By Lilian O’Brien, Walter Rech, and Svetlana Vetchinnikova

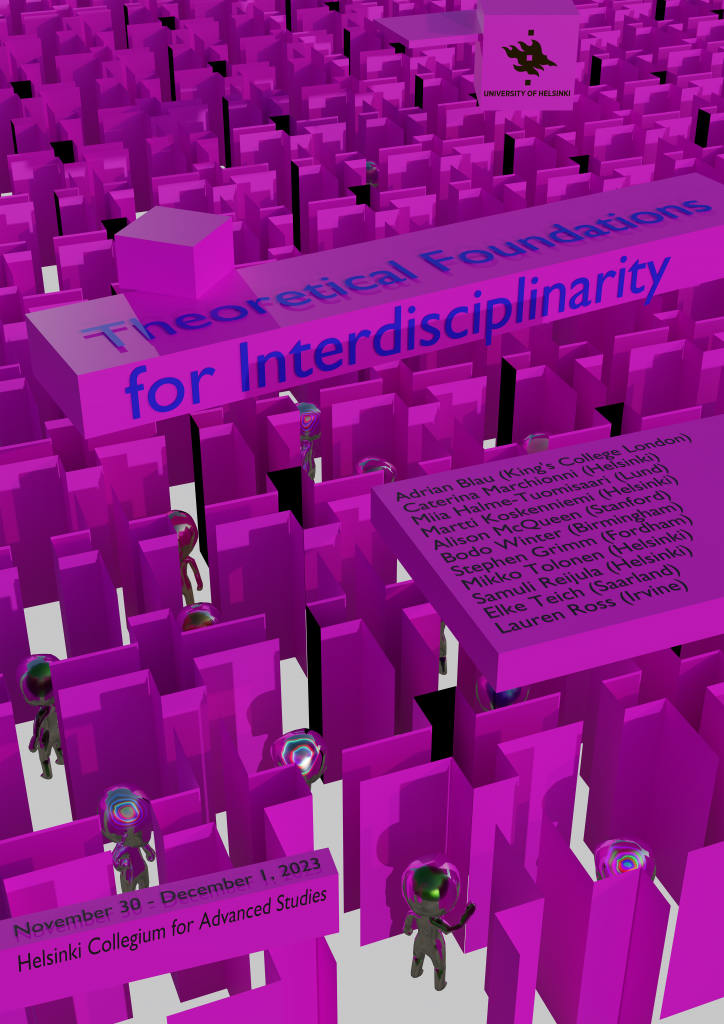

The authors of this post reflect on the outcome of the symposium Theoretical Foundations for Interdisciplinarity, which they conceived together while working as core fellows at the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies. The symposium took place at HCAS on 30.11.–1.12.2023.

Interdisciplinary research has yielded many new insights and methodologies. It allows us to tackle multi-faceted problems that draw from different domains of expertise.

But many who engage in interdisciplinary research will tell you that it can be difficult to do. Our symposium aimed to shed light on key sources of difficulty. Philosophers, linguists, and intellectual historians from Finland, Germany, Sweden, the UK, and the USA, came together for two days of rich discussion in November and December.

Image by Pavel Kaltygin

As the name of our symposium suggested, our interests were “foundational”. We were not, that is, primarily concerned with difficulties encountered in specific instances of interdisciplinary research, but with broader themes that are relevant to most interdisciplinary research.

For example, are there different kinds of explanation being sought in, say, the humanities and social sciences? We were also concerned with how variations in how language is used in different disciplines may prevent mutual understanding. Does our shared human cognitive architecture help or hinder interdisciplinary work? Given that concepts evolve over time, and shape our disciplines in deep ways, how does this affect our interdisciplinary work?

The papers at the symposium provided a rich and rewarding conversation. Here we would like to share brief observations of each of the co-organizers of the workshop.

Walter Rech:

The symposium illustrated that the dynamics of scientific evolution are both disciplinary and interdisciplinary, micro and macro. Historically, moves towards specialization as well as cross-fertilization have generated a productive tension.

Martti Koskenniemi noted that specific disciplines tend to produce and perpetuate their own worldview as characterized by particular interests and mindsets, thereby preventing a meta-description of the world. At the same time, some disciplines or sub-disciplines may move towards convergence or retain certain traits that they share with neighboring fields. Within the humanities, for instance, intellectual history remains a typical blend of history and philosophy: it discusses historical sources by simultaneously providing relevant historical contexts and delving into the philosophical analyses of texts, as Adrian Blau argued.

New technologies may also encourage interdisciplinary work. There is increasing convergence, for instance, between classical intellectual history and the digital humanities. Alison McQueen and Mikko Tolonen stressed the centrality of digital methods for expanding historical knowledge and analyzing large bodies of sources in a systematic manner. Within critical history, digital humanities may broaden existing canons and help make visible certain aspects of the past that have remained invisible so far.

Certain disciplines today appear as inherently interdisciplinary and can hardly be imagined otherwise. This is the case of human rights, as Miia Halme-Tuomisaari showed. While early human rights scholarship focused on human rights norms from a largely legal perspective, the broader phenomenon of human rights politics, diplomacy and culture is now studied by social and political scientists, historians, philosophers and economists. Importantly, these perspectives do not produce a meta-description of human rights but rather contribute to a more comprehensive picture of the overarching field, thereby also increasing awareness of the challenges facing human rights today.

Svetlana Vetchinnikova:

In the efforts to understand another discipline, it is useful to keep in mind that, in a way, any discipline is a product of cultural evolution. Disciplines evolve in social interaction between community members and are therefore subject to the influence of social, cognitive, and linguistic factors. As a result, disciplinary state-of-the-art may reflect the origin and historical development of the field no less than its actual subject matter. Any discipline as we know it could have been different. We do what we do because of how we got here.

This is not a fundamental flaw. In fact, complex systems, that is, open systems where multiple agents interact over time, such as all biological systems, produce optimal results through self-organization, adaptation, and evolution. However, our understanding of a field is incomplete without an appreciation of its history.

For example, statistics is often seen as the epitome of objectivity in science. This does not hold, as Bodo Winter vividly demonstrated. Rather, it emerged in the interplay between the processes characteristic of human social interaction like any other discipline. The spread of significance testing, which is arguably the most widely used statistical framework today, can be traced back to the specific sociopolitical context within which it developed including the idea of eugenics, the level of technological development of the time, the incentive system of academia with its focus on publishing as well as the bandwagon effect.

In appreciation of such developments, we may hear, especially perhaps from academic administrators, that we need to shake up the fossilized structures of academia. Indeed, some of the fossilized structures may be artifacts of the historical processes and can create perverse incentives and unintended consequences. At the same time, a so-called “fossilized structure” is an ultimate form of efficiency.

Fossilization, routinization, and conventionalization all refer to the same process of learning through practice. A convention, whether it is a linguistic form-meaning pairing, a social practice, or a methodological procedure, is a low entropy zone with reduced information load which lets us function efficiently. It is not just a highly automatized process like brushing your teeth but also a socially accepted process like agreeing with each other on a specific way of brushing your teeth to achieve predictability – which of course would be entirely useless in the case of teeth brushing but essential, say, in language.

There is a catch though. A convention reduces information load and facilitates communication for the members of the community who agreed on it, but not for the outsiders. So something which makes our work efficient within a field at the same time creates barriers between fields. The principle applies to all social practices including language. As Elke Teich showed, increasing conventionalization of a disciplinary sublanguage reduces cognitive load and makes communication efficient within a discipline but at the same time hinders interdisciplinarity.

In sum, historical baggage is both a blessing and a curse. It may help to unpack it now and then.

Lilian O’Brien:

Consider a cell biologist and a historian. They would seem to have little in common. The cell biologist is curious about what cells are, what their parts do, and what causal role they play in an organ. The historian is, say, interested in the rise of an empire, what sustained it, and what led to its demise.

And yet, in spite of the differences, central to the curiosity of both is the desire to understand how one thing causes or sustains the operations of another. How do mitochondria allow the cell to sustain its operations? How did a trade route sustain the operations of an empire?

Stephen Grimm’s talk emphasized such commonalities – he argued that a close study of research in fields as diverse as history and musicology reveals deep commonalities in the kind of understanding that is sought. In Lauren Ross’s talk, we learned about different kinds of causal concept, such as pathways and cascades. These show up in disciplines as diverse as sociology, chemistry, and environmental science and reveal common explanatory strategies. They also highlight ways in which diverse disciplines could be fruitfully brought together.

This is not to flatten out the many differences among disciplines, to pretend they are not there. As was amply illustrated in Caterina Marchionni’s talk, to insist upon harmony among disciplines even when they share the same object of curiosity – mental health in humans – is a mistake. It is not possible to integrate all of the important insights from diverse fields into a single overarching framework.

And, of course, the cell biologist seeks causal regularities, repeating patterns in nature. They wish to understand why things always happen in the cell in a particular way. By contrast, the historian’s interests are not usually quite so general, but seek understanding of a particular moment or sequence of events.

These and other differences speak against the assumption that we can do away entirely with disciplinary boundaries and diverse methods. But acknowledging this allows us to highlight the value of diverse disciplines, diverse methods, and to steer us clear of discounting one discipline in favour of another.

The symposium gave us an extremely valuable opportunity to stand back from the disciplines, to reflect upon and articulate important commonalities and differences among them. In doing so, we become better prepared to note both opportunities for, and obstacles to, interdisciplinary work.