By HCAS Fellows Andy Graan, Charlie Kurth, Lilian O’Brien, Wasiq Silan and Nina Öhman

In the tranquil summer retreat of 2023, the fellows of the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies (HCAS) embarked on a journey to Haikko, a picturesque manor near the charming artisan old town of Porvoo. The purpose of the retreat was to foster interdisciplinary dialogue and conclude the productive academic year. While indulging in the seashore where one of the most renowned Finnish-Swedish painters, Albert Edelfelt, made his paintings, we delved into the intriguing topic of ‘care’ and explored its multifaceted dimensions. This blog post sheds light on our Mapping Care workshop, which brought together perspectives on care, ranging from indigenous studies and feminist theory to musicology, philosophy and more.

HCAS Fellows in front of the Haikko Manor in May 2023

The concept of care has been extensively analyzed and interpreted across various academic disciplines. From indigenous studies and feminist theory to political philosophy and queer theory, ideas about care have formed into an intricate composite of different meanings and applications. Recognizing the significance of care as a concept, our workshop aimed to create a safe space where we could share thoughts, exchange ideas, and collectively unravel the complex nature of care.

To kickstart the dialogue, two influential readings were circulated among us. The first was an essay by Sara Ahmed titled “Selfcare as Warfare,” which delved into the transformative power of self-care, drawing inspiration from the influential writer and activist Audre Lorde. Ahmed’s exploration of care as an act of resistance provided a thought-provoking foundation for the discussions that followed. The second reading, a chapter from Robin Wall Kimmerer‘s acclaimed book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, was titled “Learning the Grammar of Animacy.” In this chapter, Kimmerer elucidates the indigenous perspective on care by emphasizing the interconnectedness between humans and the natural world. By understanding the animate nature of all beings, Kimmerer advocates for a more respectful and reciprocal relationship with our environment. With the help of these two articles, we started a discussion about what ‘care’ may mean.

Weaving the meaning of care

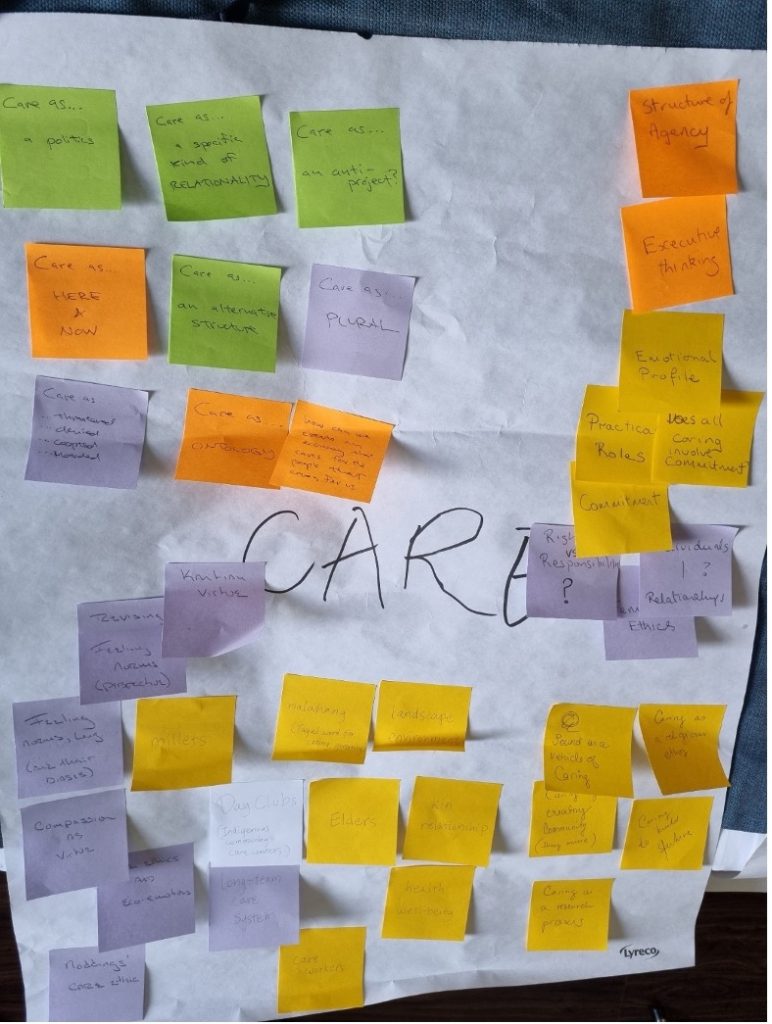

Our workshop became a collaborative journey of introspection and exchange. We started the discussion by mapping out what ‘care’ means to us in our current studies, and what we envision ‘care’ would be in five years. We wrote down what comes to mind, inscribing one or two keywords on post-it notes. Our goal was to create a visual storyboard showing how care takes form in our current and future projects. Here is a description of the storyboard of our creation.

Wasiq Silan:

I approach ‘care’ in relation to wellbeing and health in the Indigenous context. I started out to engage with notion of ‘care’ through my fieldwork at the day club, a social welfare project that takes place in many Indigenous communities in Taiwan to support older adults to age in place. Being trained in political science, my research design was to examine how Taiwan’s long-term care policies for the elderly impact older adults in the Indigenous communities.

However, I quickly realized being at the day club was like a ceremony that transformed my research, my positionality and the framing through which I see care. Namely, I am more interested in how Elders experience care, and more broadly what health and well-being mean in the Indigenous Tayal context. In practice, I followed my grandmother into the day club (community care center), using ethnography as well as Indigenous methodologies to make sense of what care means to the Bbnkis (Tayal Elders). I found out that contrary to the policies, where care is treated as a tool to delay the (often inevitable) functional decay, care for Bbnkis is relational. A way of life. Malahang (care, caring or governing in Tayal) entails strengthening relationships between people, humans and animals, and most importantly, with land.

In a similar vein, care workers in the Indigenous communities were under moral stress when they want to provide meaningful care to the Bbnkis. The stress points at a collective ethical labor that Indigenous care workers are subjected to when they decided to privilege Elders’ needs rather than policy guidelines. Care thus becomes a fundamental site of struggle in the wider Taiwanese policy environment where decolonization was only beginning.

What does it look like in 5 years? I envision further developing the framework of care in the context of Tayal knowledge. Specifically, I aim to collaborate with community researchers through Indigenous methodologies to explore caring about relations within millets growing.

Andy Graan:

My current research focuses on projects and the model of agency that is presupposed by the project form. Projects are based on the historically specific assumption that society and nature are objects that can be transformed and they position human actors as the agents who both envision and execute transformation. This model of agency underwrote the myriad modernist projects that resulted in rapacious European colonialism, the enclosure of the commons, and constitutional government, just to name a few. Moreover, this model of agency perpetuates technofuturism as a hegemonic form of problem solving in the world today.

My interest in “care,” then, stems from my desire to denaturalize and provincialize the project form as a model of action. Projects are premised on human subjects acting on natural and social objects. Care, however, as articulated by thinkers working in the fields of feminist philosophy, Black feminist theory, and cultural anthropology, describes a different kind of social relation and a different model of action, one based on reciprocity, mutuality, kinning, respect, and solidarity. Care is focused on the here and now, rather than on speculative futures. Care can be a praxis of refusal and survival, of denying dehumanization and oppression, of continuing to live after apocalypses.

Indeed, groups facing marginalization and abjection—women in patriarchal societies, the enslaved, the indigenous, the poor, those subjected to apartheid and occupation, refugees, and immigrants—have born the greatest burdens of care but have been its most profound elaborators and practitioners. Everyday care practices too often go unrecognized while commodified care practices are hoarded by some and denied to others. As I see it, then, the literature on care provides us with an important provocation. In elevating practices of reciprocity, refusal and survival, it punctures recalcitrant myths of progress (for whom?) and centers the fiercely mundane labor of living together.

Lilian O’Brien:

In my current research I am very interested in the nature of commitment – committing to plans and principles is central to our ability to function as social agents who coordinate and co-operate with others. Committing is also something that can give meaning and value to our lives, when, for example, we commit to caring for and supporting others in close relationships.

I am interested in the relationship between committing and caring. They seem to be interdependent, at least sometimes, and I would like to better understand this relationship of interdependence, how they are different from, or similar to, one another, how they may reinforce one another, but also how they may be in tension with one another. Is committing to promoting the well-being of another necessary for caring for them? How does and should caring for another be constrained or informed by prior commitments to plans or principles that are unconnected to caring for the other? The discussion at our care workshop has helped me to appreciate the complexity of the concept of care.

The other area in which I have thought about caring is in the context of feminist philosophy, and specifically, in feminist ethics. Feminist philosophers have argued that ethical theorizing, which has in the past been dominated by male philosophers, has neglected relationships of caring that are found in everyday settings, particularly in domestic settings where, for example, parents care for children, where children are taught to care for one another and for nonhuman animals, their environments, and so on.

Some feminists have thought that ethics should have care at its core – ethics should be much less focused on the rights of freely contracting individuals and should instead focus on the relationships of responsibility that we have to one another in social settings. Whether or not that revisionary view of ethics offers a clear and plausible alternative remains to be seen. But even if this radical revision does not work, it would be an impoverished ethics that did not take seriously the ethical issues that arise because we are the kinds of creatures who are embedded in caring relationships.

Nina Öhman:

I have not yet used “care” as a concept in my current research, but I have become inspired by its potential to elucidate – or should I say amplify – the audible bonds people build with each other. As a musicologist, my research engages with sound and recently I have been thinking about the many ways in which the idea of care guides musical lives of individuals and communities. And how I might understand and write about caring in its myriad sonorities. On the one hand, a well-known approach is music therapy as health care, but on the other hand, caring / uncaring can be seen more broadly as the power of music to soothe, or trouble, our lived experiences. Furthermore, music in communal life can express values and enforce relationships, conveying caring for one another. Yet, music can also be used destructively, for example to disturb peace, for harmful or purposeful noise, demonstrating carelessness or uncaring.

Additionally, I have thought about what the idea of care might mean for us as researchers in our work. Instead of assuming the position of a so-called objective observer, I ponder how might we engage in our work as thinking and feeling individuals enacting care. I still have a lot to learn and understand about this topic, but surely care is an integral part of the dialogue we have with our interlocutors.

Charlie Kurth:

In my research and teaching, I’ve approached care from a variety of perspectives: within biomedical ethics, as a way to understand the complexity of the doctor-patient relationship; within normative ethics, as a feminist-inspired alternative to ethical theory; and in my work on moral psychology, as a label for a range of related, morally significant emotions—compassion, empathy, concern, and the like. The workshop gave me the opportunity to think not just about these facets of my work, but also gain further insights from the other participants. On this front, the discussion helped me see that talk about ‘care’ is much more conceptually rich and complex than I had appreciated.

Conclusion

With our reflections on what role ‘care’ plays in research, we can begin to recognize how our work is deeply entangled with care and (un)caring across different disciplines. Care encompasses the future, but even more so it is about here and now; care is an embodied experience, but it also transcends; care seems to evoke personal emotions, but it also triggers relational commitments that at times are even inseparable from the communities one cares about. Care is both mundane and sacred. Care has aspired to be turned into practice that empowers and transforms. Meanwhile, care continues to be practiced every day, largely unnoticed, likely devalued and may hardly be reciprocated.

To summarize, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s language game (see endnote below) may be helpful: there will be no one thing common to all forms of care, and no successful characterization of it in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions, but that there will only be “family resemblances” among a variety of things that deserve the title “care”.

The HCAS retreat of 2023 served as a platform for us to collectively explore the multifaceted nature of care. The workshop—and the retreat as a whole—fostered a safe space for intellectual growth, encouraging us to challenge preconceived notions and develop a deeper understanding of amorphous concepts, such as care. By bringing together various disciplines, the Collegium’s retreat demonstrated the power of interdisciplinary dialogue in enriching the depth of our thinking.

Endnote: Ludwig Wittgenstein: Philosophical Investigations, sections 65-67:

- You talk about all sorts of language- games, but have nowhere said what the essence of a language-game, and hence of language, is: what is common to all these activities, and what makes them into language or parts of language. So you let yourself off the very part of the investigation that once gave you yourself most headache, the part about the general form of propositions and of language.”And this is true.—Instead of producing something common to all that we call language, I am saying that these phenomena have no one thing in common which makes us use the same word for all,— but that they are related to one another in many different ways. And it is because of this relationship, or these relationships, that we call them all “language”. I will try to explain this.

- Consider for example the proceedings that we call “games”. I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games, and so on. What is common to them all?—Don’t say: “There must be something common, or they would not be called ‘games’ “—but look and see whether there is anything common to all.—For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don’t think, but look!—Look for example at board-games, with their multifarious relationships. Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to ball- games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost.—Are they all ‘amusing’? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball games there is winning and losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Look at the parts played by skill and luck; and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think now of games like ring-a-ring-a-roses; here is the element of amusement, but how many other characteristic features have disappeared! And we can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way; can see how similarities crop up and disappear. And the result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail.

- I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than “family resemblances”; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, etc. etc. overlap and criss-cross in the same way.— And I shall say: ‘games’ form a family.