnographic research, as we [ethnographers] are learning all the time. As such, there are blind spots everyone is likely to have when we are in the field, and at least by acknowledging the limits of one’s knowledge, we can work through these, especially through reflecting and learning.

Nina’s research interests are centred around the role of music – its expression, performance, significance and history. In that way, Nina enters a field in which she is not the ‘expert’ in the sense that she is working with musicians who are embedded within the sound that she is studying. As such, she stresses the importance of listening to the expertise and knowledge of her research participants. This collaborative effort marks a shift from the classical ethnographers, who – one could say – tended to meta-analyse culturally situated behaviours against Western moralities. This focus on collaboration, however, is pushed even further in Wasiq Silan’s work.

In coming from an indigenous studies perspective, Wasiq Silan – a Tayal scholar from the Mstaranan river valley in the northern region of Taiwan – has centred her academic interests on her home country of Taiwan and has worked with the Tayal people on several different themes. Wasiq’s latest work is entitled Care in Relationships: Re-centring Indigenous Older Women’s Voices, an interdisciplinary, multi-sited project concerned with reframing the way in which being elderly is understood through engaging with alternative ways of perceiving ageing and care in Tayal indigenous and other cultural contexts. With a background in political science, Wasiq initially felt invigorated when employing a critical ethnography approach. However, despite sharing certain societal concerns, she found indigenous studies to be the most inclusive discipline in terms of epistemology. Within indigenous studies, the space to radically re-think, adapt and decolonise research in order to really listen to the voices of indigenous people and ontologies is far greater than it is in other disciplines, such as anthropology.

Wasiq: I personally find ethnography very refreshing! And I think that is because I was trained in political science. So, [during my training] there was this tension in the application of these grand theories to local events. In many ways, I think a lot of the topics that ethnographers care about resonate with indigenous researchers. It’s just that there’s a way about doing things which is different. There are a lot of Western scientific ontologies that we [indigenous studies scholars] criticise. However, I think ethnography could be an exception because ethnographers are doing something that they think is critical, so we can work together in one way or another. In that sense, there are other methodologies that are further away, like those in political science.

Despite remaining critical of ethnography, Wasiq points to the potential for ethnographic methodologies to adopt alternative ontological perspectives when compared to the methods used in other mainstream academic disciplines. Indeed, all three scholars emphasised a sense of the inherent flexibility of ethnography – regarding its ability to be moulded to fit vastly different research contexts. The terms research participants and collaboration have already been mentioned. These terms give an example of how ethnography has changed over the years: rather than referring to the people who take part in a study as ‘informants’ (as was once common), researchers are increasingly using the word ‘participant’. This shift in discourse signals a recognition of agency for those involved in academic research, an important point that Cris, Nina and Wasiq all touched upon, albeit by referencing different perspectives. In pressing on this point, I wanted to address the potential conflicts that may arise from this recognition of agency in ethnographic fieldwork.

Collaboration or Complicity?

Question: A strong case has been made to further include ethnographic participants as research collaborators. However, can this approach be adopted in all research contexts? Furthermore, how can we, as researchers, negotiate alternative ontologies in cases where one’s own positionality and identity may cause conflict?

Nina: Oh, I am a strong believer in collaborative research. It is a very valuable way to conduct ethnomusicological research. Certainly, it helps to level the power asymmetries. It is not always easy, though. It requires a lot of willingness to leave behind some of those things which, in academia, belong in a longstanding tradition. Indeed, in academia, there are quite set ideas of how to go about ‘doing’ ethnographic research, but collaborators may have their own ideas! They have their own wishes and expectations of what they want from the research, and their own ideas of what they want to do. In many ways, we researchers come to the field with our ethnographic ‘tools’ that we use to approach certain contexts, but every setting is different. One should not think that it is easy. One must be willing to change course. Especially in terms of things, like, what are the research outcomes going to be? As researchers, we typically want to publish. Yet for our interlocutors, they may wish for the research to help them build an archive or to inform the public about what they do musically. The question in collaborative research then becomes a matter of how we go about combining these aspects.

And no, this approach cannot be used in every context. One’s interlocutors might not be interested in collaboration, or they might not have the time for it. In my case, they are often busy musicians! Everyone is living their own lives. Perhaps the answer would be that it should be implemented in contexts where that – collaborative research – is the initial idea, the premise.

Added question: Some ethnographers would challenge this question in asking, who do you ask to collaborate? In asking one person or a group, are you excluding others? There may be other interests or power relations within a certain space. So, how is that managed?

That can be very true in some cases. When I collaborated with members of The Quba Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies in Philadelphia, which is an independent Islamic day school, learning centre for adults and a mosque, the research team together decided that the community members would conduct the filming and most of the interviews. Because, of course, as for ethnographers and anthropologists, the question is, ‘whose voice’ is audible/visible? In shaping the fieldwork in this way, we were conscious of the camera as a very powerful tool, that the ethnographer utilises in choosing what to film – to be managed by the community.

Photo: Luis Quintero, pexels.com

Cris: [This argument] comes out of the context of increasing concern with research ethics and the change in the vocabulary of anthropologists. We used to talk of research subjects or informants, but now the discursive shift has renamed them ‘research participants.’ This sort of ethos originates from postcolonial critics and writers like Linda Tuhiwai Smith. Her book decolonising methodologies (1999) is on every research method reading list now. Linda argues that for Māori, ‘research’ is the dirtiest word in the English language. I know where this ethos comes from, but many people take that assumption and conclude that the ‘logical’ solution is for anthropologists to work in partnership with research collaborators so that research and writing become a co-authoring process.

I applaud the sentiment. You should always treat the people with whom you work with huge respect, and I think anthropologists do, mostly. But this argument is deeply flawed, and it assumes an outdated vision of what anthropology is or how ethnography works. Implicit in that assumption is this idea that the anthropologist is invariably the more powerful partner in that relationship. You [the anthropologist] are studying down and […] the process and the project would be more ethical and democratic if people were included as fully blown participants. It also relates to the discourse that says ethnography is invariably tainted because it is all about taking people’s stories and making your own career off the back of others.

What’s wrong with that assumption? Firstly, most anthropologists don’t work in that kind of environment. Most are working in contexts that you might define as, ‘at Home’. And if you’re studying the organisations which really do shape contemporary society, you are studying ‘Up’. The idea that you must make these organisations or their leaders (for example, politicians, managers, government officials, CEOs), research partners is unrealistic. You just wouldn’t be able to write anything, as you’d be giving these people veto over what you say or do. Even if you were studying, let’s say, a village in rural Italy or somewhere similar and you said, ‘Yep, I’m not going to be this objectivising person writing about their experience and their lives, I’m going to include them as full partners, full authors,’ that would still be problematic. The first thing anyone who does fieldwork in these kinds of community contexts would realise is that communities are riven with internal conflicts, competing interests and old animosities. So who are you going to include as your research participants in your collaborative, co-authored study? If you include one group and not the others, you’re just amplifying their viewpoint and excluding others.

Photo: Pixabay

From a different line of thought, Wasiq drew upon her 2021 collaborative project, entitled ‘Coming of age in indigenous communities: ageing, quality of life and home-based elderly care in Sápmi and Atayal region’. Upon reflection, Wasiq discusses the oftentimes difficult intersection between mainstream feminist theory and regional indigenous ontologies. In the larger SamiCare1 project, Wasiq and her co-writers were able to further nuance this discussion while remaining critical of their positionality as researchers and indigenous scholars.

Wasiq: In my experience, in talking with indigenous women and in indigenous studies, we have this strong idea that women’s indigenous voices should be heard. Women’s voices are legitimate voices. And this is because when we [academics] are talking about indigenous knowledge or indigenous wisdom, we are often talking about indigenous male wisdom rather than indigenous female wisdom or experience. For example, if we’re talking about hunting or traditional practices, these are often male-dominated experiences. As such, there’s not as much discussion of connecting with the land, which is more of a female experience. So, when I said to my research participants, ‘Oh, what you are doing is indigenous feminism!’, they were perplexed and didn’t quite know where I was coming from. Moreover, when we’re talking about feminism in the context of Taiwan, the discourse references this imported feminist ideology from the US, which is a very white and middle-class, urban-based version of feminism. An indigenous woman might have a vastly different way of achieving a certain goal, but because of social and historical experiences, this nuance gets lost if I call what she does feminism. In that sense, I’m also asking myself: how do I respect where they are coming from, and how do I say such things in a right and respectful way? It’s an on-going negotiation. We might not get it right on the first try, but we try again and make it an on-going process.

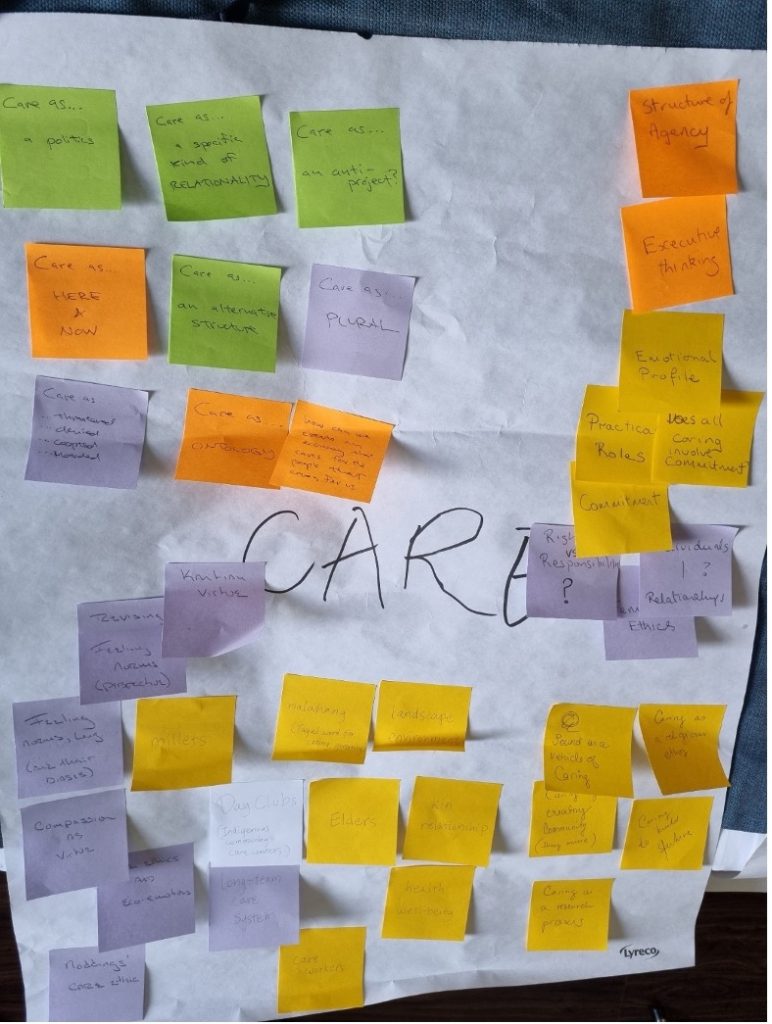

When considering collaboration, I’m reminded of the methodology that I used with my Norwegian/Sami collaborators in my previous project, where we used photo-voice as a way of trying to transform the ‘participant’ or ‘informant’ into partners. What we did was, we asked our partners to take a photo around a certain theme. This prompt might be, what makes you feel safe? or what is a Good Life for you? In asking this, we were mapping out what a Good Life means for them. But rather than ask and record an answer, we visited them more than twice and looked at their picture, together. So, it was not just text-based but visual. In doing so, they can use these images to help answer what it is that they are feeling. In essence, what we researchers did was try to amplify their voice rather than interpret it. I think this goes together with what Linda Tuhiwai Smith talks about. Even though we are doing decolonial research, the dynamic of who these people are is still unchanged. You, as the researcher, are still very much up in the pentagon of knowledge and you shouldn’t be! I think the researchers and people who are privileged with these tools need to be humble, no? To really help and elevate different forms of knowledge and different forms of epistemologies through, for example, using new tools such as photo-voice. We are still only at the beginning of thinking how we can put this into words.

The same question prompts different feelings both on the change in discourse and the ethics that are expected from the researcher when working with their research participants. The notion of power – who has it and what kind of authority it emits – is central. In Cris’s case, the idea of doing collaborative research may not only remove all power from the researcher but strip away any ability to be critical. However, for Nina and Wasiq, collaboration is essential. As Nina noted, the connection between researcher and participant can be fragile due to an existing history of trauma through the way in which their voices have been represented:

Nina: There are, in the world, sacred spaces and the knowledge that communities possess within such spaces should not be made public (unless said community wishes to make it public). We [researchers] should not expect to be able to access it, either. In my dissertation, I wrote about my research in African American church communities and how I, as a researcher, had to consider that I represented an academic research tradition which has a problematic past. A past in which white American and European scholars went into African American communities because they wanted to study some social ‘“problems’ or conduct unethical research, like the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Therefore, I was very aware of my positionality as a researcher and as a European white woman.

Photograph of Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Public Health Service. Tuskegee Syphilis Study. 4/11/1953-1972

The struggle of representation within African American communities during the late 19th and 20th centuries is a tragic period for anthropological and sociological research (Painter, 2010). Yet, as Wasiq points out, this trauma of representation continues to occur to this day. Thus, it is important to acknowledge that this article discusses the issues from a particularly ‘elite’ starting point. That is, how do highly qualified university researchers do research? Yet, the implications of reordering the relationship between researcher and researched has implications for authority figures within other institutions, as well. As Wasiq elaborates, the process of adapting alternative ontologies extends into ‘everyday’ interactions between indigenous or marginalised citizens and the State.

Decolonising Ethnography

Question: Mogstad and Tse (2018) argue, as do others, that there are places where anthropologists, ethnographers and researchers are simply not welcome due to a pervasive trauma of representation that has taken place over the centuries. How do you approach such a claim/have you encountered this in your own work?

Wasiq: It is a problematic intervention when the ethnographers come in and try to interpret your culture and capitalise on their observations without coming back. This kind of intervention makes me agree with these authors, and maybe such scholars can think of other places to go. It’s quite traumatic. I can think about what has happened in Taiwan, as there used to be a lot of researchers coming in, and they explained [that] the short life expectancy of indigenous people was due to indigenous peoples so-called ‘irresponsible behaviour’. These authors are not trying to solve the problem, but rather make people the problem. Unfortunately, this is now a perception of research from the collaborators point of view. From my perspective, you must see that indigenous societies and cultures are not living in a vacuum. We interact with the outside world. Therefore, it is necessary that we work together and welcome those researchers who want to wholeheartedly contribute to the decolonial goal. They can come in. But for those superficial people who are not genuine … we must come up with a cultural protocol where we must be explicit in addressing these researchers and demand from them, that if they come in, they must respect these things. This is something that indigenous researchers could emphasise when working with non-indigenous researchers in order to cement certain ground rules. But ultimately, it is important to work together so we can advance the interests of the communities and reach new directions.

For example, in social work. How do we decolonise social work? Social workers are very much needed and there are a lot of social workers in our communities; we cannot say no to them, as we are playing the same taxes and are therefore entitled to the same support as any other citizen. But, at the same time, we do not want them to come in and discriminate based on our indigeneity. Like, ‘let me tell you how to integrate into the wonderful life of being Han Chinese!’ No! I do not want this type of social worker. Instead, I want a social worker who understands where we are and works together and helps us achieve the goals which we want.

Again, both Nina and Wasiq present anecdotes in which the meaning of collaboration is truly empowering and reshapes the classic hierarchy of research and can radically alter the philosophy of, in Wasiq’s case, social work. Yet, one can see the situational nature of this type of discussion. In Cris’s case, the argument for the critical researcher’s voice remains integral.

Cris: I got criticised by a very well-known anthropologist who said, ‘I don’t know how you can talk about university managers like that. You are so dismissive of them. I’ve never heard of an account that was so derogatory towards your informants, your participants’. I was quite surprised to hear that, because I’m not talking about a community or group; I’m writing about a system that causes violence to the people below. And if I’m trying to do a critique of it, it’s not a personal attack on individuals but it’s a structural, systemic thing in the organisation of a workplace being reshaped by neoliberalism and capitalism. But, of course, there are some areas where I do a lot of self-censorship. There’s a lot I’ve discovered that I just think, ‘I won’t write about that’. It may be revelatory, but you don’t need to show where all the bodies are buried. It’s good to shine a light on systems and processes and structures, but I think you must be a bit cautious if in doing so you know that it will impact negatively on individuals. Ultimately, ‘do no harm’ should be a guiding motto.

Current debates on the ethics of doing ethnographic research are not easy. For the early-stage ethnographer, they can feel debilitating. Yet, the above interviews highlight the importance of context and how it is central to the way in which power is revealed and negotiated.

Whether studying ‘Up’ or ‘Down’, as the quote from Cris used in the title suggests, there are certain spaces that cannot be touched in the same immersive fashion of the classic ethnographers like Malinowski. When studying ‘elite’ spaces and institutions, the ethnographic concept of the field stretches into a different space. In other words, ethnographers interested in studying ‘Up’ are increasingly working undercover.

Yet, for those ethnographers who do opt to ‘pitch their tent’ in more conventional field sites, many may find themselves barred from such spaces. In such cases, rather than force their way in, ethnographers must adapt. Like Nina discusses, ethnographers must re-consider the aim of their research, to make it worthwhile to those who they wish to study. Moreover, the willingness to address the uneasiness felt within the legacy of many ethnographic 20th-century giants show the promise of ethnography to continue being critical. It is a matter of ‘Staying with the Trouble’ (Haraway, 2016). In that, through embracing our ‘response-ability’ (Haraway, 2016) as researchers by undertaking new forms of collaboration, we continue to recreate one another so to become something new. As a closing statement, this line of thought was further echoed by Wasiq:

Wasiq: We are both in the social sciences. Sometimes it is a very narrow space. There is a lot of normalising of what social science could be and should be. This is accepted by a certain standardisation, which is set by notions objectivity and other sets of Western ideals that explain what makes ‘good science’. I think the methods developed in indigenous studies could be very transformative. But there’s still a long way to go. Of course, a lot depends on the culture that is cultivated in specific research institutes and how much researchers could do transdisciplinary research, such as what we are doing here. With an open mind, there might be a new way of doing social science that [can be] combined with indigenous methodologies, especially when it comes to the world that we are living in, with climate challenges and sustainability issues. So, with different disciplines and those methodologies found in indigenous studies, I think it could be quite a push for a new way to think about the same old problems but in a different light.

Lois Watt is a master’s student in social and cultural anthropology at the University of Helsinki and a former research intern at the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies (autumn/winter, 2022). Her current research concerns the practice of open water swimming (otherwise known as ‘wild swimming’) in the Northeast of Scotland. The research project takes a specific interest in the intersections of gender, place-making and the more-than–human encounters experienced within sporting communities.

Bibliography

De Castro, E. V. (1998). “Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4(3). 469–488.

Delgado Rosa, F. & Vermeulen, H. (2022) “Before and After Malinowski: Alternative Views on the History of Anthropology [A Virtual Round Table at the Royal Anthropological Institute, London, 7 July 2022]” BEROSE Publisher

Haraway, D. J. (2016) Staying with the trouble: making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Malinowski, B. (1999) Argonauts of the Western Pacific: an account of native enterprise and adventure in the archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge.

Mogstad, H. & Tse, L. (2018) “Decolonizing Anthropology: Reflections from Cambridge.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 36(2). 53–72.

Munkejord, M.; Hætta, S.; Eira, J.; Glæver, A.; Henriksen, J.E.; Mehus, G.; Ness, T. & Silan, W. (2021) Coming of age in indigenous communities: ageing, quality of life and home-based elderly care in Sápmi and Atayal region Vadsø, Norge: Susannefoto Forlag.

Painter, N. I. (2010) The History of White people. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton.

Said, E. W. (1979) Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Smith, L. T. (1999) Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. London: Zed Books.