By Kinga Połyńczuk-Alenius (HCAS Core Fellow)

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels

I initially became interested in conspiracy theories when studying a blog of a key Polish far-right activist in the context of my Collegium research on mediated racism in Poland. Although this activist first gained public prominence and recognition during the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ as one of the leaders of the anti-refugee movement, my analysis quickly revealed that the crux of his writing was, in fact, the elaboration of a multi-layered superconspiracy machinated by the Jews. While the timeworn leitmotiv of the Jewish cabal secretly orchestrating the course of history survives and thrives primarily – though not exclusively – in the anti-semitic far-right milieu, the current proliferation of spurious theories related to the Covid-19 pandemic lays bare the societal and political significance of conspiracy theories beyond the radical fringes. In Poland, for example, a recent survey has found that as many as 45 per cent of respondents agreed that ‘some foreign powers or countries are deliberately contributing to the spread of the coronavirus’, compared to 42 per cent who attributed the pandemic to ‘natural processes’.

With this in mind, it is as worthwhile to dispel conspiracy theories forcefully as it is to try and untangle their appeal.

Old explanations for a new situation

At the most basic level, a conspiracy theory refers to ‘the conviction that a secret, omnipotent individual or group covertly controls the political and social order or some part thereof’ (Fenster, 2008: 21). Although they might be based on kernels of truth, conspiracy theories exploit undisputable facts as a source material for questionable extrapolations. In other words, they are based on ‘the big leap from the undeniable to the unbelievable’ (Hofstadter, 1966: 38).

As a major part of the political and social (dis)order on a global scale, the ongoing pandemic has rapidly given rise to an impressive range of more or less half-baked conspiracy theories that seek to explain the situation. Symptomatically, many of them have latched onto the already existing explanations and implicated the usual scapegoats. Accordingly, it has been possible for politicians to tap into the seemingly bottomless deposit of antisemitism and represent novel coronavirus as a yet another Jewish plot to alter the world order, take control of sovereign countries and ‘neuter their populations’.

In a similar vein, White House officials have repeatedly intimated that the virus has been engineered in a Chinese lab, perhaps even as a biological weapon. This theory is a perfect illustration of a ‘curious leap of imagination’ that Hofstadter wrote about: it has been inferred from the Chinese government’s secrecy, the underestimation of the number of infections, and the underreporting of deaths. What makes this theory truly useful, though, is that it handily reinforces two anti-Chinese views at once: it confirms the malevolence and callousness of China’s pursuit of world dominance but also, through exposing the security compromises that enabled the virus to escape from the lab, it betrays characteristic Chinese incompetence.

The new villains: intangible, yet personified

More ‘grassroot’ conspiracy theories differ from those propagated by politicians in that in their search for an explanation they turn to the realm of the invisible and the intangible. In particular, the phony links between Covid-19 and technology and/or science seem to take centre stage.

In the technology department, the most popular conspiracy theory draws on 5G scaremongering. In this view, 5G technology weakens the immune system, rendering humans susceptible to viruses which, in turn, use the 5G network as a communication channel. The novel coronavirus is believed to have emerged in Wuhan because it was – counterfactually – the first city where 5G coverage was rolled out.

The next level of this conspiracy theory has been spun by the anti-vaccination movement, which eagerly combines scepticism towards (medical) science with mistrust of technology. The ‘vaccine hesitancy’ groups have piggybacked on the spurious connection between 5G and the novel coronavirus in the origin story that they have concocted for the Covid-19 pandemic. In that tale, the novel coronavirus is produced by 5G technology so as to warrant the creation of a bogus vaccine, intended not to cure the disease but rather to implant microchips through which humans could be remotely controlled.

At that stage, however, some questions still remained unanswered. Does 5G technology generate the virus autonomously? And who is supposed to take control of humanity once it has been microchipped?

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

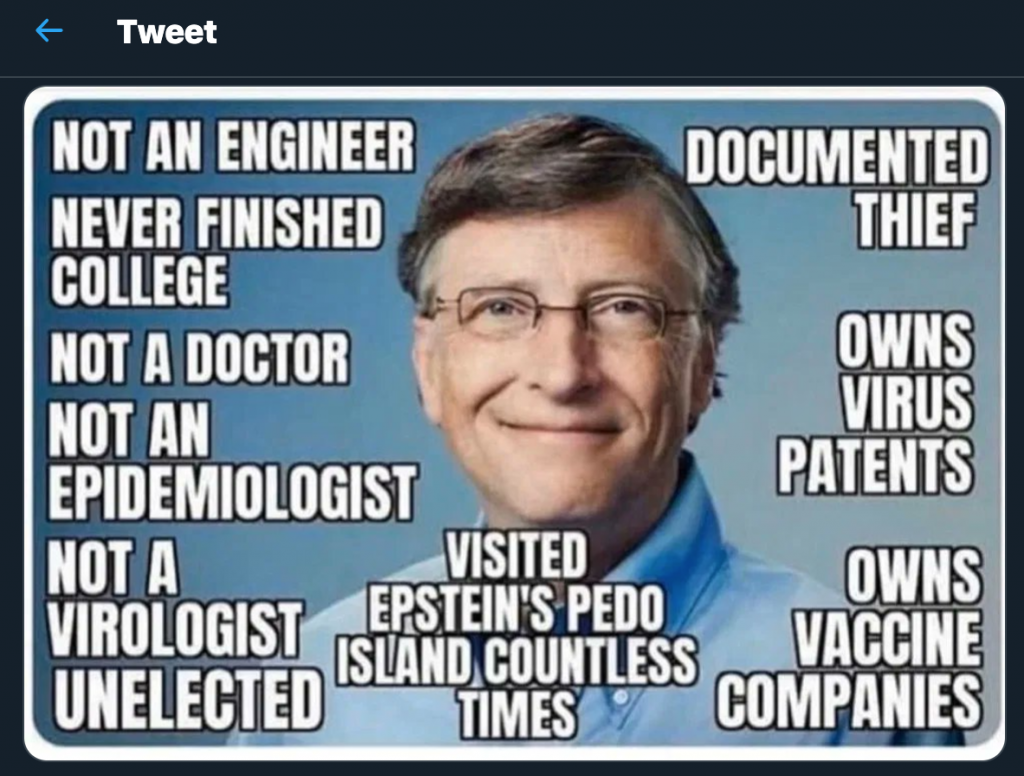

Any conspiracy theory becomes complete when the ultimate orchestrator is unmasked. And for Covid-19 pandemic, Bill Gates emerged as the grand operator. As a vocal critic of the Trump administration, a technological mogul turned philanthropist, a zealous proponent and generous funder of vaccine development, the Microsoft co-founder is the perfect scapegoat for a crisis that emerges on the intersection of technology and (medical) science.

According to this theory, the evidence of Gates’s culpability abounds. In a 2015 TED talk, he publicly and brazenly anticipated his evil plan by criticising and revealing the shortcomings of global pandemic preparedness. He has even had the audacity to cipher his evil plan in the official name of the disease: ‘COVID-19 (C)ertificate (O)f (V)accination (ID)entification – (1)=A (9)=I “Artificial Intelligence“.’ Already all-powerful, Gates is set to benefit from the pandemic, and the vaccine it brings about, in two ways: through garnering financial profit and enslaving humanity.

The discreet appeal of conspiracy theories

Predictably, the conspiracy theories related to the Covid-19 pandemic are based on evidence that is circumstantial at best and, more often than not, simply absurd. As such, they have been repeatedly debunked, declared a public health hazard, and ridiculed. Yet, the old plots still circulate, and the new ones continuously emerge, in social media and certain legacy media alike. We must then ask: what currency do conspiracy theories have in contemporary information-rich societies?

Crucially, not only are conspiracy theories a conviction or a set of beliefs, they also fulfil certain cognitive and psychological needs which are otherwise unmet in times of crisis.

Firstly, a conspiracy theory is a mode of cognitive mapping: an attempt to disentangle a complex situation through concocting a graspable, though not necessarily plausible or logical, explanation (Fenster, 2008; Jameson, 1988). Thus, the belief in conspiracy theory helps people to make sense of and navigate a confusing and inhospitable reality (Bale, 2007: 51).

In the case of Covid-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories provide complete, simple, seemingly rationalistic and watertight explanations. This is in stark contrast to the available scientific knowledge – complex, fragmented, changeable and contested – and to the actions of political decision-makers and state authorities, which appear haphazard and self-contradictory. Accepting that the pandemic has a singular cause (technological/military experiments), however absurd, might be more manageable than coming to terms with the complexity of the situation in which too many variables remain unknown.

Secondly, a conspiracy theory functions as a (maladaptive) coping mechanism. Under circumstances of social change, upheaval or crisis, conspiracy theories serve to grasp a rapidly unfolding situation that has a bearing on one’s life but is beyond individual control (van Prooijen and Douglas, 2017). To do that, such theories often rely on spurious new evidence to confirm what is already known, namely a superstition or a prejudice (Byford, 2011). By outsourcing blame onto the usual suspects, conspiracy theories enable people to rationalise, albeit in a way that does not stand to reason, their present difficulties (Bale, 2007). Accordingly, conspiracy theories provide a way for those who view themselves as innocent victims of the pandemic to explain their predicament as having a known, identifiable and evil source, be it the Jewish plot, Chinese incompetence, or Bill Gates’s machinations.

Thirdly, and relatedly, conspiracy theories are a paradoxical way partly to overcome the feeling of powerlessness (Bale, 2007). By denouncing culprits, individuals can reassert their own agency: while in the know, they are able to act on the previously incomprehensible and overpowering situation. If one believes that Bill Gates is single-handedly responsible for Covid-19 and the ensuing pandemic, taking to Instagram and bombarding Gates’s profile with accusatory messages might seem like a reasonable and potentially effective course of action.

Taking all the above into account, ad-hoc factual refutations and emotional dismissals might not do much to dispel the allure of conspiracy theories. In times of crisis, conspiracy theories will always be a step ahead of carefully crafted, evidence-based theories in providing an overarching, rationalistic, simple and, therefore, compelling explanation.

While I do not claim to have any practical pointers on how exactly to combat the adverse effects of conspiracy theories, it seems to me that a more effective way to do so would be to enable general public to accept, and cope with, the complexity and unpredictability of the world. Admittedly, this would require some sweeping changes in political communication, media crisis reporting as well as schooling and education, to name but a few examples.

Kinga Połyńczuk-Alenius (Photo by Tero Alenius)

References

Bale JM (2007) Political paranoia v political realism: On distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics. Patterns of Prejudice 41(1): 45-60.

Byford J (2011) Conspiracy Theories: A Critical Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fenster M (2008) Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture (2nd edition). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hofstadter R (1966) The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Jameson F (1988) Cognitive mapping. In C Nelson and L Grossberg (eds) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, pp. 347-357.

van Prooijen J-W and Douglas KM (2017). Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Memory Studies 10(3): 323-333.