By Keith Brown

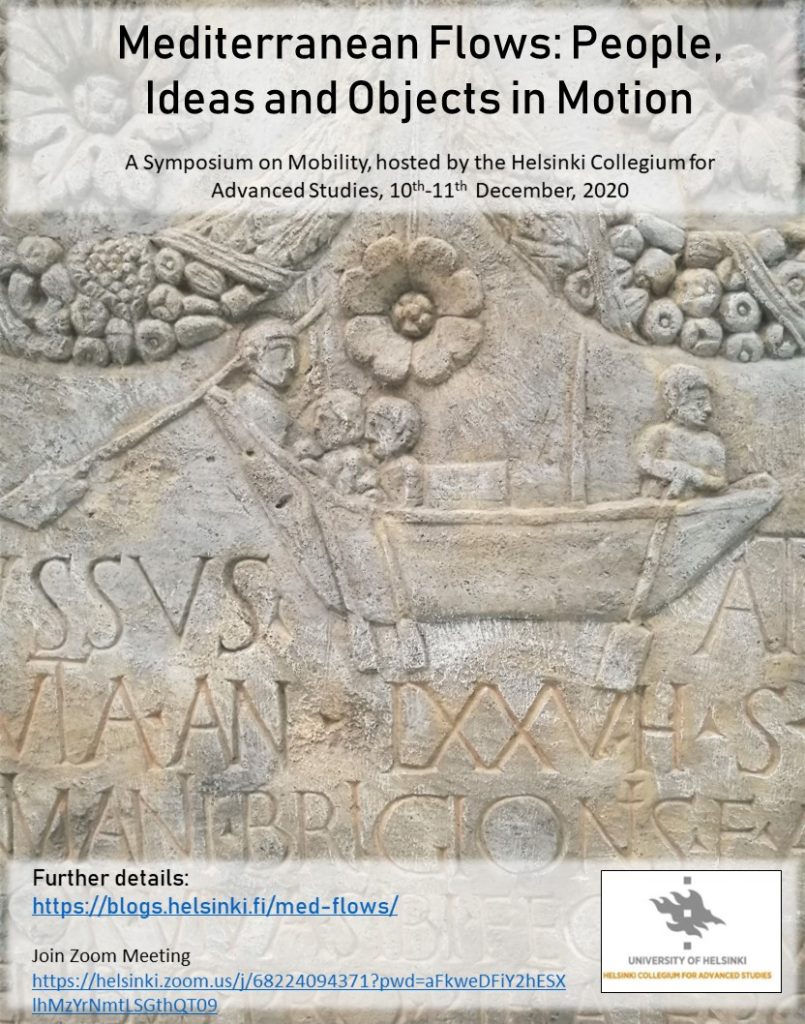

The recent debate at the University of Helsinki around the beloved Finnish boardgame Star of Africa—and in particular how to respond when cherished family traditions turn out to be vehicles for the unwitting transmission of racist stereotypes—hit home for me. I have my own warm memories from growing up in England, playing games like the 1938 Buccaneer or the 1965 Mine-a-Million where the goal was to bring riches home from exotic locations.

We didn’t ever talk about race and racism. It wasn’t, after all, a life and death issue for my parents or for me—the way it is, so immediately, for black families in the United States. I knew nothing about sundown towns or “the talk” that most black parents have with their children, in the hope it will save their lives when—not if—they are stopped by police officers.

Instead, I enjoyed the privilege of obliviousness. As we played those games, or when the stick-figure battle scenes I drew included British soldiers fighting off Zulu attackers, neither my teachers nor my parents took it as an opportunity or an imperative to discuss the ways in which the modern world, and our own privileged position in it, was the product of resource-transfers and ideologies of white entitlement that were shaped by conquest and colonialism. Like most of the enthusiastic British audience of the still-popular feature film Zulu, which tells the story of the heroic defense of Rorke’s Drift, I never asked, or was asked, what exactly the British army was doing in the middle of Africa.

50 years on, even after studying for a doctorate in anthropology and teaching international relations and global studies for almost two decades, I still have a lot to learn. That’s been especially clear to me over the past decade, as a naturalized U.S. citizen witnessing the heightened political polarization that followed the election of the country’s first black President. And even more so, watching the attack on the US Capitol on January 6 2021 and the disinformation that preceded and followed it.

I say witnessing and watching, because even though my wife and daughter are American-born, I have maintained the illusion that my English roots make me an observer, rather than participant, in America’s long struggle with its racist roots. Graduate school room-mates in Chicago had to instruct me on the significance of Harold Washington’s legacy as the city’s first black mayor. And it was later still that I came to appreciate the distinctive legacy of Martin Luther King; both his commitment to non-violence, and his dream that future Americans would be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I still struggle to understand how anyone of good conscience can support action or speech that opposes those values. I know that some people, wittingly or not, do; but I’ve imagined that they and I have little or nothing in common.

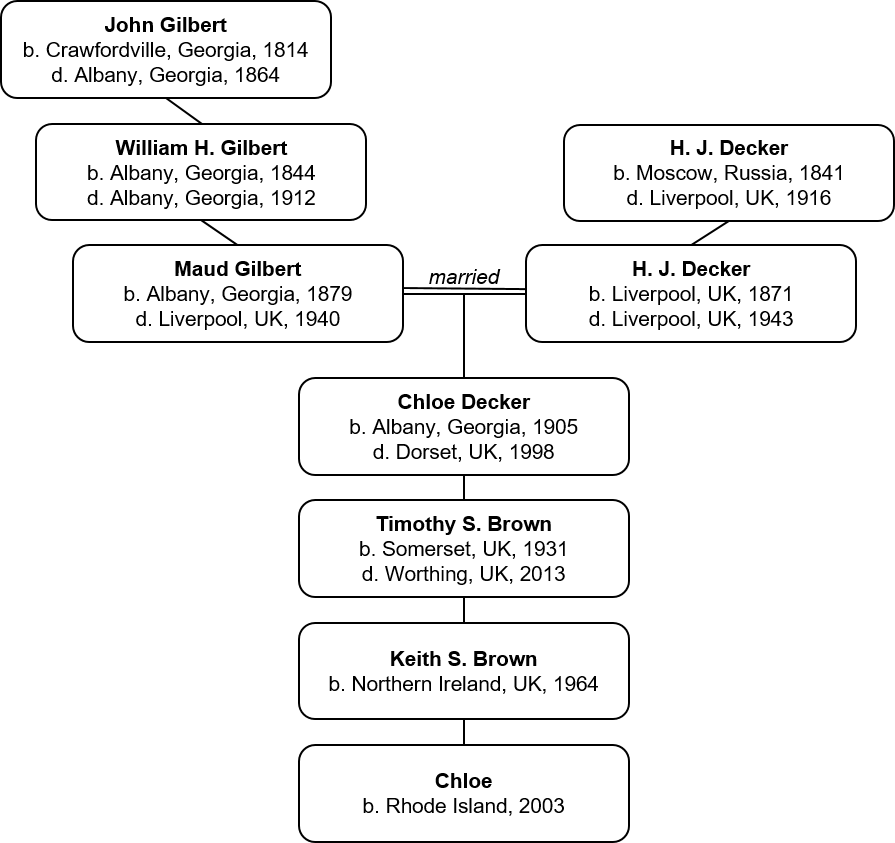

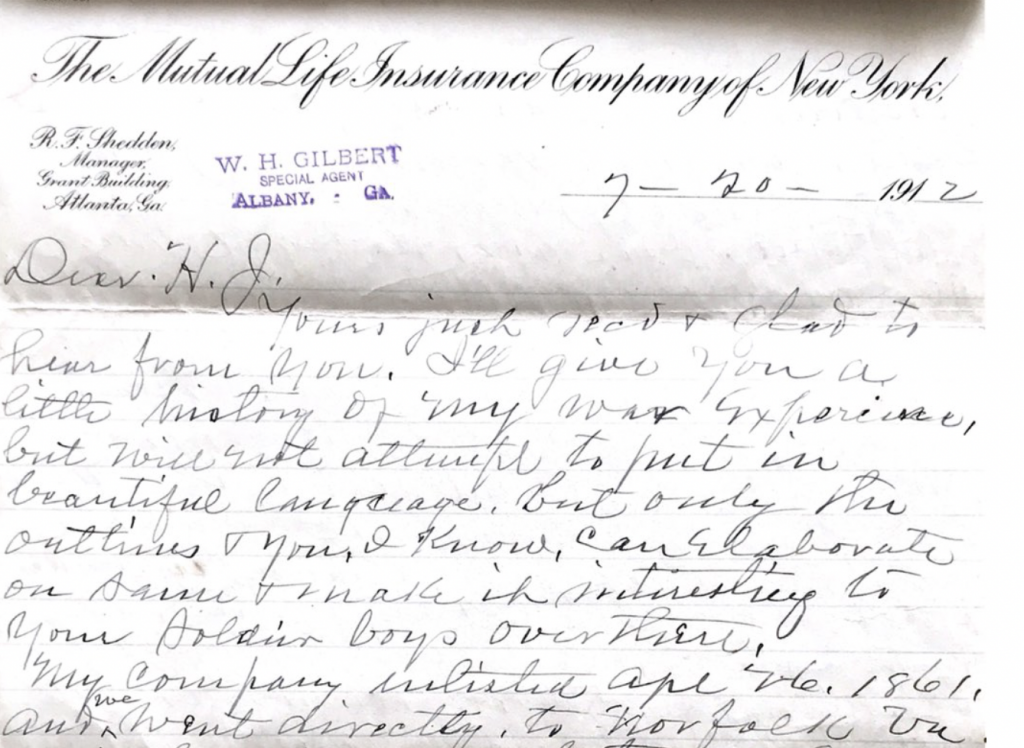

And then, last month a letter I found in my parents’ flat shattered my illusions of innocence. Sorting through my late father’s papers, I found an envelope, postmarked Albany, Georgia, USA, and addressed to my great-grandfather, H.J. Decker, in Liverpool, England. Inside was a ten-page handwritten letter from his father-in-law, W.H. Gilbert, bearing the date July 20 1912. And on the very first skim through, on the penultimate page, two sentences stood out, which included the names of H.J. Decker’s wife and W.H.Gilbert’s daughter (Maud), and H.J.’s daughter and my beloved grandmother, after whom we named my own daughter (Chloe). Those sentences first bound me intimately to the sender and recipient, by naming the person we knew in common; and then repelled me. “Give lots of love and kisses to Maud and the kids,” writes W.H. Gilbert. And then, breezily, with no inkling of how his choice of words might resound decades later, “What did Chloe think of the postcard I sent her? ‘N***** in a cotton patch.’”

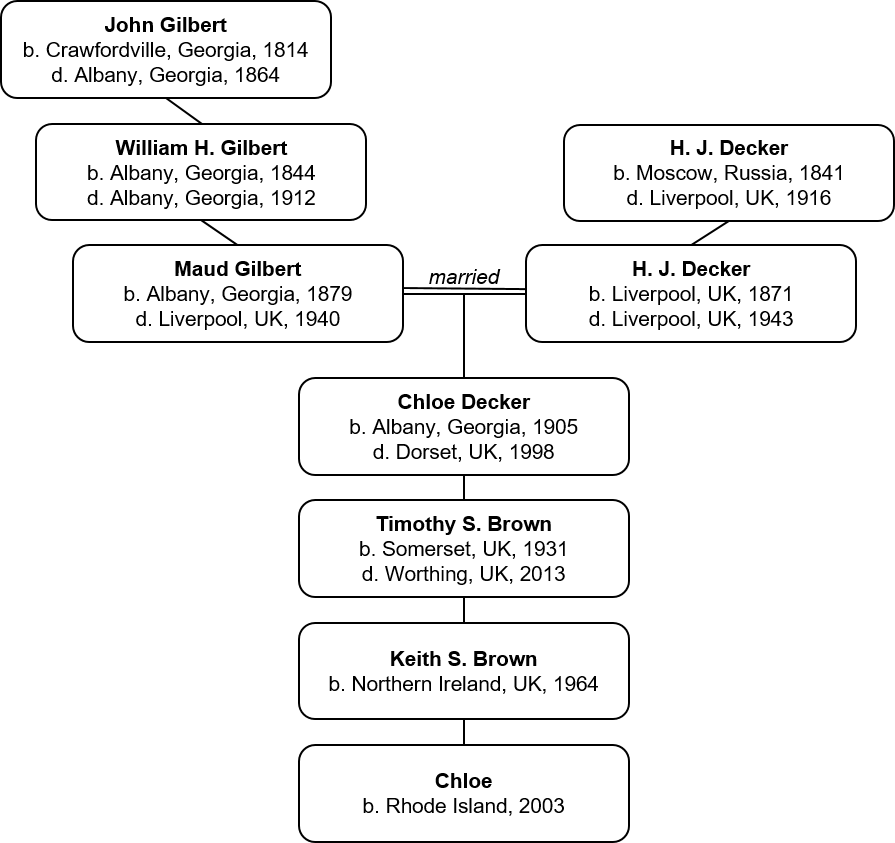

I had known that my grandmother Chloe was born in Georgia and spent significant time there in her youth. I recall also that, early in my teaching career in anthropology, she and I had at least one conversation about race, in which I tried to articulate to her the value of cline theory in helping students understand that racial boundaries are not inscribed in biological difference, but are rather culturally and socially constructed. We didn’t agree. And perhaps for that reason, our conversations tended to focus on the more exotic and glamorous side of her family heritage; her Russian émigré grandparents, H.J. Decker’s parents, who left Moscow soon after their 1861 wedding to settle in Liverpool.

Gilbert-Decker-Brown Family tree. Graphic: Anita Mezza.

As Canadian-Scottish journalist Alex Renton discussed in the context of his recent book Blood Legacy, doing family history is not about passing judgement on our ancestors’ characters. It represents the opportunity and the debt we owe our elders to pay attention to the clues they leave behind, as we struggle to try to leave the world better than we found it for our children. I treat this letter, then, as a gift handed down through 3 generations, and seek to honor the legacy by trying to understand what they are telling me. I take as the core challenge—still relevant in these polarized times—to explain how good people embrace and pass on bad ideas.

The Experience of Combat

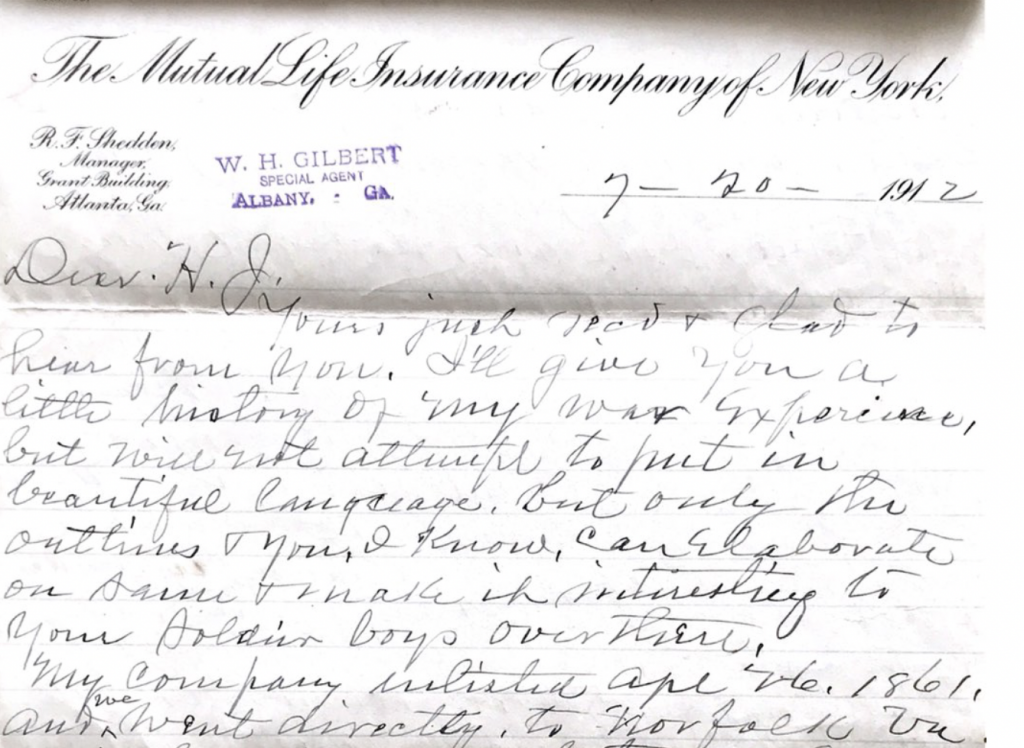

The start of Gilbert’s letter emphasizes an aspect of life that evokes our enduring curiosity and interest. Gilbert expresses as his goal to provide “a little history of my war experiences” on which, he hopes, his son-in-law H.J. can “elaborate… and make it interesting to your soldier boys over there.”

The opening of the letter.

In 1912, H.J. was a commissioned officer in Britain’s Territorial Force, established in 1908 as an Army reserve. His day job was as a cotton broker—the profession he had entered direct from Sedbergh School in 1890, and which had brought him across the Atlantic to the American South almost every summer. In the course of multiple visits to Albany, he and Gilbert had surely had prior conversations about combat, and H.J. had now solicited a written narrative that he could share with the young soldiers in the artillery unit that he would go on to command during the First World War (1914-18).

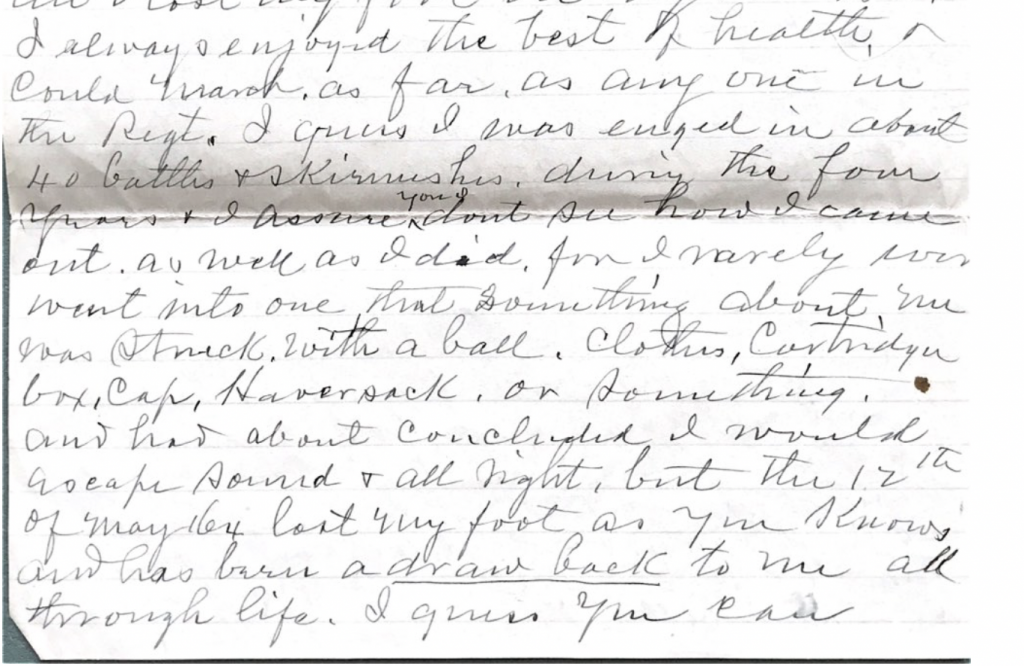

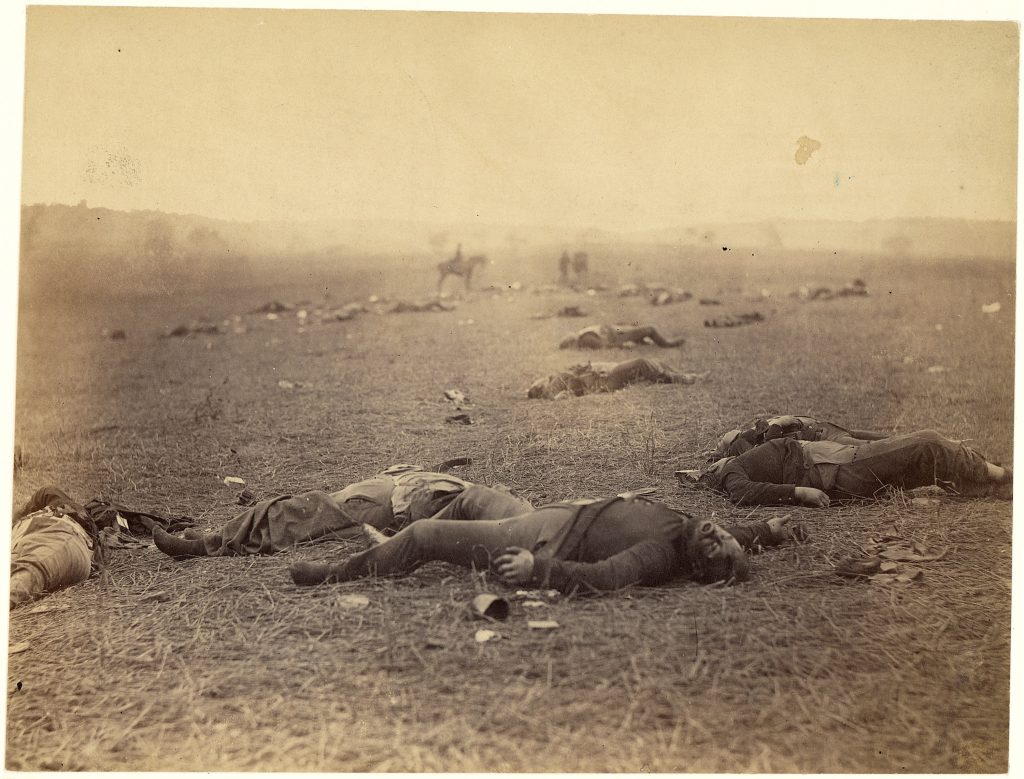

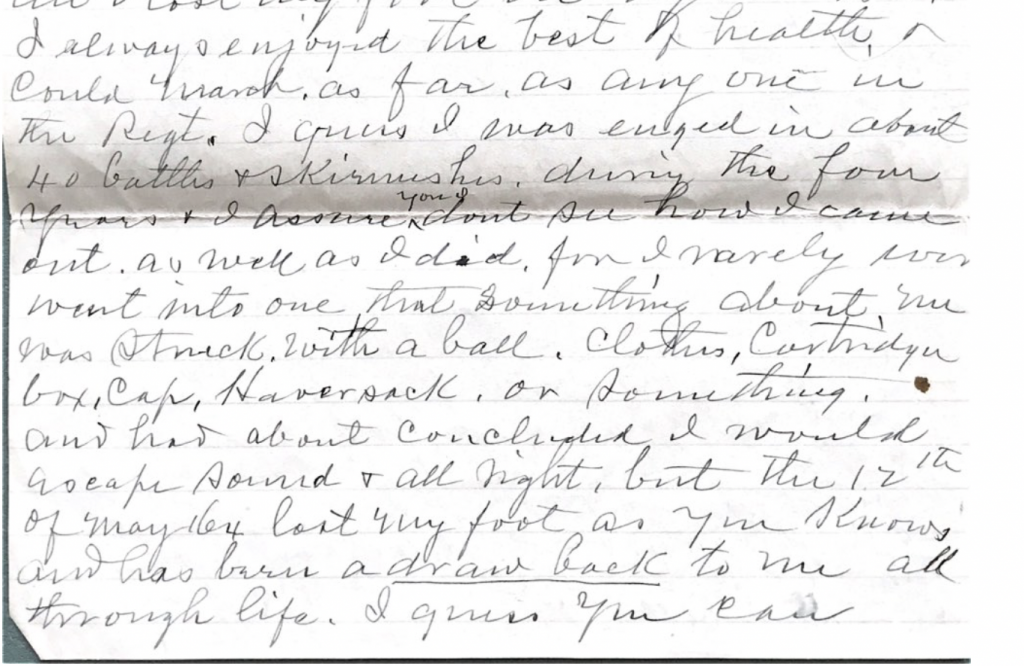

Gilbert’s narrative ties me back to the US Civil War (1861-65)—and specifically, to the Confederacy of eleven Southern states which broke from the North after the election of President Abraham Lincoln. W.H. Gilbert enlisted as a volunteer in Georgia in April 1861, at the rank of private. The letter provides a chronology of his active service, listing sixteen “big battles” in which he participated, including 2nd Manassas (Bull Run, August 1862), Sharpsburg (Antietam, September 1862) and Gettysburg (July 1863). Reflecting on his extended service, Gilbert marvels at the charmed life he enjoyed for so long, and reports the moment his luck ran out. “I guess I was engaged in about 40 battles and skirmishes during the four years, and I assume you don’t see how I came out as well as I did, for I rarely ever went into one that something about me was struck with a ball. Clothes, cartridge box, cap, haversack or something, and I had about concluded I would escape sound and all right, but the 12th of May 1864 I lost my foot as you know, and has been a drawback to me all through life.”

Luck and loss.

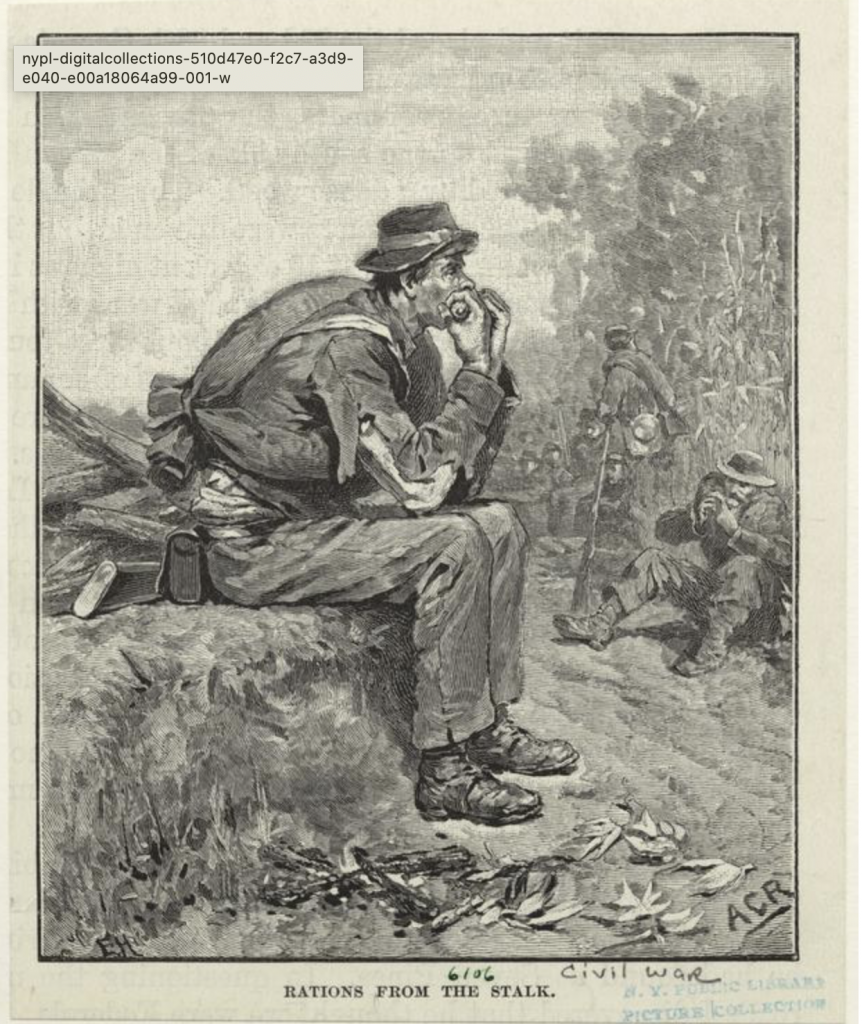

The letter includes other details of the experience of war. He recalls the hardship of life on short rations, especially in the campaign leading up to Antietam, which other veterans also described as the ‘Green Corn Campaign.’” He recalls the carnage of the battlefield at the 2nd Manassas, where “…we met a Brigade of Red Pants, …, Zouaves, and when the battle was over, one could walk full length of the Brigade on red britches, I never saw such a destruction of life in my life, red britches were discarded after then for they made too good a target.” He speaks proudly of his own and his fellow-soldiers’ resilience and undertaking long forced marches where he saw “many a soldier marching without a shoe on and almost without clothing.”

Image: A.C. Redwood, Courtesy, New York Public Library, Digital Collections.

He mentions crossing the Potomac after Gettysburg, when ”water came up to my armpits and we tall men had to float the little fellows over.” And the experience of sleeping in the open, utterly exhausted, and waking up to find the camp was blanketed with snow. These vivid, telling details are the common stuff of military memoirs, recalling comradeship, horror and a sense for the suffering and loss on both sides.

Trauma, Heroism and Impossible Odds

Understandably, Gilbert’s writing dwells in particular on his own personal trauma. He was at the “Horseshoe”—a defensive position designed to exact heavy losses on Northern attackers during the Battle of the Spotsylvania Courthouse—when he lost his foot. After first mentioning his injury, Gilbert then refers to the wound and its long-term negative effects four times in the course of ten sentences. He also reports his brother’s death at the fall of Petersburg (March 1865).

Apart from these intimate losses, and the description of piled bodies at the 2nd Manassas, the only other death he describes in the letter is Stonewall Jackson’s, in May 1863. Gilbert had already praised Jackson’s leadership, drive and inventiveness, and devotes extended time to the moment that he, like others, saw as a tragic turning point for the war effort.

The day he was killed, or wounded and died from his wounds, at Chancellorsville, he marched us 23 miles by 2 o’clock on a flank movement and we drove the enemy 3 miles by nightfall, with a terrible loss to them in killed and wounded, and we captured around 4000 prisoners and 16 pieces of artillery and that night he lost his life, which in my opinion broke the back of the Confederacy, because we never could fill his place.

Gilbert’s focus and tone, up to this point in the letter, highlight how the Confederate army’s prowess, combined with its leaders’ skill and cunning, brought early battlefield success. From this moment on though, the letter’s tone shifts, emphasizing that Confederate bravery and skill is not enough to overcome their foes’ superiority in numbers. On the first day of Gettysburg, he writes, “Our brigade drove the enemy through the wheatfield and city and our casualties were very small, but we gave them a terrible loss, but of course we could not hold it, for the odds were too great.”

And when reflecting on the larger course of the war, later in the letter, he inserts an observation about the ultimate reason for the war’s outcome. “I shall always believe that had Jackson lived, we could have gone into Washington from Gettysburg” he writes. But then he adds, “I don’t think we could have held it, for the reason we fought the entire world, capturing a good many who could not speak a word of English.”

This comment is consistent with data on the significant role of first-generation immigrants in the Union Army. Most historians of the Civil War also agree that Jackson’s battlefield leadership was charismatic and dynamic; that Robert E. Lee was a highly effective general; that Gettysburg marked the decisive turning point of the war. Once the Confederate attempt to enlist foreign assistance against the Union failed, the industrial and numerical superiority of the North was bound to prevail in the war of attrition.

“Lost cause” and preserved convictions

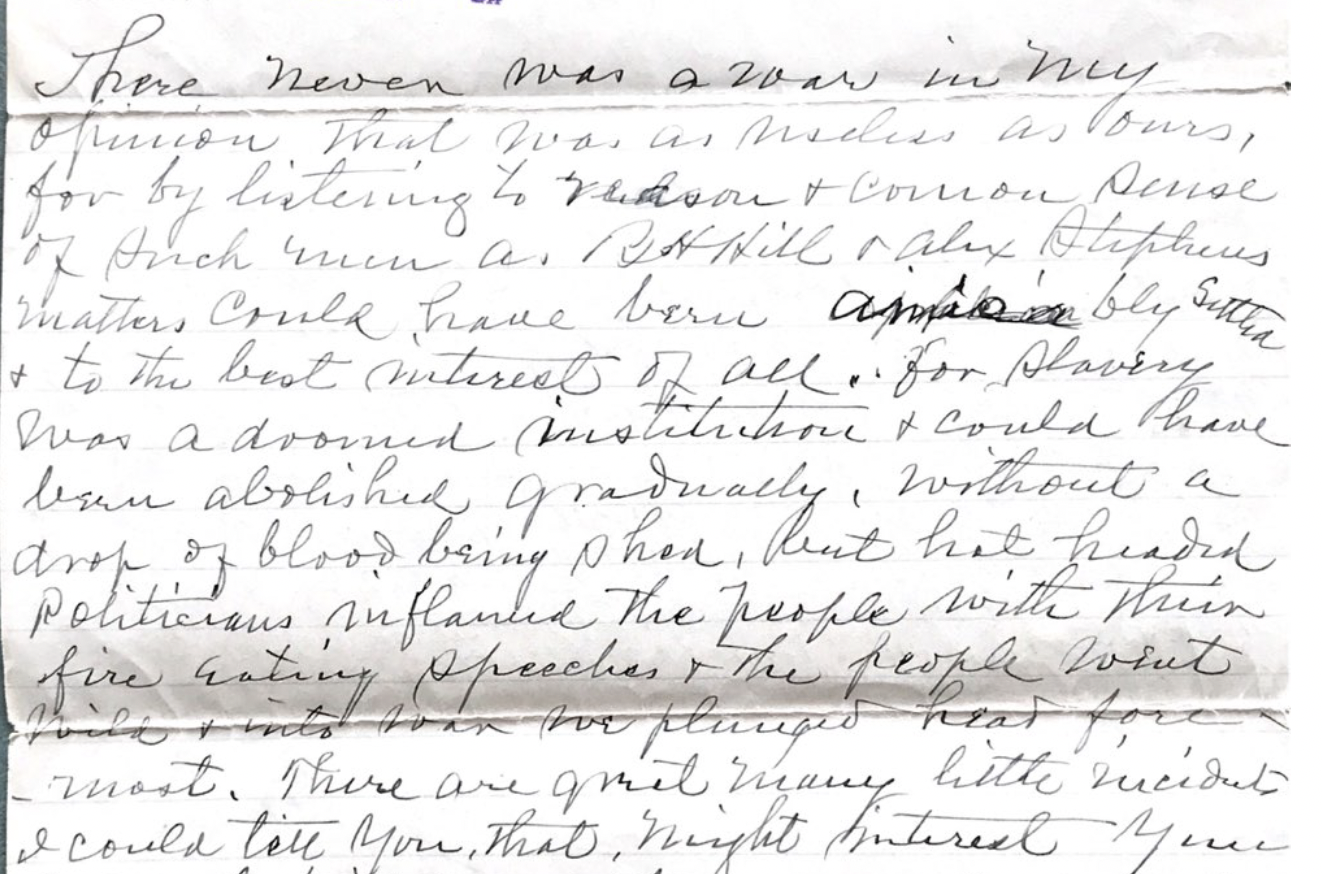

Gilbert then builds on these data points—derived from his own intimate and immediate experiences of combat—with a reflection that is more open to question. He first makes what looks like a straightforward statement in favor of peaceful negotiation over deadly war, writing “I had enough fighting then to last me up to date and a poor settlement is better than one fight.” He then shares with H.J. his larger perspective on the causes of the war in which he lost so much, writing:

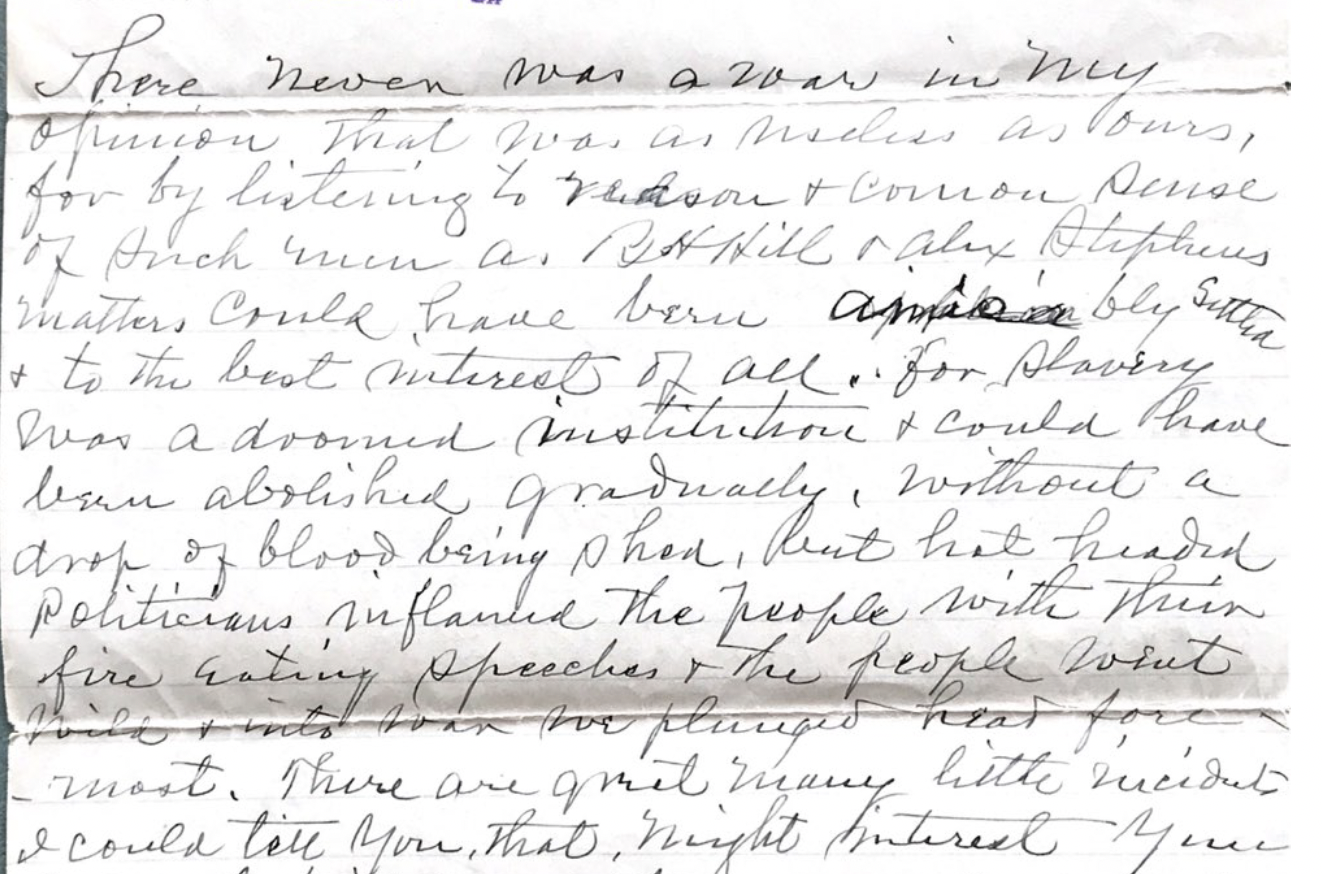

“There never was a war as useless…”

There never was a war in my opinion that was as useless as ours, for by listening to reason and common sense, of such men as B.H. Hill and Alex Stephens matters could have been amiably (sic) settled. And to the best interest of all. For slavery was a doomed institution and could have been abolished gradually, without a drop of blood being shed, but hot-headed politicians inflamed the people with their fire-eating speeches and the people went wild, and into war we plunged head fore-most.

The two men referred to here as champions of “reason” and “common sense” were both professional Georgian politicians. In the run-up to war in the 1850s, both had opposed secession on grounds of Southern self-interest. Both held office during the Confederacy—Benjamin Hill as senator, and Alex Stephens as vice-president. Both were jailed after the war before returning to public life and elected office. They were both fierce critics of the ideas and practices of Reconstruction—the period of 1865-1877 in which serious and sustained efforts were made to undo systems of racial inequality across the South.

In Dreams of a More Perfect Union, Rogan Kersh offers a close reading of Benjamin Harvey Hall’s strongly worded critique of the impacts of Reconstruction in Georgia, delivered in speech at Atlanta’s Davis Hall in 1867 and reiterated in the widely circulated “Notes on the Situation.” He disputed the war’s victors’ claim to represent the Union, insisting instead that “This is not the Union of our fathers. This is, emphatically, a Reconstructed Union.” Hill told his Southern audience that both during the conflict and in its immediate aftermath, they had been targets of “a diabolical sectionalism in the very teeth of every principle of the American Union” (cited in Kersh 2001: 198). In Kersh’s analysis, Hill advanced a vision of the Union with “space for southerners to manage local affairs, and particularly to determine the status of blacks in the region” (2001: 222).

In 1861, Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens laid out what was at stake for the South in his “Cornerstone” speech. Speaking to an enthusiastic crowd, he made the tendentious claim that the Founding Fathers’ criticisms of slavery as a violation of natural law were mistaken. Their error, in Stephens’ argument, was the cause of the political crisis of the Republic, and the government’s fall. In the same logical vein, he labels abolitionists as fanatics who demonstrate a “species of insanity” because, “they were attempting to make things equal which the Creator had made unequal.” Invoking divine authority, Stephens asserts that the new Confederate constitution would correct this fatal flaw.

Writing after Stephens’ death in 1883, A Macon Telegraph writer recalled that Stephens “always prided himself on what he called his “corner-stone” speech, wherein he declared slavery the great corner-stone of the new republic.” Kersh describes Stephens’s post-war views as demonstrating “warmed-over confederate doctrines” (Kersh 2001: 221). An example of Stephens’ revised language but unchanged mindset appears in his 1868 A Constitutional View of the Late War between the States, in which he claimed that the labor system in place in the antebellum South was “so-called” slavery, which in his words “was not Slavery in the full and proper sense of that word” but was rather “a legal subordination of the African to the Caucasian race” (1868: 539).

In his choice of figures to praise, and in the statement that slavery was an insufficient reason for the war, Gilbert tacitly endorses what numerous historians—including Gaines Foster, Gary W. Gallagher, Alan T. Nolan, David Blight and Nicole Maurantonio—identify as Lost Cause mythology. By denying that slavery was the sectional issue, Lost Cause ideology painted the South as the true heirs of the Constitution and the North as the aggressors. Lost Cause ideology continues to distort U.S. understandings of the past, and underpins contemporary racism. When Gilbert refers to “hot-headed politicians” with their “fire-eating speeches”, it is possible that he is thinking primarily of abolitionists like John Brown and William Lloyd Garrison, whose actions and speeches in the 1850s were widely seen by Southerners as both treasonous and anti-Southern, thus affirming the perspective that the Confederacy preserved what was “best” in the Constitution. It may also be a more general attack at Republic politicians—starting from Lincoln himself, and including those advocates of post-war Reconstruction—whom Gilbert viewed as posing a threat to his America.

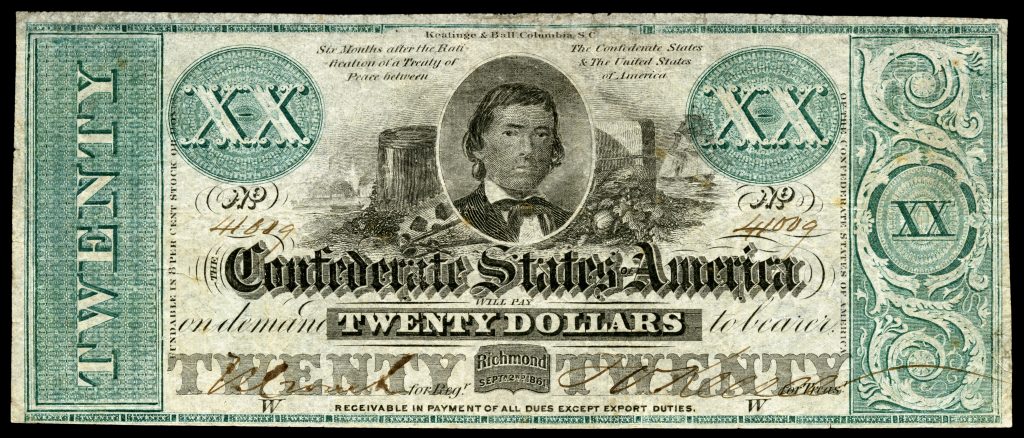

Lost inheritance, and Recovered Status

W.H. Gilbert’s combat experience, clearly, was formative in shaping his worldview. So too, it appears, was his family background. In post-war census records, he is identified as a druggist, so a medical professional. His father, John B. Gilbert, is identified in the 1850 and 1860 censuses as a physician. In the year before his son W.H. Gilbert enlisted, John Gilbert’s real estate was valued at $19,500, and his personal estate at $42,950 (or around $650,000 and $1.4 million respectively, for a total worth of just over $2 million, in 2021 equivalents).

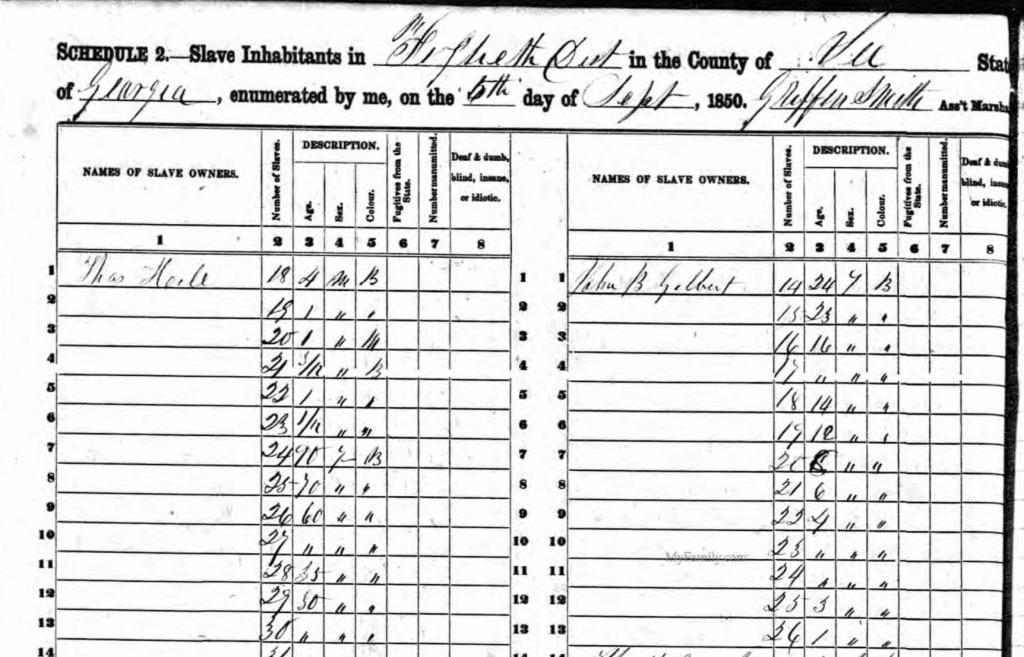

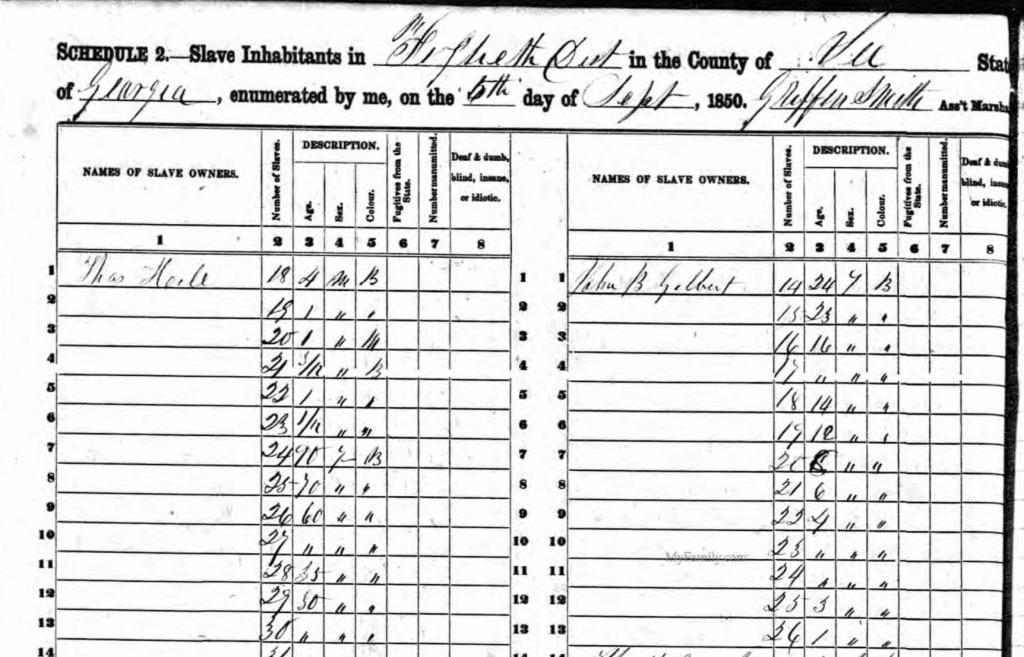

The high value of his personal estate was a function not of John Gilbert’s medical practice, but a second profession also listed in the census: farmer. Like many white families in the territory referred to as the “Black Belt,” the Gilberts derived income from cotton farming. In this regard, John B. Gilbert’s prosperity was a product of rapid transformation between the 1780s and 1830s, as state leadership encouraged settlers to invest in lands expropriated from the Cherokee and Muskogee nations. John Gilbert was born in Crawfordville, Georgia in 1814, just three years after Alex Stephens, who returned to the town to live out his old age at Liberty Hall. John Gilbert achieved financial security by moving north into territory made available by the 1830 Indian Removal Act. His personal estate valuation includes enslaved men and women: the slave registers for Lee County in both 1850 and 1860 identify John B. Gilbert as the titular owner of 26 (unnamed) people—almost certainly the labor force on a medium-sized cotton plantation.

Excerpt from the 1850 slave register of the US Federal Census, Lee County, Georgia, with entries #14-26 of unnamed enslaved people, in John B. Gilbert’s legal ownership.

John B. Gilbert died in January 1864, while his sons W.H. Gilbert and Rudolph were still on active service. He therefore did not live to see the break-up of the plantation which had depended on the labor of enslaved people. Most likely, the Gilberts’ land in Lee County followed the evolution of the estates around Albany that W.E.B.Dubois describes so vividly from a visit in at the turn of the century in the Souls of Black Folk, when he found scenes of “…phantom gates and falling homes… all dilapidated and half ruined” (Du Bois 1903/2007, 86). Mindful of historical change and conscious of the wars waged against the indigenous owners, the violence of the plantation system, and also of the asset-stripping that followed the Civil War, Dubois invokes an image of biblical retribution. “This was indeed the Egypt of the Confederacy,” he writes, as if mindful of Gilbert’s own recollections of campaigning, “the rich granary whence potatoes and corn and cotton poured out to the famished and ragged Confederate troops as they battled for a cause lost long before 1861” (ibid., 86).

W.H. Gilbert, though, parlayed this lost inheritance into a new venture, entering politics with some success. He took a prominent role in veterans’ organizations, serving as president of survivors of the 4th Georgia Regiment. The Macon Telegraph reported from an 1893 reunion that Gilbert, now holding the rank of Captain, “carries more than one scar to attest his courage upon the field.” He drew on his war record, and his father’s former standing, to win election as a city alderman as early as 1870, aged 26, before serving five year-long terms as Mayor of Albany, in 1885 and then from 1891-1895.

This family letter, then, is not just the reflection of an old war veteran, sharing experience down the generations with the young soldiers whom his son-in-law will lead to war in France within two years. It also offers a glimpse of a world, which venerated Confederate bravery and gallantry in defense of true American values against all enemies. It reveals that early this century white Southern voters continued to elect officials who believed in the justice of the cause for which they had sacrificed and who read and endorsed authors who maintained and propagated white supremacist ideologies.

Historical voices, contemporary echoes

And finally, Gilbert’s letter shows how ideas about racial stereotypes get passed on without anyone really paying attention. We don’t know for sure exactly what Chloe’s postcard from her doting grandfather looked like. Most likely, it followed the genre used in advertising and other representations of the time, showing black people alongside cotton, usually smiling or at ease. The message such images intended to convey was of a world where people knew where they belonged and were happy in their work. That image of the south stuck with Chloe throughout her life.

A hundred years later, we have the freedom and the responsibility to interpret images like these, and this letter that draws our attention to them, differently. Thanks to a wealth of scholarly and creative works which document the stubbornness of racism in American institutions–including for example Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, Carol Anderson’s White Rage and Ana DuVerney’s 13th, we can see more clearly the reality behind them and put them into context. Gilbert’s letter, penned by a Georgia veteran, contains virtually every element of Lost Cause ideology identified by historians writing since the 1960s. We can, for example, examine the words of the leaders of the Southern States on the eve of the Civil War, and acknowledge that they were not simply defending state rights but advocating for the further extension of slavery. In works like the 1999 book Without Sanctuary, we can readily access postcards of lynchings that circulated widely alongside the one W.H. Gilbert sent his grand-daughter Chloe. Lynchings increased in numbers in the 1890s, a horrific and direct means of enforcing what data-driven analysis of that period identifies as “an intricate and complex system of racial subordination”.

W.H. Gilbert’s postcard to Chloe was also part of that system. So too were public monuments that sprang up across the South in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the formation and spread of the Ku Klux Klan, and the continued display of the Confederate battle-flag, whether on display at my great grandfather’s grave in Albany, or on the shoulders of self-styled patriots inside the U.S. Capitol on January 6 2021.

When I shared with a colleague at the University of Helsinki my discovery of an enslaver in my own family tree, they responded by saying “so, I guess you’re going to cancel yourself.” I hope that they are wrong. What I hope instead is to prompt reflection on the legacies of the past. I believe that we best honor our ancestors’ voices by allowing them, and ourselves, the space to be wrong, and to aspire to a more just, equitable future. We stand a better chance of doing so by paying close attention to what they inherited, and what they–and we–choose to pass on.

References

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (2013) Americanah. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Allen, James (1999) Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America. Santa Fe: Twin Palms Press.

Anderson, Carol (2016) White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide. New York: Bloomsbury Books.

Du Bois, W. B. E. (1903/2007) The Souls of Black Folk. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DuVerney, Ava (2016) 13th. Kandoo FIlms.

Gallagher, Gary W. and Alan T. Nolan (2000) The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Hill, Benjamin Harvey (1867/1893) Notes on the Situation. In Hill, Benjamin H (Jr.) Senator Benjamin H. Hill: His Life, Speeches and Writings. Atlanta: T.H.P. Bloodworth.

Kersh, Roger (2001) Dreams of a More Perfect Union. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Stephens, Alexander (1868) A Constitutional View of the Late War between the States. Philadelphia: National Publishing Company.