By Anna Usacheva

Why are you a classical philologist?

Anna Usacheva

People often ask me what I do as a researcher. The questioner is clearly not interested in day-to-day practicalities: it is common knowledge that nowadays everybody from physicians to judges and football players to politicians spend as much time in front of their laptops as office workers. What the questioner really wants to know is why I spend so much time in front of my laptop reading or writing about thinkers or civilizations long obliterated from earth. Why don’t I devote my “screen-gazing” time to a more productive goal, such as comparing the number of likes given to one politician’s speech against those given to another, or to making and promoting culinary videos? The immediate benefit of these occupations is obvious and undeniable, while showing what is essentially useful in studying the lives and ideas of people who lived more than a millennium before us – this is a more formidable task. In what way can the experience of these people be relevant to our modern-day lives? And is there any real possibility of accurately interpreting this experience, given that their living conditions were so different from ours that even armed with the richest grammatical expertise in ancient languages we may fail to grasp the sense of some short casual letter inscribed on a piece of papyrus?

To this question one often hears the following response: Despite all the cultural differences which separate our age from the ancient civilizations, certain primordial and archetypal, or simply conventional, similarities nevertheless exist between our cultures, which may enable us to discover some useful information (like a recipe for some strong aphrodisiac) or entitle us to happily admit that “They were so clever that they even used bathrooms and plumbing systems as we do!” Though I do not deny an element of truth to this position, I don’t think it does full justice to either ancient civilizations or contemporary scholarship. I believe that our desire to study ancient cultures is due not to some sort of similarity between them and contemporary culture, but rather to the apparent difference between the two. Scholars may be mildly surprised when they start investigating the life of Roman citizens, but as they go further in their study, they are often astonished to discover the prosperity, intellectual and cultural achievements, and general self-satisfaction which many of the past societies enjoyed in spite of the defects of their medical care or transport systems. This fact suggests that our contemporary civilization has not discovered a universal theory of how to procure people’s happiness which would entitle us to look at previous civilizations as at infusoria under a microscope. We do not have the right to suggest that we know the correct method of reading “the book of human history” written on the scraps of papyri, manuscript pages or preserved in archeological finds.

To this question one often hears the following response: Despite all the cultural differences which separate our age from the ancient civilizations, certain primordial and archetypal, or simply conventional, similarities nevertheless exist between our cultures, which may enable us to discover some useful information (like a recipe for some strong aphrodisiac) or entitle us to happily admit that “They were so clever that they even used bathrooms and plumbing systems as we do!” Though I do not deny an element of truth to this position, I don’t think it does full justice to either ancient civilizations or contemporary scholarship. I believe that our desire to study ancient cultures is due not to some sort of similarity between them and contemporary culture, but rather to the apparent difference between the two. Scholars may be mildly surprised when they start investigating the life of Roman citizens, but as they go further in their study, they are often astonished to discover the prosperity, intellectual and cultural achievements, and general self-satisfaction which many of the past societies enjoyed in spite of the defects of their medical care or transport systems. This fact suggests that our contemporary civilization has not discovered a universal theory of how to procure people’s happiness which would entitle us to look at previous civilizations as at infusoria under a microscope. We do not have the right to suggest that we know the correct method of reading “the book of human history” written on the scraps of papyri, manuscript pages or preserved in archeological finds.

How does one read “the book of the past”?

However, what seems to me to be rather inspiring in this status quo is that in our perception all the textual and material data that we have represent a continuum of the texts and stories in the book of our past. Versatile and miscellaneous as they are, these texts and stories have worked their way into the same leathery binding of human history, which will incorporate the texts and stories of our generation just as casually as it did with the opera of our ancestors.This simple fact allows us to cultivate in ourselves a healthy humility, which can prevent us from two misleading and, unfortunately, rather popular approaches to the research. The first consists of claiming that we can perfectly understand the texts of the past without bothering to study the historical context and original language of these texts, because there is no essential difference between the past and the present. The second approach exaggerates the gap between various historical epochs to the extent that renders it useless to make any inquiry into historical material because its meaning is unfathomable to us.

In my opinion, to find the middle way between these extremes, we should follow the “spirit of intertextuality”, which allows us to see the intertextual connections between the past and the present, the connections which neither blur nor exaggerate the distinctions between the texts and stories of different epochs. Belonging to our generation, we at the same time are the authors and the heroes of our stories as well as the readers of the texts of the past. To navigate in this stream of syllables and meanings, we should remember that the texts of the present are different from the texts of the past and that together they form a unique continuum of human history. In such a way, the all-embracing spirit of intertextuality binds and sews together various disciplines and attaches to them a particular anthropological strand. Whether written a millennium or a second ago, every story in the book of the past concerns human beings. Whatever the initial goals and aspirations of various disciplines may be, they all pursue their long and glorious journey through the universe, just as light travels to the earth unobstructed for nearly 93 million miles and emphatically a few feet above the ground it stumbles upon man and becomes a human shadow.

Different times – different horizons

An example of this situation can be easily found in my own research project entitled “Physiology of Human Cognition in the Scientific, Theological and Monastic Contexts of Late Antiquity”. If I were to advocate the necessity and actuality of this study, I could speak about the fascinating brain mapping theory, found in the late antique treatise On the Nature of Man, which I am going to study. Although historians of medicine have recognized that this work contains the first evidence of the theory of the ventricular localization of various physiological functions in the human brain, so far nobody has really explained how this theory could have been formulated without fMRI machines and in circumstances where medical scholars were not even permitted to dissect a human body. Captivating in its own way, this is not the chief interest of my research, because I marvel not at vague and illusive similarities between ancient and contemporary medical theories but at the apparent contrast between the scientific methodological approaches of late antiquity and those of contemporary science. The author of the treatise I study saw no fault in combining the most progressive medical theories of his time with the philosophical and theological concepts of his and previous periods. Thus, he even claimed an analogy between human and divine natures, and in building his theological theory, he heavily relied on the treatises of famous Greek physicians.

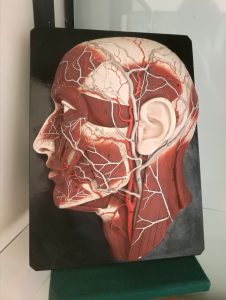

Anatomical face, Leipzig, late 19th century

I find it difficult to imagine a contemporary priest using an anatomical or pharmacological textbook in his or her preaching along with (or even more extensively than) the Bible. We all used to believe that a reasonable gap between science and humanities should be preserved in order to prevent our civilization from falling into “the chaotic alchemical obscurity of the Middle Ages”. While solid and legitimate in its own way, this methodological principle cast a shadow on the collaboration between the sciences and humanities, which meant that many of the brilliant theories which were successfully deduced from experience failed to find their way back into the life of people. The peculiar skill of combining these branches of human knowledge exemplifies one of the differences between contemporary and late antique societies. This fact inspired me to study and learn from the experience of conducting interdisciplinary research in the past.

Questions for the sake of questioning

Different disciplines complement each other not only because a historian may one day discover that their curiosity concerning ancient numerical systems has something of the rigorous interest of a contemporary mathematician, but because both scholars may be startled at recognizing various ways of looking at such a regular and stable phenomenon as a number. Understood in a broad sense, intertextuality is an integral part of successful research, not so much because somebody can reasonably hope that all the numerous aspects of phenomena can be identified and a comprehensive explanation of them provided. To expect and strive for this result would be equal to voluntary (though perhaps unconscious) suicide, because for all the mysteries surrounding the human mind, one thing is more or less clear – it lives as long as it runs and runs as long as it lives. Therefore, there should and, hopefully, will always appear many more questions and fascinating strands to long-recognized and abundantly discussed problems. Eventually, a very practical and obvious effect of this everlasting scholarly thirst is that every generation has the right to discover our universe for the first time and to make it a comfortable and even more beautiful place for us. And this goal can be achieved only if we understand those people whose comfort and well-being we enthusiastically promote. To understand ourselves, we need to compare our society with a different one, which may well be one that lived more than a millennium before us.

Anna Usacheva has been working as a Core Fellow at the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies since September 2018. Her research project focuses on the physiology of human cognition in the scientific, theological and monastic contexts of late antiquity.