By Ilkka Lindstedt

UPDATED January 7, 2014.

In May–June 2013, me and photographer Hannu Aukia conducted epigraphic studies in the modern-day Jordan. The expedition was funded by the Finnish Institute in the Middle East and IHANE. We documented a handful of Ancient North Arabian (from roughly the 6th century BCE to the 6th century CE) and Nabataean as well as some early Arabic (7th–9th century CE) inscriptions and graffiti. These can be found, for instance, in ruins of Roman and Umayyad era castles, palaces, and caravanserai. The pictures, of which here only a handful will be included, can be seen online at http://www.flickr.com/photos/97275038@N06/sets/. Please note that the online database is still very much a work-in-progress.

We visited the following sites: Qasr Kharana, Qasr Uwaynid, Qusayr Amra, Qasr al-Hallabat, Hammam al-Sarakh, Qasr al-Azraq, Qasr al-Tuba, Wadi Rum, Petra, Khirbat al-Askar, Qasr al-Bashir, Wadi Mujib, Qasr al-Mushaysh, and Qasr al-Mushash (two different localities, al-Mushaysh being near the town of Karak, al-Mushash near Amman).

Here I will discuss three sites. First, Qasr Kharana, perhaps an Umayyad era building. Second, Qasr al-Mushaysh, perhaps a Roman era site, with underground dwellings. And third, Wadi Mujib, a valley containing hundreds of North Arabian graffiti and drawings.

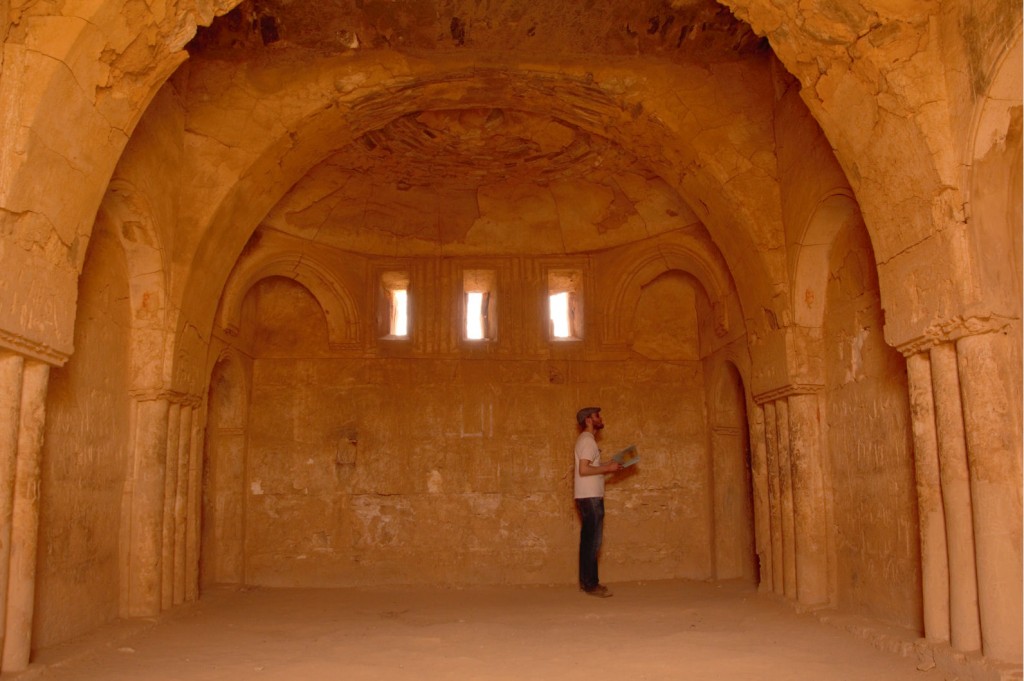

Qasr Kharana, a very well preserved Umayyad era (661–750 CE) building. Although it looks like a castle for military use, it never served that purpose. What look like arrow-slits are actually ventilation holes, according to Stephen K. Urice.

Stephen K. Urice, in his “Qasr Kharana in the Transjordan” (Durham, 1987), dates the Qasr Kharana to the late seventh century CE. This is done by archeological, architectural, and circumstantial evidence. We managed to found two new early (seventh–ninth century) Arabic inscriptions. The Arabic inscriptions and graffiti will be published in the journal Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy.

[The above section has been updated, with significant changes.]

One of the very interesting, and little, if at all, researched places was Qasr al-Mushaysh, about 50 km south-east of the town of Karak. Heavy mining activity was taking place near the ruins. Some kilometers away, we heard, and saw, many explosions. It is worryingly possible that the ruins of Qasr al-Mushaysh won’t be there after some years.

Qasr al-Mushaysh contained ruins of many different buildings, perhaps originally from the Roman era. There were also many underground dwellings. At the site, there was two Nabataean Aramaic and some early Arabic inscriptions.

We surveyed two underground dwellings which were, however, inaccessible because of sand gathered at the bottom.

![An Arabic invocative graffito, in Kufic script (seventh–ninth century CE), found at Qasr al-Mushaysh. Note, at the top left, a picture of a camel, which might or might not be drawn by the writer of the graffito. Proposed reading: In the name of [God] O God! [Pardon] Abd Allah bn (… an unclear name) (two indecipherable lines) Amen, [Lord] of the World!](https://blogs.helsinki.fi/ihane-blog/files/2013/06/2013-06-02-13.23.46-768x1024.jpg)

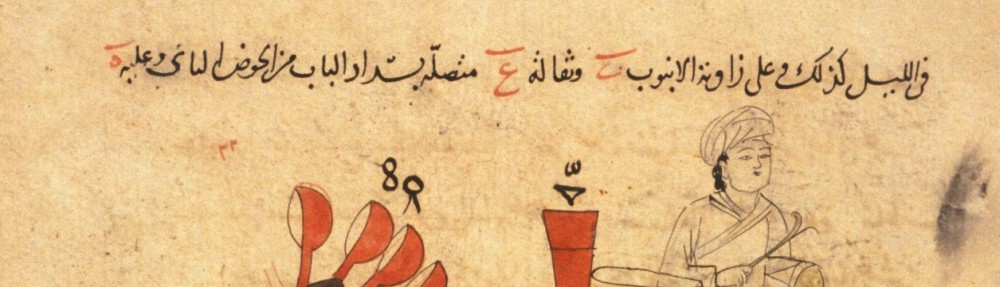

An Arabic invocative graffito, in Kufic script (seventh–ninth century CE), found at Qasr al-Mushaysh. Note, at the top left, a picture of a camel, which might or might not be drawn by the writer of the graffito. Proposed reading:

In the name of [God]

O God! [Pardon] Abd

Allah bn Hammad and

his parents and their offspring.

Amen, [Lord] of the World!

through a rather badly-maintained dirt road, which seemed, at times, rather dangerous.

The real treasure awaits the explorer at the bottom of the valley, where basalt stones start to appear. These stones contain hundreds of drawings (usually animals). We also found, in addition to many modern Arabic graffiti, one invocative Kufic (i.e., early Islamic) inscription.

Basalt stone is especially good for inscriptions, because it is easy to carve and it weathers centuries without any erosion on its surface.

The purpose of our expedition was to document Ancient North Arabian and early Classical Arabic inscriptions and graffiti in situ. These can be accessed online at http://www.flickr.com/photos/97275038@N06/sets/.

Mr. Ilkka Lindstedt

MA, PhD (as of Jan. 21, 2014), Arabic and Islamic studies

Intellectual Heritage of the Ancient Near East project

University of Helsinki